On October 12 I went to the Library of Congress to dig around in old Bolivian newspapers. I was hoping to find evidence of the beginnings of lucha libre in the country. While I waited for my requested microfilm to be pulled, I wrote this:

Here I am in a strange, bureaucratic, florescent-lit room looking up Bolivian newspapers from 1965. I feel like I should be in Café Berlin instead. Or maybe that place on Camacho V took me while we waited from micración to open for the afternoon. I want a salteña and a Paceña. I want to loose my breath, sweat, and shiver all at once while I walk home. I want to wake up at night from the drafts or fall asleep on a mattress on the floor. But even as I write this, I look down and see my scar. And I smile. I hope it never fades, because some of the memories already have.

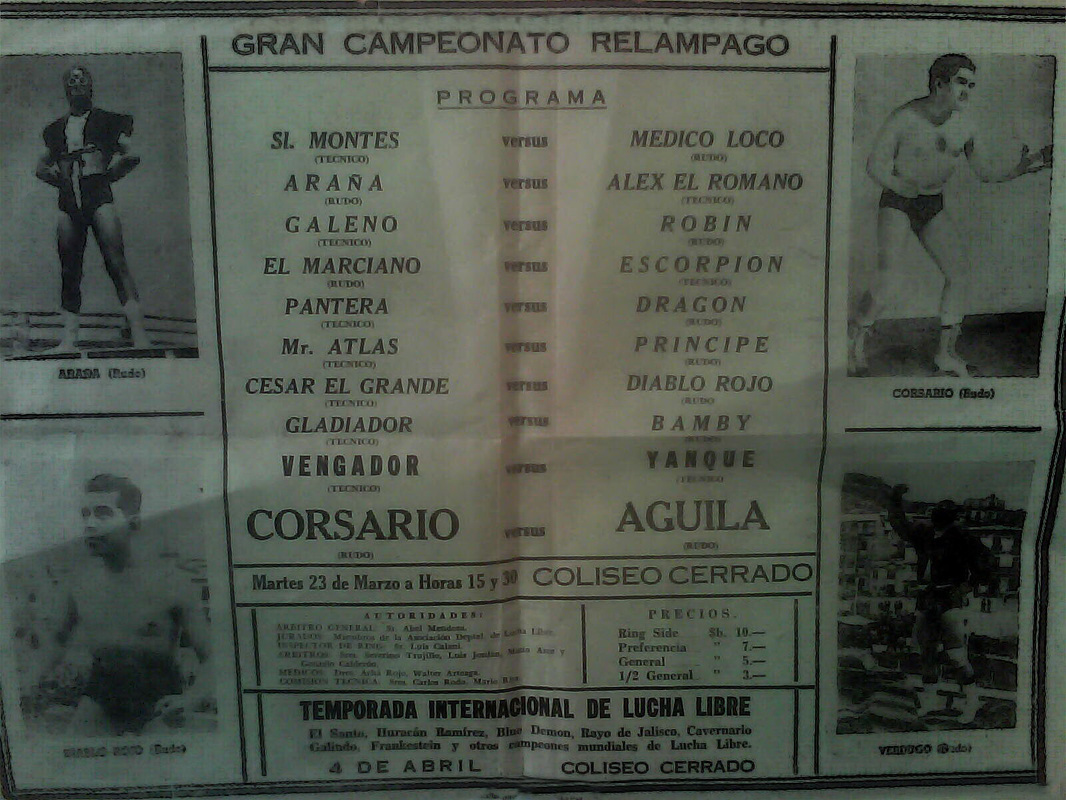

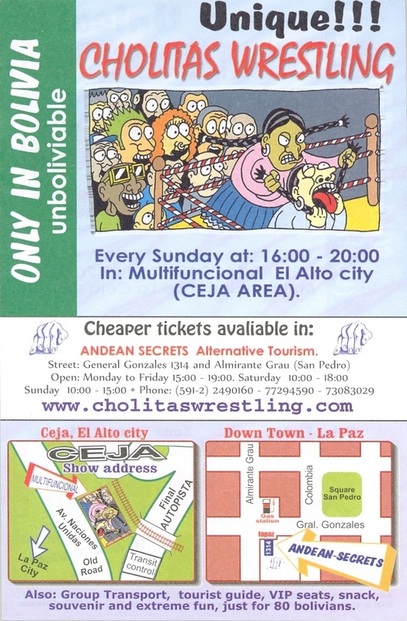

I began with 1965, owing to former luchador and current trainer DT’s memory of starting to wrestling in that year. He mentioned that he began wrestling when Mexican wrestlers Huracán Ramírez and Blue Demon arrived in La Paz and taught Bolivians the craft. The Lucha Libre Bolivia blog has also featured newspaper clippings from such events in 1965, seemingly corroborating DT’s story.

The most promising detail I found was that on March 15, 1965 in the Suplemento Deportivo, there was an announcement for an “important meeting” of the local boxing association, that referred to the group as the Asociación de Box y Lucha Libre, when usually (and subsequently) it is simply referred to as the Asociación de Box

Right.

So, I sat myself down again, yesterday at a microfilm reader and got to work. On January 18, 1952, I found an announcement of a new open air theater, Teatro Lirico, which would include a ring “para box y catch” [for boxing and exhibition wrestling]. Again a sign that lucha libre was happening with enough frequency to warrant its mention in possible uses of a new facility, but nothing concrete or exciting.

And then, I got to March 12. And there, like a little gem, was an article titled Se Proyecta para Junio Gran Temporada de “Catchascán.” My heart skipped a beat. Not only was this a real reference to a real lucha libre event, but I thought maybe the quotation marks around catchascán might indicate the word is new, not well-known, or institutionalized yet (looking for confirmation or references on this currently…). The article describes the arrival of a number of luchadores who were touring South America and stopping by La Paz on their way to Lima after stints in Buenos Aires, Santiago de Chile and Rio de Janeiro. The wrestlers mentioned are a Spanish luchador, Vicente García (who seems to have mentored Chilean wrestlers at some point), Renato “El Hermoso” (who seems to be Argentinian), Barba Roja (a Mexican), Bobo Salvaje (another Argentianian), and Takanaka hailing from Japan. Alas, none of these men have been mentioned by the oldest luchadores I’ve spoken with, and only one is Mexican. And once again, more questions were posed than were answered.

So the “history” of lucha libre in Bolivia is about as clear as the “realness” of professional wrestling itself. Which is to say—not clear at all. But, as Heather Levi told me, perhaps it’s the mythologies that are more important than the histories. How are people remembering it and why? What identities are being constructed? What memories are being instantiated? Through these “histories,” what stories are people like Kid and DT telling about themselves?

For me, these questions are still unanswered.

Near the end, I was also excited to find some references to Luna Park, which is the park where Kid suggested that the Mexican luchador matches took place. When I was later transcribing the interview with Kid, I wasn’t sure I had heard “luna” correctly, and asked R if he knew where it was. R had been with me at the interview and Kid had specifically asked him if he knew the park. In the recording you can hear R respond by saying “Oh yes, I know it.” Though, of course, when I asked him about it during my transcribing, he said he had never heard of the place and had been lying. To which I could only giggle. So, I was quite pleased to find that on February 7, 1952 an anniversary celebration of the park featured “en el ring, figures del Boxeo nacional e internacional” [in the ring, figures of national and international boxing]. It would of course make perfect sense for lucha libre to have begun in a place known for boxing events. “Fantastic!” I thought. “This place does exist!” And then the article mentioned that President Perón and his wife attended. "Strange," I thought. And then I realized the article was referring to a park in Buenos Aires. Well, so much for that making anything clearer either…

RSS Feed

RSS Feed