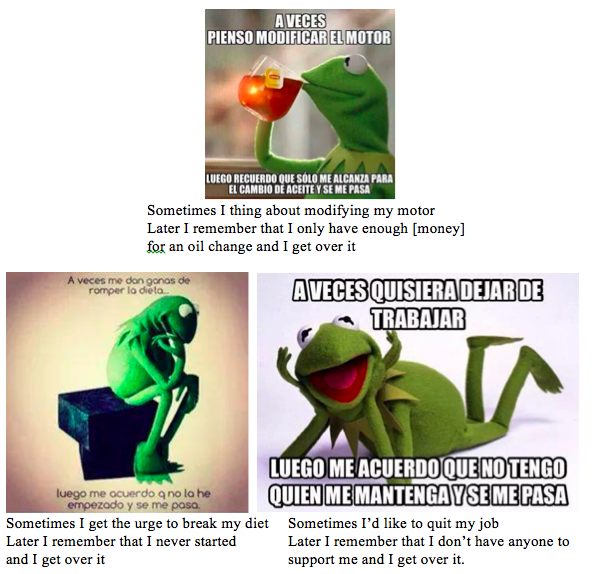

One particularly amusing example of this type of acceptance is especially apparent from a certain style of meme that overwhelmed Facebook in October of 2014. These “Rana René” (Kermit the Frog, in English) memes expressed a sense of abandoned aspirations. In these memes, the frog expresses desire for something—a better physique, nicer material goods, a better family- or love-life—but concludes that it is unlikely to happen, and that “se me pasa,” “I get over it.”

|

As many entries in the blog affirm, local cultural aspects are often reflected or made even more visual on social media. As I have written before of my fieldsite, there is a certain normativity that pervades social life. Material goods such as homes, clothing, electronics, and even food all fall within an “acceptable” range of normality. No one is trying to keep up with Joneses, because there’s no need. Instead the Joneses and the Smiths and the Rodriguezes and the Correas all outwardly exhibit pretty much the same level of consumerism. Work and salary similarly fall within a circumscribed set of opportunities, and because there is little market for advanced degrees, technical education or a 2 year post-secondary degree is usually the highest one will achieve academically. This acceptance of normativity is apparent on social media as well. One particularly amusing example of this type of acceptance is especially apparent from a certain style of meme that overwhelmed Facebook in October of 2014. These “Rana René” (Kermit the Frog, in English) memes expressed a sense of abandoned aspirations. In these memes, the frog expresses desire for something—a better physique, nicer material goods, a better family- or love-life—but concludes that it is unlikely to happen, and that “se me pasa,” “I get over it.” Similarly, during June and July of 2014 a common form of meme contrasted the expected with reality. The example below demonstrates the “expected” man at the beach—one who looks like a model, with a fit body, tan skin, and picturesque background. The “reality” shows a man who is out of shape, lighter skinned, and on a beach populated by other people and structures. It does not portray the sort of serene, dreamlike setting of the “expected.” In others, the “expected” would portray equally “ideal” settings, people, clothing, parties, architecture, or romantic situations. The reality would always humorously demonstrate something more mundane, or even disastrous. These memes became so ubiquitous that they were even used as inspiration for advertising, as for the dessert brand below. For me, these correspondences between social media and social life reinforce the assertion by the Global Social Media Impact Study that this type of research must combine online work with grounded ethnography in the fieldsite. These posts could have caught my eye had I never set foot in northern Chile, but knowing what I know about what the place and people look like, how they act, and what the desires and aspirations are for individuals, I understand the importance of these posts as expressing the normativity that is so important to the social fabric of the community.

0 Comments

I am something of a suspicious character in Alto Hospicio. First, I visibly stand out. As a very light skinned person of Polish, German, and English ancestry, I simply look very different from most of the residents of Alto Hospicio who are some combination of Spanish, Indigenous Aymara, Quechua, or Mapuche, Afrocaribbean, and/or Chinese ancestry. I am catcalled quite often, even while walking to the supermarket midday. These yells usually reference the fact that I am visibly different. “Gringa,” “blanca,” [whitey] and even “extranjera” [foreigner] are the most usual shouts. I hear. Even in less harassing ways, I’ve been pointed out on the street, as happened my first week in Alto Hospicio, walking along the commercial center a woman stopped in front of me simply to tell me “You look North American!” scurrying away before I could respond. maybe I look too much like her? Beyond the striking impression of my physical appearance, I was untrustworthy as a single woman. Having no family in the area, not to mention a male partner or children was often a red flag for people. Even though many people I met had left family behind in other countries or regions of Chile when migrating to the area, they usually moved with a least one family member or friend. In a lot of ways, my solitariness kept me solitary.

As I got to know people, at times I felt I was being given a test. A colleague at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile had connected me with some politically active students in Alto Hospicio, and they invited me to help put up posters for a candidate for local representative before the elections in November 2013. I met Juan in the evening, outside one of the local schools where we made small talk before they others arrived. He asked me about my opinions on the Occupy Movement in the United States, and I spoke frankly, though keeping in mind his connections to Chilean Student movements. We continued talking about US politics and he asked if I had been very involved during my time in graduate school in Washington, DC. He asked about my support for President Barak Obama. And he asked very detailed questions about who I worked for, where funding for the research came from, and to what institutions the results would be reported. Eventually the other poster hangers arrived and we walked a few blocks to the home of his friend, where we were to mix up the paste for the hangings. As he introduced me to the group, he explained that I was “a trusted friend.” So I had passed the test. Other tests of my trustworthiness took much longer. The first person I got to know outside of my apartment complex was Miguel, the administrator for the Alto Hospicio group I first joined on Facebook. Yet, it took over two months of online conversations before we met in person. Our chats at first were about the project, then about anthropology in general, while I asked him about his job at a mine in the altiplano and about his family. Later we conversed about television shows, movies, sports, and other hobbies. Eventually he told me funny stories about what his friends had done while drunk. I tried to reciprocate and realized my friends were far less rambunctious than his. Eventually, he invited me out with a group of friends to a dance bar in Iquique, and later I became friendly with his sister Lucia and her husband, often being invited to eat lunch in their home. Eventually one afternoon, sipping strawberry-flavored soda and finishing the noodles and tuna on my plate, Lucia asked Miguel how we met. He launched into a long story of seeing my post on the Facebook group site and being suspicious of it. He clicked on my Facebook profile and thought “What is a gringa like this doing in Alto Hospicio?” But his curiosity prevailed and he engaged me in conversation. As he recounted the story to his sister he eventually arrived at the night we had gone to the dance bar. “I was nervous standing outside the apartment, because I didn’t know what to expect. We had talked enough that I was pretty sure she was a real person, but I was still nervous. I thought maybe she wasn’t real. Maybe it was a fake profile. But then I saw her walking toward me and I just remember being really relieved.” To be clear, I was always treated with kindness and respect by the luchadores while training and performing. Of course there was always an element of tension around issues of gender and sexuality. I was a white woman, highly educated, from a middle-class background in the United States. I wrestled with working-class mestizo men from La Paz and El Alto, of varying ages. Our relationships were always professional. Occasionally one would invite me to dinner at his house, and I would have to weigh several factors—our interactions up to that point, the time he had suggested, whether other people would be present, and what I might know about his current familial and romantic situation—before deciding whether to accept or reject. Photo courtesy of Niko Scruffy D I rejected a request from a 50 year old luchador to accompany his family to a festival that would go late in the night, but agreed to meet him for tea later in a public restaurant in El Alto, trying not to alienate him to the detriment of my research. I accepted an invitation to a 27th birthday party for another luchador, which took place in a bar, and to which several of the other luchadoras were invited. I hoped this would allow us to be friends more than just wrestlers who train together. He tried to kiss me goodnight, but I quickly slipped away, and neither of us ever mentioned it again. These experiences were in part because I was doing research in a male-dominated social setting. Indeed, in many ways, they served to inform my analyses of what Bolivian women might experience in their own involvement in wrestling. Of course my gringa-ness, foreignness, and lack of familial ties to anyone in the group make my situation slightly different. But these instances still tell us something about gender relations within the context. But these experiences are not related just to my subject matter. In my current research, I have to be wary, not only of walking alone at night in Alto Hospicio, but also of the advances of police officers and public city officials when they send me non-work related Whatsapp messages. I have spoken with countless women about their similar experiences, one of whom was even evicted from her apartment in her fieldsite in a small conservative Middle Eastern area after refusing the advances of her landlord. To say that these experiences are frustrating is an understatement. They are not just an annoyance of daily life, but they profoundly impact one’s ability to do research, and maintain community ties. In just three short days it will be the two-year anniversary of the day I finished fieldwork. Yet I still feel the effects of these types of gendered relations. Today I received a facebook message from one of the more senior and well respected luchadores in La Paz. At first I was flattered to receive a message because he asked when I will be wrestling again. “Quiero venir a verte” [I want to come watch you]. But the conversation quickly turned Luchador: Your husband is Jorge*? Nell: No, I don’t have a husband. And unfortunately I don’t know when I will wrestle again. Luchador: Oh, then he’s your friend with benefits? That’s what he told me. [unclear if he’s referring to ‘friend with benefits’ or marriage] Nell: Um, no. We don’t know each other well, so I don’t feel comfortable commenting on my private life with you. Luchador: Yes, I know you. You’re the gringuita. Nell: Yes, of course, but we are not friends. I’m not sure why it matters to you and I find it disrespectful. Luchador: Sorry. Bye. *Pseudonym

And with that I most likely lost an important contact. Of course, I’m in a better position now, because my fieldwork is finished, some of it is published, and I’ve moved on to a new project. But I’m stuck now in a position of whether I even mention this to Jorge*, my former wrestling partner, and a fairly good friend. Do I continue as a friend always wondering if he is telling others that I am something of a significant other or sexual plaything to him? Do I mention it to him and confront the problem head on, most likely with little benefit either personally or professionally? Or do I assume what this older luchador said to be correct and silently stop being his friend. I realize this is the type of problem many anthropologists face, regardless of gender, regardless of region, and regardless of topic. But as I recently wrote about the perception of women anthropologists flirting, extroverted actions of men are interpreted differently than those by women. This is something that will not be “solved” easily, particularly when we consider that many times this happens in places where there is less awareness of “rape culture,” less ability for women to participate in social life, and more complicated relationships between race, class, cosmopolitanism, and locality. I do intend to keep up a conversation about it though. I had a unique opportunity this morning. I was given access to an apartment of a friend whose boyfriend (pololo) had started moving some of his things in. I took the opportunity to snap some shots of his stuff: the most important things for daily living he had transplanted into her space. I thought something a little different might make for an interesting post. the first things to appear: toiletries. the second thing he brought over: a large, flat screen television. mostly used for watching dvds of the walking dead. various articles of clothing and a motorcycle helmet. he sold the motorcycle about a year ago, but keeps the helmet on prominent display binoculars. i'm informed that so far they have only been used to watch neighbors on their balconies. stereo. a recent birthday present to himself skateboard. his polola says she's never seen him use it, but he occasionally comments on hills that he deems worthy of using it on. I suspect these items would be common in Northern Chile, but I cannot be sure. I am curious what might items might be the most important for a woman moving into her boyfriend's apartment. Would the amount of toiletries and clothing be bigger? Would the number and size of electronics be smaller? Or perhaps different in nature (hair dryers instead of stereos)? I am equally curious how these things vary from culture to culture.

I am reminded of my summers during grad school when I would pack up my car with the essentials and drive twelve hours from Washington D.C. to Chicago to spend two months with my boyfriend. Two boxes of books, a suitcase of clothes (another small duffle bag for shoes), my computer, and my bike helmet were the essentials. Obviously these things vary person to person, but this instant of beginning to move in with a significant other is not only important for the relationship. The things we move with us first, the things we deem most essential to daily life, these items of material culture give a unique and deeply revealing look into a person. I'm curious what other people have taken or would take when beginning to move in. Whether it is with a significant other, a friend, or simply an extended stay with family-what are the essential material possessions you take with you? Please leave a comment! The selfie has been the subject of much discussion in recent times, from valuations of vanity to criticisms of public figures taking self-portraits at solemn events. But the selfie is more than narcicism or pathology. For anthropologists, it can actually tell us quite a bit about daily life, leisure (or not so leisureful) time, and notions of beauty. About a month ago, I began analyzing the Instagram feeds of almost 75 residents of Alto Hospicio, most of them under the age of 25. Certain aspects of their Instagram usage were not terribly surprising. The example I present here is the selfie. Of their last 15 photos, all users averaged about 6 selfies (this was also fairly consistent between young men and woman, with only a .07 average difference). But what was surprising was the lack of artistry that seemed to be attributed to these photos. Filters were used, but subject matter was not particularly “beautiful.” Shots were not composed with symmetry, with horizontal lines leveled, or with the rule of thirds in mind. Neither were shots noteworthy for their “rarity.” As Jon Snow of Chanel 4 tells Nimrod Kamer in his short Guardian video about selfies, “I think if you’re somewhere rare, it’s worth [taking a selfie], or if you’re doing something rare, it’s worth doing it.” (see min 2:55-3:05 of the video below). But these photos are taken in family living rooms, while at work, and the backseat of an older sibling’s car. The exact places the users traverse every day. The definitive opposite of “rare.” Instead, they are taken in utterly mundane places. The ubiquity of mundane photos corresponds closely to Daniel Miller’s assertion that the intention behind photography is now not so much to produce a photograph, but that the photography legitimates the act of taking a picture. The transience of Instagram also legitimates the mundane self-portrait. It is not a portrait meant for a display of beauty, but rather a document of the moment. In this sense, it’s intention to amuse in the moment (or short period of time thereafter). It not only is briefly entertaining in the instant of taking the photo, but provides entertainment for a friend or follower who might view the photo. Further, through collecting likes and comments, the mundane photo may serve to break up a mundane day for the user. mundane photos in cars and at work The other most common form of self-portrait was the “sassy” photo. These appear like fashion magazine photos aimed at showing off clothing. They are often either taken in the mirror or by a friend. Hands are often on the hips, or in another “fashion model” sort of pose. It is important to note the difference here between sassy and sexy. Though the line between the two can at times be ambiguous, sexy photos usually involve the subject with little clothing, lying on a bed, or showing cleavage or abs. Sassy photos on the other hand are the type your mother might comment “Oh, you look so cute!” Notably, in these sassy photos, the clothing that is being shown off is rarely overly stylish. Hair is usually not noticeably done for a special occasion. Though these certainly pop up when people attend formal events (such as weddings or graduations), they more commonly appear with every day clothing and style. sassy photos The point of understanding self-portraits, including selfies, is that it lends us information about conceptions of attractiveness and beauty among particular groups of people. And attractiveness is something that most people think about when posing for a portrait that they will then share with their networks. This is evident here from bodily poses and facial expressions. Both are chosen in these photos, meaning there is an explicit, self-conscious presentation of the self. However, what seems quite clear to me, given the number of mundane photos and sassy photos that display everyday clothing and hair, is that people’s sense of what forms of attractiveness are worthy of display are actually quite “normal.” This is reinforced by my observations in Alto Hospicio in general. People are rarely dressed nicely. Jeans, shorts, and t-shirts are the norm. It is rare to see women in dresses or fancy tops. Most men wear sneakers and most women wear flip flop sandals. Women especially wear bright colors. Men also generally wear t-shirts, though during the week it is not uncommon to see men on their work lunch breaks wearing plaid short sleeved collared shirts with jeans. I’m reminded here of two different critiques of “critiques of selfies,” which both have come from self-identified “feminist” bloggers. The first, The Young Girl and the Selfie written by a woman who is an ex-PhD student in sociology, suggests that the selfie, represents the perfect contradiction of late-capitalism: young women’s bodies’ are both a target for consumption (particularly for “beauty” and “style” products) and judged not by those who inhabit them, but by those who gaze upon them. Thus, the selfie is the logical outcome of this combination of pressures. And when the selfie is demonized, it becomes “simultaneously the site of desire and pity.” Teen girls are “Young-Girls” [a type, not individuals], are spectacles, are narcissists, are consumers, because those are the very criterion that must be met to be a young woman and also part of society.

The second blog, The Radical Politics of Selfies goes beyond this first piece, arguing that while perhaps selfies may reflect “the way society teaches women that their most important quality is their physical attractiveness…not all [people] are allowed to see themselves as beautiful, desirable, sexy, or fit for human consumption.” For many, mass media representations of people who look like them are nowhere to be found. Magazines, television, movies, and advertisements depict people who are so far from physically similar to women of color, queer women, differently-abled people, and even people with a high percentage of body fat, that they are not only an unrealistic ideal, but have little to no resonance. Thus, the author concludes, that social media allows for people who do not fit these molds to find (and produce) proper representations of themselves. Alto Hospicio is the kind of place where people do not look like the actors in television shows they watch. They do not look like the news anchors on CNN Chile, let alone the South American telenovelas that most middle-aged women watch. They are generally darker skinned, shorter, wider, and have more indigenous features. And to dress or otherwise present themselves as such might not be authentic. Even though the city is a melting pot of Northern Chileans, Southern Chileans, Bolivians, Peruvians, and Colombians, they generally all blend together in a homogenizing soup of “normalness.” No one really stands out. Skin tones range from the light tan of mixed Spanish/Indigenous/German heritage to the dark tone of Afro-South Americans, but the casual clothing, low-maintenance hair styles, and lack of other physical beauty accents brings everyone together. Thus, perhaps the selfie acts as resistance against erasure: within this homogenizing crowd, for the region that is often forgotten politically and lacks representation in media. I had a few days that were emotionally rough last week, and on Saturday afternoon I decided the best thing to do was go to the beach for a head-clearing walk. As I hopped off the bus at Playa Cavancha, I felt a buzz in my pocket. I sat down on a bench and looked at my phone. Edgar, my former lucha libre trainer had sent me a message using his usual method-facebook. In all caps (which I will not replicate here, to save your eyes), he wrote: Nell, el evento grande es el 28 de octubre. Puedes estar aqui para esa fecha? Entraras conmigo. Nell, the big event is October 28. Can you be here for that day? You’ll wrestle with me. As it happens, 28 October is my birthday and I had been trying to come up with an excuse to go to La Paz around then anyway. So I replied with an immediate yes. Edgar and I then set about making plans in terms of training, publicity, costumes, and the event, which will be a benefit show to raise funds for children in La Paz with cancer. Edgar and I training last June But none of that really mattered. I couldn’t sit still. I started walking along the beach while continuing to send facebook messages with my phone. In the midst of the conversation with Edgar I was sending messages to my best friends in La Paz and New York. I sent messages to colleagues in Washington, DC and Chicago. I sent messages to my parents and sister. I sent a message to my favorite bartender who is a huge WWE fan.

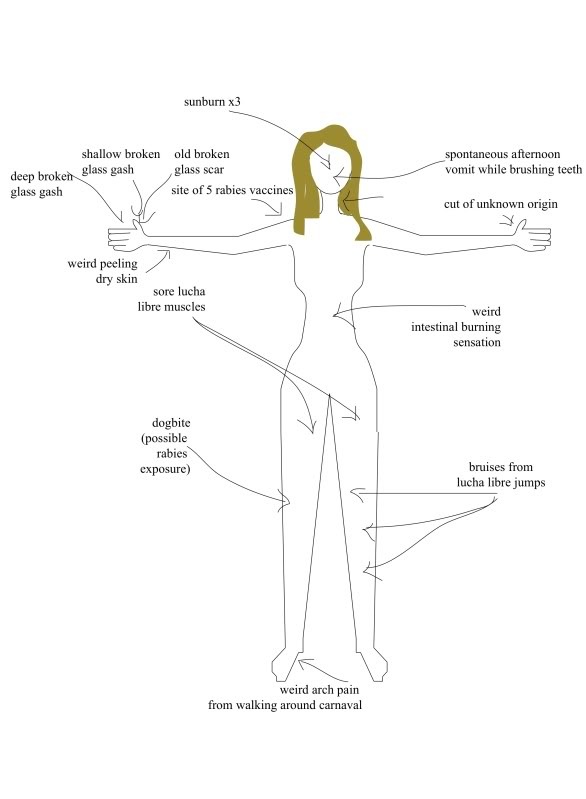

I tried to sit again. Edgar had taken his leave from the internet café where he had been writing me. I needed to talk to someone. I needed to gush. I pulled out a book to distract myself, but I couldn’t pay attention to the words. My legs were shaking. My fingers couldn’t stop tapping. I wanted to be in the ring. RIGHT NOW! I suppose, in a way, I see this as evidence of the success of my dissertation fieldwork. Not in an academic sense. Not even that the people I learned from like me enough to want me to come back for a visit. But it was successful because it’s in my body. Every time I return to La Paz a sudden wave of excitement comes over me. On the June day that I woke up in Lima, ready for a two hour flight to Bolivia, I couldn’t stop smiling. Arriving in La Paz makes my body feel different. A certain hard to attain comfort. It feels like going home. Wrestling, in a way, is the opposite of that comfort. Wrestling hurts. Muscles are sore, joints feel out of place. Necks are stiff, and just walking down stairs is nearly impossible the day after. Not to mention the dehydration and oxygen deprivation that go along with physical activity in the altiplano. But wrestling also does something else. It gives a jolt of adrenaline. It hurts, but it’s playful. It’s fun. But the kinda of fun that can’t be replicated alone. You need a partner. One you can trust. And for all the tension that may exist outside the ring, I trust Edgar 100% when I’m about to do tijeras. But then I started to worry. I won’t be able to arrive until the day before. It’s been almost a year since I even trained in the ring. Will my body remember how to do it? Will twists feel awkward or come naturally. Is this like riding a bike or speaking a language? I can only hope the muscle memory remains. Friday was the birthday of my friend Carrie (who I met in Potosí), a Canadian woman who is a graphic designer in La Paz. To celebrate, I met she and her friend Lisa who had flown in for the occasion at 2pm to get massages. They had just climbed Huayna Potosí, a 6000+ meter mountain, and their bodies were aching. I had been promising myself since finishing the final draft of my dissertation that I would relieve the aches of hunching over a laptop for months with a massage. We had reservations at a small local beauty shop on Calle Linares for 2:30, but as we were about to start walking they called us back. “Necesitamos cancelar la cita porque apagó la electricidad.” Well, what should one suspect in La Paz? Instead we walked to Hotel Europa, where my friend who works for the Inter American Development Bank always stays when he is in the city for business. We walked through the giant automatic revolving door and the climate was immediately different. Warm and slightly humid. I wouldn’t have been surprised if they were pumping oxygen into the building as well. After consulting the front desk, we walked through the lobby to the pool and spa and asked for massages. They could only accommodate one every 15 minutes, so Carrie began first, while Lisa and I used one of the saunas. We chose the “wet” sauna (labeled in English), thinking that some humidity might be nice in contrast to the usual dry altiplano air. This was a corporeal experience I had never had in La Paz. My body has been exposed to sunburns, dog bites and subsequent rabies vaccines, many scars from cut glass, back spasms, dislocated knees and other various injuries from wrestling, constant colds, constant shivers, a month-long undiagnosed illness I swear was typhoid, and what must be at least 90% of the parasites known to humans—not to mention the general lack of oxygen one lives in every day here. image from february 2012 But in the sauna it was hot, wet, and smelled of lovely herbs. Water droplets pooled on my skin and I couldn’t tell if it was sweat or condensation. Either way, the outside air is never moist enough for either to happen. At first I didn’t like the sensation of the hot wet air I pulled into my lungs, but after five minutes I breathed more deeply, hoping it would clear away any mucus that might be stuck in the respiratory system waiting to make me resfriada (or worse). After ten minutes it was time to start my massage. I was completely naked beneath my towel and slightly embarrassed in the brief moments between hanging it up and having my but covered as I laid face down on the table. But the young Bolivian woman didn’t flinch, and she set to work rubbing the backs of my thighs. I thought about how she might have learned to be a masseuse. How she came to work at this hotel. What neighborhood she lives in. Whether she lives alone, with her partner, with her parents. If she has children. If she takes a trufi or minibus back to her neighborhood after work. If she prefers tucumanas or salteñas. How she celebrates her birthday. After forty five minutes I wrapped my towel around me again and went to the shower with the small pack of shampoo and soap I was given. It was a nice hot shower and I wondered if the women who work in the hotel ever shower there, or if they’re stuck with the electric showers in their frigid bathrooms at home. Do they even notice, having grown up in this place that is always cold?

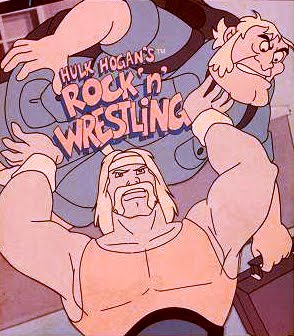

I had been back from a 2 week rendezvous in Bolivia for about 48 hours, and was contemplating returning to vegetarianism. For lunch, I made myself a tofurkey sandwich with vegan cheese and spicy honey mustard. I washed it down with the overly sweet canned maracuya juice I had been so excited to find at Safeway. As I chewed the last bite and slurped the last bit of juice, I walked into the kitchen to put my plate and cup in the dishwasher. There was some mustard stuck to the plate, so I turned on the sink to rinse it off. I put the plate and my hand under the water, and I literally jumped backwards. The water was hot. Plenty of times in my life I’ve had a similar reaction. Scalding water gushes out of a sink, or the shower suddenly turns ten degrees hotter with no warning. But this was not one of those cases. The water was not painful. It was just hot. Maybe even just warm. But I had become so used to washing dishes in cold water I was startled. I was so used to the possibility of warm water coming out of a faucet being entirely beyond comprehension that I had a physical reaction. And it got me thinking….. Now, before I go any further I want to remind all the dear readers that I am truly, utterly, madly in love with Bolivia. I don’t necessarily agree with all the politicians or politics. I don’t even necessarily agree with labor union tactics, or all the artistic expressions of Bolivians. In fact, I tend to critique the overly-romanticizing gaze many in the North Atlantic cast on Bolivian revolutions and protest and the like. But I love so many of the people, I love the thin air, I love the sun, and gazing up at Illimani, and buying Viva phone credit, and salteñas for breakfast, and even the long ride back from El Alto after a long day of having my body repeatedly thrown onto blanket-covered wood palates. me & illimani But I don’t love the water in the Bolivia. Point 1-Sinks. Only cold water comes out. This is all well and good, but when your hands are freezing from just the general cold that permeates daily life in the shade (and most sinks, being indoors, are in the shade), it’s a new level of annoyance. And since it is quite cold in the shade, and it seems that most water tanks are kept in the shade, when I say cold I do not mean room temperature, I mean a few degrees above actually freezing. Now, you can always boil water for washing dishes, doing laundry, etc., but that is not always particularly convenient. Though at least water boils at a lower temperature at such high altitudes. Point 2-Drinking water. Don’t do it. I brush my teeth with it, and rinse glasses (see above), and use plain old tap water for most daily activities. But I’ve also had enough cases of parasites and vomiting or diarrhea from unknown causes that I stay away from drinking the stuff. And Agua Vital by the 2 liter is cheap enough. But if you find yourself parched late at night without a bottle. Or worse, if you’re sick and go through your supply and feel too weak to walk uphill to the tienda to get more, knowing better than to drink tap water can be truly excruciating. Point 3-Showers. I have had good showers in Bolivia. Ekko hostel has some very nice gas-heated showers and I love them. Most of the places I have showered in Bolivia, however, have electric showerheads, which come in a variety of qualities. The good ones are good. Nice hot water comes out and lasts at least 5 minutes so you can actually wash everything you’d like to. But even these never seem to be powerful enough to heat the whole bathroom, so you’re still left stepping out from behind the curtain to a chill-inducing tile room. And then there are the bad ones. The electrocute you when you turn them off. Or sometimes start spewing sparks. Sometimes they only get luke-warm. Sometimes they just decide not to produce any warm water at all. And that might actually be preferable to the ones that purposefully trick you with about twenty seconds of warm water—just enough time to lather the shampoo in your hair—before they go cold for good. And others tease you with two-second alterations between pleasantly hot and scream-inducing cold. Oh, Bolivian showers, I do not miss you. the nicest bathroom i had in la paz, still with electric showerhead In February, I had the first of several flu-like experiences of last year. While chatting online with my friend Kate in New York, I complained: “If only I could just take a good, long, hot shower, I feel like it would clear out all the mucus in my head and I’d feel so much better.” She responded. “Do it! Better yet, fill up the tub with hot water and take a nice long hot bath!” I laughed to myself. My shower at the time did not even have a defining border. It was simply a shower head hung over the drain in the center of the bathroom floor. Oh a nice long hot bath. Sounds nice…. I realize these are complaints one could have about more than half of the places on this big earth. And these water issues won’t keep me from going back. But they sure do make me appreciate the water in the US. But the real point is, that the body adapts so quickly. When I pulled my hands back from the sink, it was not a mindful experience of water, but an embodied, conditioned response. And its only a small example of the ways that our conditions of existence, whether they be life-long, or temporary, impart themselves on our techniques of the body. _ This morning several Super Catch stars went to Palenque TV (canal 48) to record some messages aimed at children. The channel is going to start airing lucha libre, under the name Tigres del Ring, and the promo spots recorded will come at the end of commercial breaks. picture from appearance on Unitel, not Palenque TV _ Palenque TV is a project of Veronica Palenque, daughter of the late Carlos Palenque Avilés. Carlos was a presidential candidate in 1989 and 1993, running for the CONDEPA (Conciencia de Patria or National Conscience) party. In 1993, he received just over 14% of the vote, putting him in second place behind Goni (who garnered about 35.5%). Perhaps more interestingly, Carlos spent his time in the 1960s singing social-protest songs and cultivating long hair. He then became part of Los Caminantes, a pop-folk group that quickly became one of the most popular bands of time in La Paz. He eventually went solo, and the Bolivian National TV station (the only TV station in Bolivia at the time), asked him to do a weekly live music show aimed at indigenous and rural-origin peoples living in La Paz. He solicited Remedios Loza, or Comadre Remedios, to be his cohost on La Tribuna Libre del Pueblo [The Community’s Open Forum]. Remedios identified more closely with indigeneity than Carlos and dressed de pollera. She and Carlos remained close, and after his death, so ran for President in his place in 1997. However, it seems that Remedios had sharp tensions with Veronica, and left the program (for more information see Moore's piece here). Veronica herself then served in the Bolivian National Congress from 1997-2000. She first formed a radio station in 2000, with the objective to continue the line of social welfare, information, education, and training that Compadre Palenque (referring to her father) left behind as his principles, precents, and ideology. “Red Palenque Comunicaciones, fue creada el años 2000, con el objetivo de continuar la línea de ayuda social, información, educación y entretenimiento que el Compadre Palenque dejara bajo sus principios, preceptos e ideología.” In 2011 Veronica began the TV station, in response to the proliferation of pain, suffering, bad news, disasters, catastrophes, and negative news usually available on television. She decided to create a channel that emphasizes fun, entertainment, laughter, joy and positive aspects of life. Veronica explained, “El control remoto tiene que convertirse, a partir de hoy, en una ‘varita mágica’ que transporte al televidente a un oasis de entretenimiento y diversión, porque aquí sólo verá felicidad” [As of today, the remote control has to become a ‘magic wand’ to transport viewers to an oasis of entertainment and fun, because we only see happiness]. _ And, then, enter the luchadores: bastians of fun, entertainment, laughter, joy, and positive aspects of life (?). We started out recording a clip where we (attempted to) say “Hola Amigitos! Somos Tigres del Ring. Pronto por Palenque TV!” in unison. We pretty much failed and ended up just saying “Hola Amigitos” together, with Luis announcing who we were and Edgar promoting the station. After our group recording, we each each recorded a short PSA style message for kids. These messages were not our own of course, but were scripted and handed to us to memorize about half an hour before recording. I am unfortunately left to talk about the scripts in a passive sort of voice, because they arrived to us on little pieces of yellow notepad, handwritten by someone other than the camera guy who passed them off. We did have to wait around for Veronica to arrive, and my previous experiences with her have shown that she is quite involved in most aspects of the station. So I would venture to say she was the source of the scripts, but I can’t say for certain. I would also guess that the handwriting was a woman’s, but I’m no expert on gendering based on script. My little script was written in Spanish as “Practicar deportes, alimentarse sanamente, y alejarse de vicios son las claves de una vida exitosa. Ustedes pueden ser heroes. Es un mensaje de Lady Blade, junta con los Tigres del Ring. Estaremos pronto por Palenque TV.” But of course Omar wanted me to do it in English (I didn’t mind), so I translated it as “Practice sports, eat healthy, and stay away from drugs are the keys to a successful life. You can be a hero! This is a message from Lady Blade and the Tigres del Ring on Palenque TV.” So yes, my little bit was chock full of certain moralizing messages that seem to conflate bodily health with some sort of emotional or social decency. And I suppose this is not surprising given the social welfare, information, education, and training espoused in the radio station’s mission statement. But what was especially interesting were the references to “our country” most of the other luchadores had in their scripts. Luis’s was the most explicit. His went something like: “To support our beautiful country, Bolivia, we need to work hard and stay healthy.” Carlos’s began with “Drugs and alcohol destroy your life! But we can be heroes for our country, Bolivia by staying fit and respecting each other.” Edgar’s concentrated on keeping Bolivia beautiful by recycling, caring for water, and not polluting. Finally SuperCuate’s was short and simple, “The values of respect, education, and consideration make us heroes for Bolivia.” This reminded me quite a bit of the “lessons” of Hulk Hogan’s Rock n’ Wrestling show from the 1980s. Indeed, US wrestling is often fraught with nationalist storylines which help to delineate heels from faces (villains from good characters). And nationalism has certainly had its place in my experiences wrestling in Bolivia. Primarily, I’ve had to walk a fine line promoting the US, but maintaining my status as a technica (good character). I wave at the kids, and they seem to love me, which helps. But when E came to visit and made an appearance as my partner on the program “La Revista," he played the rudo well, telling the Bolivians they had a lot to learn from the US where “real” wrestling takes place. _ But mostly its always struck me as strange that wrestlers, people who enter the ring and seemingly commit acts of violence, are poised as role models. As Nick Sammond writes, “Wrestling is brutal and it is carnal. It is awash in blood, sweat, and spit, and…depends on the match—the violent and sensual meeting of human flesh in the ring” (Sammond 2005:7). Is this really the way to teach values like respect, education, and consideration?”

But I suppose meeting “them” where they’re at is a viable approach. And if luchadores are icons that kids look up to, encouraging them to take care of themselves, each other, their country, and the earth isn’t all bad. Especially given the fair amount of inferiority complex some Paceños I've met have about their country, perhaps encouraging a little nationalism isn’t entirely bad (though still complicated). Most wrestlers learn to wrestle in a gym. They may start on mats on the ground, and eventually work their way into the ring. I learned on a mountainside overlooking the Sopocachi neighborhood of La Paz. At just under 4000 meters below sea level, even breathing is sometimes a feat. To add to my corporeal distress, the day I began training I arrived with a large dog bite on my right leg, and a left bicep that was puffy and red from rabies vaccines. We started with sprints back and forth. I had been in La Paz 3 weeks, but my lungs were still not ready. My legs were fine, but I felt a burning in my chest. I rested what seemed like a good amount. The burning persisted. I did more sprints, and the burning remained. I was a little dizzy. And then we moved on to summersaults. After the vueltas (summersaults) I moved on to the mariposa (butterfly). I watched Daniel do it a few times, and then it was my turn. It looked complicated. I worried I’d fall on my head. I worried Oscar would drop me. I worried I’d look like an idiot. But there’s only one way to learn and that’s to run up, put your hand on his leg and throw your body over. So I did. “Bien!” And I tried it again “Eso!” Hm. This isn’t as hard as I thought. tijeras That first training session, I learned how to fall, I learned the mariposa, tijeras, and the casadora. And I learned the most important secret of lucha libre: not whether it is real or fake, not whether it is choreographed or improvised, not whether winners are real or pre-determined, not even whether the pain is real or exaggerated. But I learned that despite the pain, it is fun. And people do it because its fun. And people enjoy watching it because its fun. And people build their lives around it, and are passionate about it, and love it because its fun.

|

themes

All

archives

August 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed