Today, there are four major wrestling organizations currently operating in La Paz: LIDER (Luchadores Independientes de Enorme Riesgo), LFX (Lucha Fuerza Extrema), Super Catch, and Titanes del Ring. LIDER, LFX, and Super Catch are smaller than Titanes del Ring, and only Titanes and LIDER have permanent places of performance. These two groups host foreign tourists in their El Alto performance venues each week, though Titanes del Ring boasts a much larger crowd and much larger group of travelers than LIDER. Super Catch usually produces shows in neighborhoods such as Villa Victoria (nicknamed Villa Balazos because of the frequency of shootings in the area), Villa Copacabana, or Villa Armonía—all working class neighborhoods of La Paz. However their schedule is somewhat sporadic. They have also recently opened a training program for young wrestlers that remains small. LFX is the smallest and least known of the operations with rare performances. Titanes del Ring, conversely, consistently attracts hundreds of audience members each Sunday at their show in the Multifuncional de la Ceja de El Alto (the multifunctional arena located in the Ceja market area of El Alto).

|

I was contacted late last week by a reporter for a well-respected British news outlet. He is writing a story on the cholitas luchadoras (which as I side note I'm intrigued by, because there is definitely an article from this same source for a few years ago I've referenced a few times). He asked questions on several topics, including the history of lucha libre in Bolivia. This is something about which I have found very little authoritative information. After many conflicting interviews and hours of pouring over Bolivian newspapers from the 1950s-1970s both here and in the US Library of Congress, here is what I know. You can find recent history here, and history of Bolivian lucha libre in the 1970s-1980s here. Though almost every veteran luchador in Bolivia tells the story a little differently, it was during the time of nationalism in the decade following the 1952 Revolution that lucha libre made its first appearance in Bolivia. The form of wrestling that developed in Bolivia already had a long history. Charles Wilson (1959) has traced exhibition wrestling to army men in Vermont in the early 19th century. During the civil war organized bouts became popular among Union troops. After the war, saloons in New York City began promoting matches to draw customers. By the end of the 19th century PT Barnum was using wrestling “spectaculars” in his circus. At first, wrestlers would fight untrained “marks” from the audience, but by the 1890s they began to fight trained wrestlers planted in the audience. It was then that it changed from a “contest” to a “representation of a contest.” These spectaculars were very popular and were replicated at county fairs, which eventually resulted in intercity circuits by 1908 (Wilson 1959). By the 1920s, promoters began to add gimmicks to make characters more memorable. In 1933, after character development, rules, and other conventions had been established, a promoter named Salvador Lutteroth brought exhibition wrestling to Mexico. He and his partner Francisco Ahumado set up their first wrestling event in Arena Nacional in Mexico City on September 21, 1933. The next year they began the Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre (Levi 2008:22). In the next few years, innovations in costuming, character, and technique further “Mexicanized” the genre. Levi argues that at this time the audience was likely made up of both popular classes as well as elites (2008:23). By the 1940s, lucha libre spectators were more from the popular classes, but it still retained a sense of urbanism and modernity (2008:23). In the 1950s, it began to attract a middle class audience on television, but it only remained broadcast for a few years. It was also during this time that it became a popular subject for hundreds of Mexican films (2008:23). During this era, exhibition wrestling arrived in Bolivia. Most wrestlers suggest that lucha libre was first performed in Bolivia sometime between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s, as Mexican wrestlers traveled to South America, performing and then training the first generation of Bolivian luchadores. Many of the most veteran Bolivian wrestlers who are still active in lucha libre identify these Mexican luchadores as their childhood inspiration. Rocky Aliaga, a Bolivian who currently wrestles in Spain told reporter Marizela Vazquez, “From my childhood I was fan of wrestling and what excited me most was to attend events…of Mexican characters such as Huracán Ramirez, Rayo de Jalisco, and Lizmark.” In particular, Huracán Ramirez is often mentioned as one of the most important influences. Mr. Atlas, a veteran La Paz wrestler recalls, "I started fighting when I was 13 in 1965, when the greats of Mexican wrestling arrived in La Paz. Particularly I remember Huracán Ramirez, the man who fathered me." An interview with Boliviana Euly Fernandez, the widow Huracán Ramírez Younger wrestlers, like Anarquista from Santa Cruz, also note that the reputation of lucha libre in neighboring Perú was important to the formation and popularity of Bolivian wrestling. Mexican wrestlers toured South America, but it was the periodic visits by Peruvian wrestlers to La Paz that gained a hold in the 1960s. (7-23-2011).

