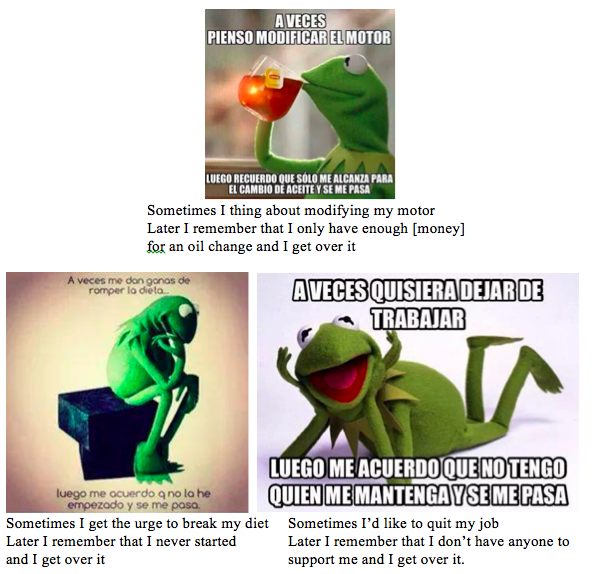

In field Alto Hospicio, a marginal city in northern Chile, some of the most interesting ethnographic details have to do with the ways young people use collaboratively managed Tumblr accounts to create a sense of a community through language play and humor, extending beyond the local area to a nationally imagined community. This identification with a national community is actually quite an anomaly, because in many senses the people of Alto Hospicio often distinguish themselves from people in other regions of the country, considering themselves to be more marginal and exploited than the average Chilean citizen. The city is located in a booming copper mining area, but most residents are low-level workers in the industry, and watch as the massive profits end up in the national capital of Santiago or abroad in Europe, North America, and Australia. In general, most citizens envision themselves as economically disadvantaged and politically (and geographically) marginalized. While marginality is often used as a category of analysis within the social sciences, generally to describe the conditions of people who struggle to gain societal and spatial access to resources and full participation in political life, in the case of Alto Hospicio, marginality is incorporated into the ways citizens view their own position in contrast to those people the see as more powerful in the center of the country. In actively distancing themselves from cities such as Santiago – both in daily life and through their online activity – residents of Alto Hospicio see their marginalized city as part of the way they perceive them- selves – not as victims, but as an exploited community that continues to fight for its rights. Yet they strongly identify as Chileans, citing their cultural affiliations rather than political power.

Please read the full blog on THE GEEK ANTHROPOLOGIST

RSS Feed

RSS Feed