An anthropologist friend commented on the Brazil v The Netherlands game for third place via Facebook: “Why is everybody hating on Brazil so bad? A colonizing nation kicked a neo-colonized nation's ass. And got most of Latin America, aka the neo-colonized neighbors, to cheer about this. Helloooo, false consciousness????”

This confusion I think is reasonable and common for people in North America. And I am no expert on futball fandom in South America, but I’ve now seen two separate World Cup cycles from this half of America (one from Lima, Peru and one from here in Northern Chile) Being an anthropologist, I’ve noted certain things. Also, I’m going on three years around these parts and I know some things about international relations. So here goes…

First, at least in the Andes, Brazil retains it’s “far away paradise” image. People with money go to Rio for vacation, spend their time on the beach, eating tasty things, staring at hot people, dancing Samba, possibly partying at Carnival, and maybe even going to a brothel. For others who are not as well off, it is a mystical land that is close enough to dream about but not quite reach (at least for now).

Yet, part of that partially obtainable dream is Brazil’s economy. Brazil’s economy ranks seventh in the world by both Gross Domestic Product and by Purchasing Power Parity. They fall behind the United States, China, Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. The next Latin American country on the (GDP) list is Mexico, which ranks 14th, and the next South American country is Argentina which ranks 26 (and then Chile at 36). In essence, for my friends in Northen Chile, Brazil might as well be Miami—in fact Chileans don’t even need a visa to enter the US). For others, like Bolivians, Brazil may technically be far easier to enter than the United States, but exchange rates are so unfavorable to the boliviano that it would be difficult for a middle class family to afford vacationing there. Essentially, Brazil is closer, but their economic position is much closer to North America and Europe than their South American neighbors.

But even if we believe Lukács that all relations are structured by the condition of capitalism (and I’ll leave that up to you to decide), these relations run much deeper than simple exchange rates. Brazil for reasons economic and otherwise often has an excellent national team. This is partially why North Americans even notice that they exist. When’s the last time any North American tuned into a Bolivian game? Or can even find Bolivia on a map for that matter? But the fact that Brazil consistently fields a good team means they get international attention. These economic and futball success factors are indeed a large part of why Brazil was chosen to host the World Cup.

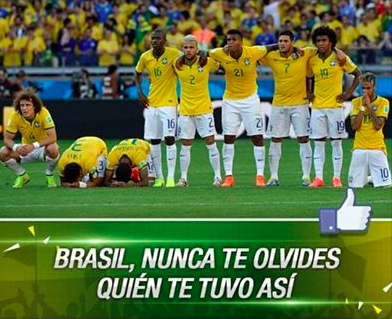

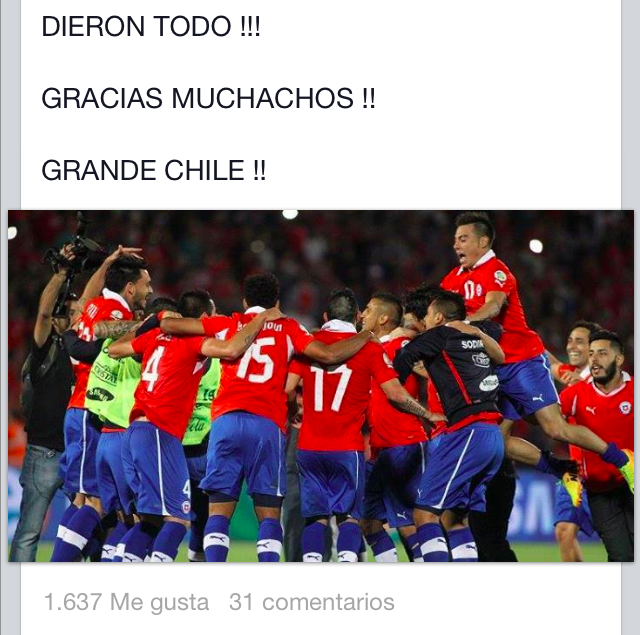

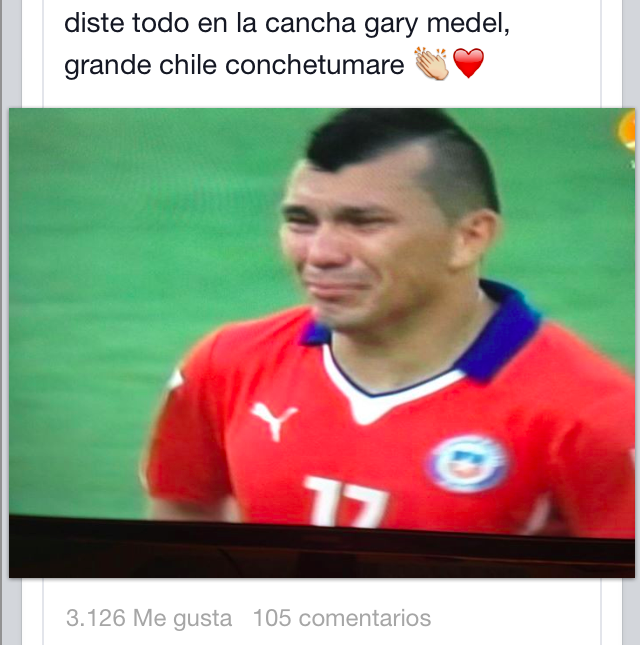

But this futball success also means that they usually beat their neighbors at the game that is most important to most fans. Chile, in particular, has been eliminated from the World Cup by Brazil in 2014, 2010, 1998, and 1962. That is every single time they have ever made it out of the group stage. Just (literally) bringing the Brazilian team to it’s knees this time around was a source of national pride. Brazil has also won 4 of the last 6 Copa America championships. In high school sports, they would be the fancy private school that hires university coaches and always makes it to the State Final.

Again, similar to Brazil, Argentina is a futball powerhouse. They have qualified in every World Cup for the last 40 years, and only once have not made it out of the group stage. They have played in the final game in four of the last 10 Copa America tournaments. They are also home to the most visible and recognizable South American futball club, the Boca Jrs. And they have Messi (who is often considered arrogant and dismissive of fans). In fact, one Bolivian fan told me “The Argentinos are individualistic. They don’t work as a team, but try to be the star like Messi, the worst arrogant one.” Again, we’re talking private school here.

But possibly more importantly, Argentina is a “natural rival” of Chile (and Brazil too). They have had territory disputes. And according to at least one Chilean, “they laughed at our loss [to Brazil].” A Bolivian woman reflected general South American stereotypes of the country: “Argentines are snooty. They think they’re gods. Go ahead and cry Argentinos!” These feelings are obviously not homogenous. One miner who watched the game while at work told me that bets among coworkers were even for Germany and for Argentina. And there are plenty of fans who think that “If you’re from South America you should always support our neighboring country, just as Europeans support Germany. It’s a shame.” But the point here is that while people may have personal reasons to support Argentina or Brazil, or may feel a sense of South American unity, there are also many structural reasons South Americans do not support these teams.

In relation to my friend’s Facebook question, I think it’s important to realize that while colonialism certainly shaped the form of today’s nation-states and alliances to a great extent, this is not the full story. Just as assumptions that South Americans were less civilized than their European colonizers, it would be incredibly Eurocentric to believe that some sense of historical unity against Europe would trump the present day tensions between South American citizens. History is important to them, but so are their present relationships to their material conditions of existence. From a global perspective, South America might not be the most sought after school district, but there are still a few kids who always have the latest Air Jordans.

*Yes, I know this is more commonly spelled football, fútbol, or soccer. But a Spanish-speaking friend recently misspelled the word this way, and I think it's useful for North American Spanglish speakers like myself, who need to avoid confusion with "American Football" and not alienate non-North-Americans (or Aussies or Kiwis) who might not be keen on the word soccer. So there you have it. Spread the word!

See my other blogs on the World Cup:

The World Cup on Social Media Worldwide

Seeing Red: Watching the World Cup in Northern Chile

Part of the Red Sea: Watching the World Cup in Northern Chile

Tears for the Red Sea: Watching Chile Lose in the World Cup

Goldstein, Donna

1999 “Interracial” Sex and Racial Democracy in Brazil: Twin Concepts? American Anthropologist 101(3):563-578.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy1992 Death Without Weeping : the Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil. Berkeley: University of California Press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed