“Really, I am!” I want to shout at people I meet here in DC.

I suppose it’s a matter of social positioning, and I can’t really help it. Here I am a grad student and adjunct professor. I either stay in sweat pants all day or try to fight my younger-than-I-actually-am appearance by trying to dress like an academic. I hate when librarians ask me if I’m looking at information for a class paper. But in La Paz, I am one of the cool kids. I wear vintage, rockabilly dresses or ripped jeans and t shirts given to me by tattoo artist friends. I’m a live music junkie, a tattoo shop groupie, booze-slinging benefactor, restaurant aficionada, mural-painting sidekick, dj enthusiast, and a legitimate luchadora who rarely pays for a drink.

I came back in a depressed state, and googled “post-fieldwork depression.” Most of what turned up was written by people who disliked their field site and were depressed in the field. I felt the opposite. I longed to return to my friends, my usual days of training, reading, writing, visiting friends workplaces or homes, nice dinners served by my favorite Belgian, and the free tequila shots that went along with it. I missed the guessing games of who I’d run into on the street (there was always someone, but you never know who). Slowly it gets better. Easier. I instinctively put paper in the toilet, and don’t turn my nose at tap water. I wait patiently at bus stops, and thoroughly appreciate my electric heater. But I’d happily give it all up, even knowing there are horrific electric showers waiting for me on the other side.

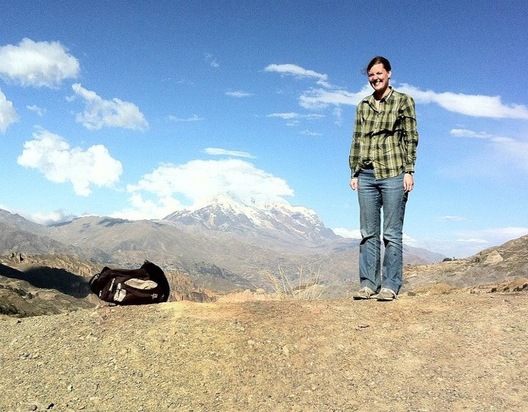

But this is how it happens. We re-integrate ourselves to the best of our abilities. We find the little things that make us happy (hot water in sinks) and try to forget the things that were so magical about our other home (evening light on Illimani). And at the very least, I’ve found a bartender here who hooks me up as well as I was taken care of in LPZ.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed