The patriarchy is a judge

that judges us for being born

and our punishment

is the violence you don’t see…

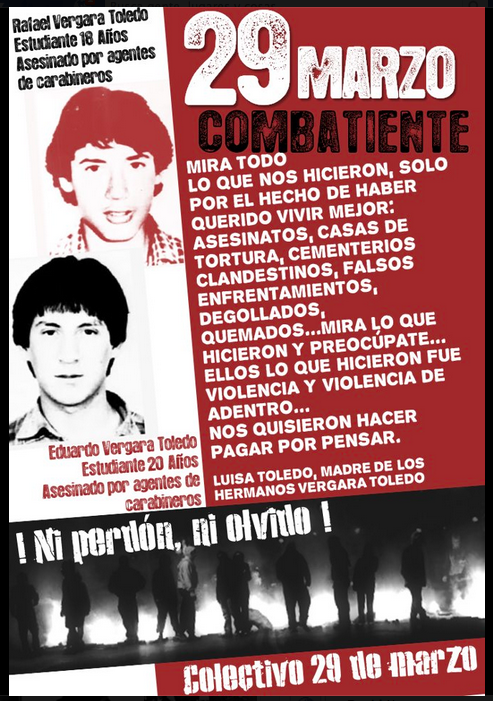

The lyrics continue on to connect patriarchal state structures to femicide, disappearances, rape, the police, judges, the state, the president, and perhaps most importantly, impunity. The most powerful phrase, repeated twice, is:

The oppressive state is a rapist.

The rapist is you.

(lyrics from Women’s March 2020)

To read the full article, click here to go to Anthropology News

También se aparece aquí en español, después del inglés

RSS Feed

RSS Feed