Today, there are four major wrestling organizations currently operating in La Paz: LIDER (Luchadores Independientes de Enorme Riesgo), LFX (Lucha Fuerza Extrema), Super Catch, and Titanes del Ring. LIDER, LFX, and Super Catch are smaller than Titanes del Ring, and only Titanes and LIDER have permanent places of performance. These two groups host foreign tourists in their El Alto performance venues each week, though Titanes del Ring boasts a much larger crowd and much larger group of travelers than LIDER. Super Catch usually produces shows in neighborhoods such as Villa Victoria (nicknamed Villa Balazos because of the frequency of shootings in the area), Villa Copacabana, or Villa Armonía—all working class neighborhoods of La Paz. However their schedule is somewhat sporadic. They have also recently opened a training program for young wrestlers that remains small. LFX is the smallest and least known of the operations with rare performances. Titanes del Ring, conversely, consistently attracts hundreds of audience members each Sunday at their show in the Multifuncional de la Ceja de El Alto (the multifunctional arena located in the Ceja market area of El Alto).

0 Comments

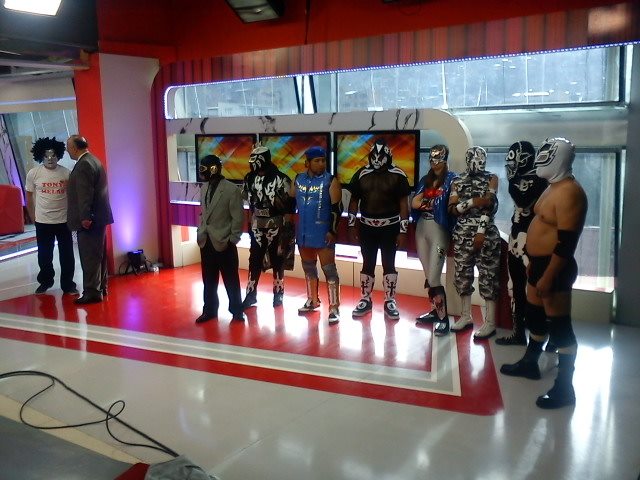

My favorite example of the ironic appreciation of lucha libre, which I saw live on Friday night, is the band Surfin Wagner. I first heard of them because the lead singer was a friend of a friend, but quickly discovered they had quite a following of Paceños. The band’s name is derived from a famous Mexican luchador, Dr. Wagner, otherwise known as Manuel González Rivera. He began wrestling in the 1960s as a rudo, but by the early 1980s—when the members of Surfin Wagner and my friends were young children—he had become a technico. In 1985 he lost his match in a well-publicized event and essentially retired. The band, like my friends who I wrote about here, creates humor using a frame shifting strategy by combining lucha libre aesthetics with surf music. The band members use lucha libre inspired names (Pedro Wagner, Médiko Loko—a misspelling of famous Mexican luchador Médico Loco, Roy Fucker—after a Japanese anime character later used in Mexican wrestling, El Momia, and Comando—both popular characters in Bolivian wrestling), and wear lucha libre head-masks along with their Hawai'ian print shirts. They describe their music as “el Garage, el punk y principalmente el Surf, siempre con un toque de sátira e ironía” [garage rock, punk, and principally surf, always with a touch of satire and irony]. The “biography” of the band on their website suggests that the band members are legitimate luchadores (again with irony), and they point out the incongruity of a surf band in a country without access to the sea. Clearly their use of the lucha libre aesthetic is meant to evoke laughter rather than contribute to a serious musical appreciation. So, over these last three posts, I've tried to give a sense that for many Paceños lucha libre in general, and the cholitas luchadoras’ participation specifically, are a light-hearted representation of Latin American culture. In a sense, lucha libre is positioned as authentically Latin American in a now-globalized world. As they combine cholas with punk culture or classic Mexican luchadores with surf rock, they reterritorialize these “traditional” icons by merging them with global symbols. When Super Catch wrestlers made appearances on morning and evening national talk shows, another kind of irony was present. Granted, Latin American talk show hosts are not known for being subtle, but the overacted excitement, fear, and horror these hosts communicated verged on the clowning Edgar was always so adamantly against. When Super Catch wrestlers made appearances on morning and evening national talk shows, another kind of irony was present. Granted, Latin American talk show hosts are not known for being subtle, but the overacted excitement, fear, and horror these hosts communicated verged on the clowning Edgar was always so adamantly against. In March and April of this year, Super Catch luchadores (including myself) appeared on the Univision morning program, Revista, five times. Though the show has four hosts, it was always Tony Melo who interviewed us, and sometimes even donned a luchador mask acting as a mark for the luchadores. The segment always featured a brawl between wrestlers, and often Tony would be pulled into the grappling. The peleas always ended with Super Catch luchadores ganging up on Tony, as he was flung around the sound stage and mock kicked after being thrown to the floor. He very much acted as the clown figure in these situations, flailing arms, and making exaggerated faces for the camera. He always wore a curly wig, and t-shirt that said “Soy No. 1.” Tony Melo is on the far right with his co-anchor. Super Catch luchadores are: Super Cuate, Big Boy, Desertor, Black Spyder, Lady Blade, Tony Montana, Gran Mortis, and Big Man In contrast, the luchadores seemed more serious. Our costumes were clearly better constructed. Our moves were more practiced and more effective in contrast to Tony’s. But much like Edgar’s worries about the cholitas luchadoras, Tony’s clownish acting gave an air of farce to the wrestling that happened on television. No luchadores ever commented on this except to roll their eyes occasionally when Tony was mentioned in the backstage area. Nor did I have a chance to ask Tony or the program producers what their intentions were with the way they presented lucha libre. But the audience for Revista is much larger and far more varied than the in-person audiences which actually attend events. There were viewers that phoned in to win free entry to the event, often saying they hailed from working class neighborhoods like Villa Armonía in La Paz or Villa Esperanza in El Alto. But this is also a television program which professional Paceños watch as they prepare in the morning for work as managers in banks, universities, and international organizations. Thus, the fact that Tony’s acting on the program reflects the ironic appreciation of lucha libre is not surprising. Though TV interviewers always treated all the luchadores with respect, their over-acted treatment of the segments seemed to stem not only from their television personalities, but from a deeper sense of irony they were communicating to viewers.

One of the peer reviewers for my JLACA article suggested that I include more information about what “elite” Paceños think of lucha libre. I didn’t think this fit well into the article, but I do think the general public’s reactions to lucha libre are something interesting to be considered. This is part one of a short series on middle class interpretations of lucha libre. The luchadoras are “un orgullo Paceño en La Paz y El Alto” [A Paceño pride in La Paz and El Alto] David, a local LGBT activist told me. “Es una pasion de multitudes…la gente burguesa y popular” [It’s a passion of the multitudes. The elite and popular classes]. It was not exactly my experience that they were the “passion” of middle class people, but they were certainly within the realm of popular discussion topic. As I wrote about here, one night at a party I put on a pollera and braided my hair. Gonz was the only one there who knew my secret, so when Luis, shouted “Tienes que luchar! Como las cholitas en la lucha libre” I was caught off guard. Amidst much laughter we all started pretending to wrestle. To my friends at the party, the luchadoras are something of a joke that carries classed inflection. Like a monster truck rally or square dance might be viewed by urban elites in the United States, lucha libre is not disparaged outright, but seen with a certain sense of dismissal or ironic appreciation. Here they express an understanding of the preference for the genres of excess that has often been classed. As Linda Williams explains of film genres, those that have a particularly low cultural status—horror, pornography, and melodrama—are ones in which “the body of the spectator is caught up in an almost involuntary mimicry of the emotion or sensation of the body on the screen” (1991:4). These films, rather than appealing to elite classes as “high art” are seen to be for the less educated, less “cultured” masses. A luchador's son performs as "Chucky" at the 30 March 2012 Super Catch Event And indeed, lucha libre combines aspects of all three of these film types. The enacted violence of the ring reflects the gratuitous violence of horror films. The intimate contact of bodies, and sometimes explicit sexually charged scenarios can be read as pornographic (see Messner, et. al 2003, Rahilly 2005). And several scholars have pointed to the melodramatic nature of the extreme good and evil portrayed in exhibition wrestling (Jenkins 2007, Levi 2008). Thus, for many of my friends lucha libre lies squarely within the bounds of that which is not to be appreciated—at least on an artistic or serious level. However, like North American young people, young Paceños sometimes have ironic appreciation for degraded cultural symbols like lucha libre. Irony often functions as a “frame shifting” mechanism (Coulson 2001) in order to express humor. When I entered the party wearing a pollera, Gonz shouting “cholita punk” shifted the frame from the representation of cholitas as traditional and thoroughly Bolivian icons, to something integrated with the international youth culture of punk rock. Even my own laughter at wearing the pollera and braids played on the disjuncture of a U.S. gringa in clothing with cultural meaning in the Andes. And most certainly, when Luis suggested I wrestle, irony was used to disrupt the usual interpretation of a mujer de pollera. Coulson, Seana

2001 Semantic Leaps: Frame-shifting and Conceptual Blending in Meaning Construction. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Jenkins, Henry 2007 The Wow Climax: Tracing the Emotional Impact of Popular Culture. New York: New York University Press. Levi, Heather 2008 The World of Lucha Libre: Secrets, Revelations, and Mexican National Identity. Durham: Duke University Press. Messner, Michael A,, Margaret Carlisle Duncan, and Cheryl Cooky 2003 Silence, Sports Bras, And Wrestling Porn : Women in Televised Sports News and Highlights Shows. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 27:38-51. Rahilly, Lucia 2005 Is RAW War?: Professional Wrestling as Popular S/M Narrative. In Steel Chair to the Head: The Pleasure and Pain of Professional Wrestling. Nicholas Sammond, ed. Durham: Duke University Press. Williams, Linda 2001 Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess. Film Quarterly 44(4):2-13. |

themes

All

archives

August 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed