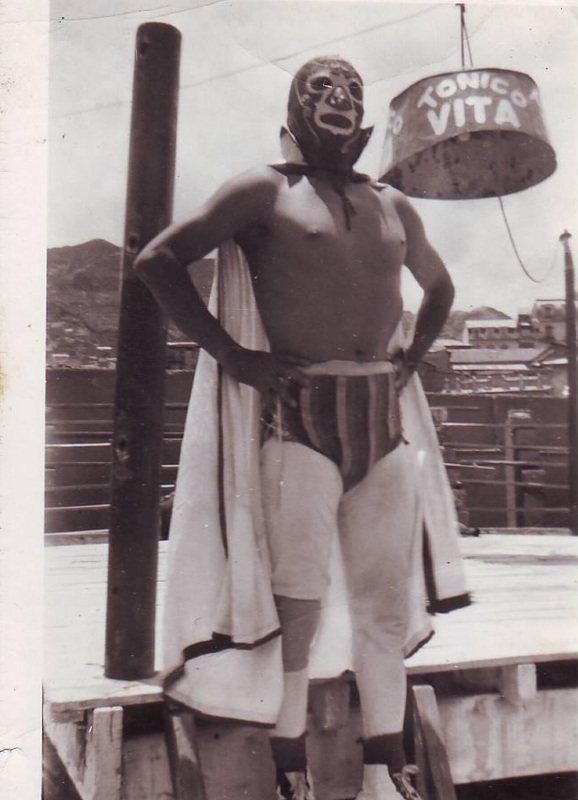

These experiences were in part because I was doing research in a male-dominated social setting. Indeed, in many ways, they served to inform my analyses of what Bolivian women might experience in their own involvement in wrestling. Of course my gringa-ness, foreignness, and lack of familial ties to anyone in the group make my situation slightly different. But these instances still tell us something about gender relations within the context.

But these experiences are not related just to my subject matter. In my current research, I have to be wary, not only of walking alone at night in Alto Hospicio, but also of the advances of police officers and public city officials when they send me non-work related Whatsapp messages. I have spoken with countless women about their similar experiences, one of whom was even evicted from her apartment in her fieldsite in a small conservative Middle Eastern area after refusing the advances of her landlord.

To say that these experiences are frustrating is an understatement. They are not just an annoyance of daily life, but they profoundly impact one’s ability to do research, and maintain community ties. In just three short days it will be the two-year anniversary of the day I finished fieldwork. Yet I still feel the effects of these types of gendered relations.

Today I received a facebook message from one of the more senior and well respected luchadores in La Paz. At first I was flattered to receive a message because he asked when I will be wrestling again. “Quiero venir a verte” [I want to come watch you]. But the conversation quickly turned

Nell: No, I don’t have a husband. And unfortunately I don’t know when I will wrestle again.

Luchador: Oh, then he’s your friend with benefits? That’s what he told me.

[unclear if he’s referring to ‘friend with benefits’ or marriage]

Nell: Um, no. We don’t know each other well, so I don’t feel comfortable commenting on my private life with you.

Luchador: Yes, I know you. You’re the gringuita.

Nell: Yes, of course, but we are not friends. I’m not sure why it matters to you and I find it disrespectful.

Luchador: Sorry. Bye.

And with that I most likely lost an important contact. Of course, I’m in a better position now, because my fieldwork is finished, some of it is published, and I’ve moved on to a new project. But I’m stuck now in a position of whether I even mention this to Jorge*, my former wrestling partner, and a fairly good friend. Do I continue as a friend always wondering if he is telling others that I am something of a significant other or sexual plaything to him? Do I mention it to him and confront the problem head on, most likely with little benefit either personally or professionally? Or do I assume what this older luchador said to be correct and silently stop being his friend.

I realize this is the type of problem many anthropologists face, regardless of gender, regardless of region, and regardless of topic. But as I recently wrote about the perception of women anthropologists flirting, extroverted actions of men are interpreted differently than those by women. This is something that will not be “solved” easily, particularly when we consider that many times this happens in places where there is less awareness of “rape culture,” less ability for women to participate in social life, and more complicated relationships between race, class, cosmopolitanism, and locality. I do intend to keep up a conversation about it though.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed