And I quickly learned that for the luchadores of SuperCatch, facebook functioned as a way to stay in touch with many people abroad. My fellow Super Catch wrestlers saw the connections they were able to make on the internet as one of the most important ways of achieving international exposure. Whether inviting foreign luchadores to perform in La Paz or organizing their own trips to perform in Lima, Santiago, or Buenos Aires, Facebook was a primary way of connecting with different international groups of wrestlers. Often after a long afternoon of training in Don Mauricio’s ring, we would walk back to Avenida 16 de Julio and stop in one of the small restaurants for the daily special. After shoveling giant plates of silpancho, pique macho, or falso conejo into our mouths and washing them down with mocochinchi (a peach flavored drink), we would walk a block further to the small shop with several computers set up as an internet café.

For just 50 centavos an hour we would sit in a row at the computers, and everyone had a browser tab open with Facebook. Of course the luchadores would look at their Paceño friends’ pictures and send birthday wishes to cousins or schoolmates, but they spent most of their time connecting with wrestlers from other countries. All of the luchadores were members of online virtual Facebook groups of South American and international wrestlers. Occasionally these groups would have scheduled discussions, and the Super Catch luchadores always made a point to participate. Discussions ranged from the latest WWE pay-per-view program to moves wrestlers were working on. But the most important were discussions about travel and the arrival of visiting wrestlers.

I often would finish sending emails to friends in the U.S. and exhausting everything I could think of to look at on Facebook long before they finished their conversations with Peruvian, Mexican, and Spanish wrestlers. Sometimes I was relieved to be asked to translate an English language message that someone received from a U.S. wrestler just because it gave me something to do. We would stay at the internet shop sometimes for almost two hours, as I silently whined in my head that it was already 9pm and I just wanted to go home and sleep. But I slowly understood the importance of these interactions. For just 0.50 Bolivianos an hour (about $0.07) the luchadores were actively participating in what they saw as an international “community” of which they wanted to be a part.

As Schein point outs, it is electronic media that allows this sort of “supralocal transmission” to occur. The interactive nature of the internet (even if it was infuriatingly slow at times), allowed for a horizontal exchange that unlike media of television and film, “brings into possibility an imagining of community on the scale of the globe” (Schein 1999:359). Within these new communities identifications may be refashioned. For the luchadores, their involvement with wrestlers outside of Bolivia allowed them to see themselves and the group as part of “international lucha libre” despite the fact that they rarely if ever traveled to perform outside of Bolivia, and visits by foreign wrestling groups were only occasional. These connections allowed them to imagine the eradication of economic exclusions, and restrictions imposed by state borders that their own particular citizenship determined. Yet, even as cosmopolitan exchange allowed for the imagining of mobility, it was also conditioned by the endurance of relative physical immobility (Schein 1999:269) that the luchadores knew was part of their reality. Appadurai writes that “Fantasy is now a social practice” (1996:7) and many people long for horizontality described by Anderson (Appadurai 1983:7), without global differentials of power and wealth (Schein 1999:369). For the luchadores, these differentials were manifested in their desire for legitimacy.

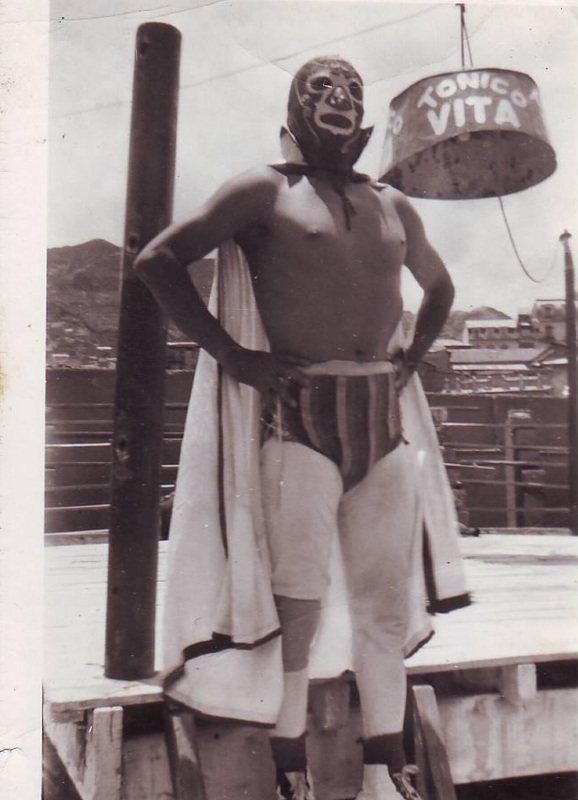

Yet legitimacy continued to be fleeting for the Super Catch luchadores. Clearly the reputation of Bolivian lucha libre among wrestlers outside of Bolivia was part of a global dynamic in which Bolivia either appeared invisible or was understood as derivative of better established wrestling traditions in Mexico or the United States. As Rocky Aliaga, a Bolivian who now wrestles professionally in Spain explained to me, people in other countries only knew what they saw of Bolivian lucha libre on the internet. “Aqui llega informacion de monstruos, momias, hombrelobos...En Bolivia hay talento y nuevos valores, pero sin dar oportunidad. Cada una lucha hasta tres veces para no dar oportunidad a jóvenes. Por eso se disfrazan de monstruos” [Here they find information about monsters, mummies, wolfmen…In Bolivia there is talent and new values, but without opportunity. Each match of three falls doesn’t give the opportunity to young wrestlers. That’s why they costume themselves as monsters]. Rocky confirms here what those luchadores still in Bolivia suspect: that in the larger world of exhibition wrestling they are seen either as a joke or as underdeveloped. But the luchadores often attribute this formation to the local dynamics of clowning rather than global processes

RSS Feed

RSS Feed