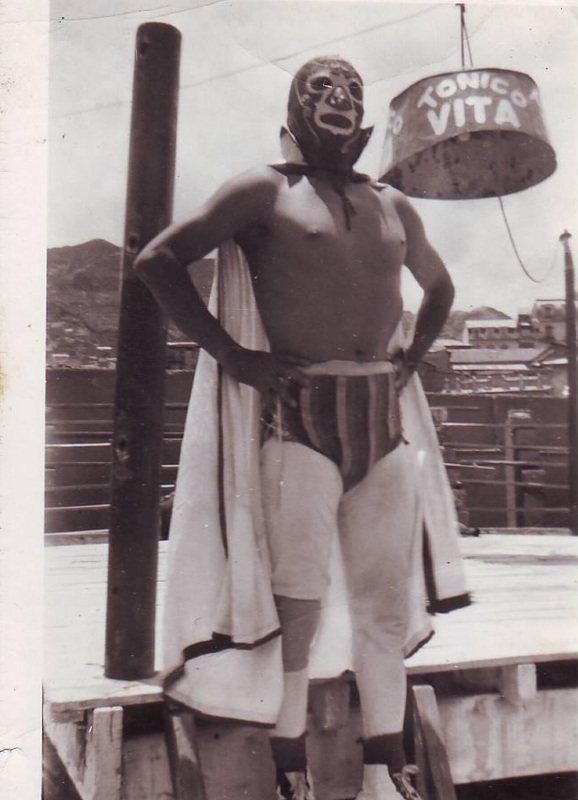

Much of the information I learned about the history of lucha libre since the 1970s came from Roberto, a wrestler in the Super Catch group. Though he was only 24, he explained to me that “Yo era fanatico! Me metía dentro de los vestidores, escuchaba todo de los luchadores. Es por eso que sé casi toda la historia de la lucha libre en Bolivia.” [I was a fanatic [when I was a kid]. I snuck into the dressing rooms, I listened to all the wrestlers. That’s why I know almost all the history of lucha libre in Bolivia]. He explained to me that during the 1960s lucha libre events took place in the Perez Velasco, a commercial area just outside of central La Paz that is a popular market for working class and middle class people. Luchadores usually wrestled in a makeshift ring and set up seating in a fútbol field. As Roberto told me, the costumes of the luchadores were not as “llamativos” [flashy] then, and almost everything was improvised. But by the mid-seventies, the Olimpic Ring was built in the neighborhood of San Pedro, and with its opening began what Roberto suggests many refer to as the “epoca dorada de la lucha libre boliviana” [golden age of Bolivian wrestling].

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, interest in lucha libre waned in La Paz. But in the late 1990s, a major shift occurred when Bolivian lucha libre first appeared on television. In 1998, a group of luchadores calling themselves Furia de Titanes [Fury of Titans] who were regularly putting on shows at the Olimipic Ring noticed TV personality Adolfo Paco in the audience. They approached him about beginning a lucha libre program on Asociación Televisión Boliviana (ATB) channel 9, and he agreed. The program was filmed in the Coloseo de Villa Victoria, and was an immediate success, which Roberto attributed to the fact that the wrestlers were highly skilled. In addition to large television audiences, the group began attracting long lines of people hoping to see the shows taped live. Luchadores gained notoriety and were featured in local newspapers and magazines. With the addition of several corporate sponsors, luchadores earned about $200 per event.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed