Chilean Media Amidst Protest

I woke up Saturday morning with a direct Instagram message from my friend Mateo. “Share please,” it said, with a formatted text with the title “State of Constitutional Emergency in Chile, October 2019.” In the 3 days since, he continued to send infographics and then videos of protests, each time asking me to share them.

“The media here is making it seem as if we are violent delinquents, but we are mostly peaceful. And the media outside of Chile isn’t showing anything. Please help us share the message.”

As Chile has recently erupted in protest, police violence, and other sorts of chaos, from the Atacama to Patagonia, media is taking on a central role in the tensions. From 2013-2016 I lived in Chile, in both the capital of Santiago, and the far north region. Coincidentally, Mateo lived in the north while I did, though he had spent most of his life in Santiago, and has since returned. His use, as well as criticism, of media, along with dozens of other Chileans in both the metropolitan region and the north, provide important insight to many protestors’ grievances and tactics in this historic moment.

Chile in State of Emergency

On Sunday 13 October, Chile’s Transport Ministry announced that the Santiago metro would raise fares by 30 pesos (about 4 cents in USD). This seemingly small increase, however, must be placed in the context of the average Chilean’s monthly salary around $450.

In response students started organizing fare-dodging acts all over the city. Fare dodging is not uncommon in Santiago where late-night bus drivers are often defenseless against crowds of young people pouring onto the bus or jumping turnstiles without paying. This coordinated effort however far exceeded previous levels.

Soon the protest spread beyond students, particularly when politicians made poorly calculated comments in response (link to The Minister of Economy, Juan Andrés Fontaine, indicated live on TV that workers should get up earlier to catch public transport when the fare is lower).

But these protests are not simply about a fare increase. As many hashtags and memes attest, it is not about 30 pesos, but about 30 years of inequality.

Chile is classified as a highly developed country by the World Bank, but also consistently ranks as having the very highest rates of social inequality among such countries. A meme which was first shared with me on Sunday October 20th, depicts an iceberg with “Increased public transport cost” above water and a long list of other effects of neoliberalism below the surface: poor but expensive education, deficient healthcare system, pension system crisis, inadequate salaries along with high disparity between general public and the political elite, precarious employment, police corruption, corporate corruption and collusion, and even the privatization of water.

These grievances are attributed to the last 30 years—the time since the “No” vote which ended the brutal dictatorship of Agosto Pinochet. While “neoliberalism” is often a catch-all phrase for economics associated with the free market, post-1985, in Chile it is directly connected to Pinochet’s regime, who specifically brought Milton Friedman to the country in 1973 to impose economic “shock” theories as a test case. His policies privatized companies and resources, deregulated business, cut social services, and opened the country to unimpeded imports. Inflation then spiraled to 374% and unemployment reached 20% per cent. The government almost entirely defunded social services, the social security system was privatized, health care became a pay-as-you-go system, and public schools were replaced with charter schools. Pinochet’s government maintained these policies until 1982 when the Chilean economy crashed – debt exploded, hyperinflation took hold and unemployment rocketed to 30 per cent. Pinochet’s regime was finally defeated in a democratic election in 1989. However, many Chileans feel subsequent democratically elected administrations have only intensified the export-oriented neoliberal reforms, though with less violent and totalitarian control.

Chilean Media

While Reporters without Borders gives Chile a favorable score for press freedom, they note that “pluralism and democratic debate are limited” by media ownership concentrated among the elite who share interests with those in political power. Community media, particularly in radio, has a long history in the country, but its ability to spread information widely is not always adequate.

At the same time, about 78% of Chileans have Internet access and most are well-connected on social media. Yet as I found in northern Chile, many people shy away from discussing politics openly on social media, in part a lingering result of sixteen years of dictatorship. While many northern Chileans post funny memes about how politicians are disconnected from the lives of “real Chileans,” they shy away from direct criticism or analysis of politicians and policy. One exception I found was that during the April 2014 8.2 Richter scale earthquake in the region, northerners realized the world was paying attention and use primarily Facebook and Instagram as stages for calling attention to the lingering effects of the natural disaster and the national government’s slow and inadequate disaster relief.

Northerners also use social media to demonstrate the ways they differ from even regular people in Santiago. They see Santiago as a place of consumption, whereas the North, known for its rich copper deposits, is a place of labor. Santiago is a place of strangers and vulnerability to urban crime, while northerners watch out for one another. They see Santiago as the beneficiaries of their work, as wealthy and politically elite, even as they may know working-class people there. Overall, Santiago is framed as having very little in common with the northern region of the country.

Social media use in Santiago is more similar to the types of political engagement we see by those connecting online from countries in North America or Western Europe. Most people are forthright about their political stances and use social media as a space for criticism and at times, campaigning. While they do not take much time to compare themselves with those outside of the metropolitan region, northerners would use this fact as further evidence that those in Santiago hardly realize anyone else in the country exists.

October 2019

Because Mateo has lived most of his life in Santiago, I was not particularly struck that his feed quickly filled with protest-related content. But just a day later I began to see photographs and videos of protests being posted by Chileans in the north of the country. People shouting in the street in Arica, Iquique, and Antofogasta appeared in my Facebook and Instagram inboxes with little comment other than “please share.” In my 18 months living in the region, I had only ever seen those sorts of crowds in the streets after the national football team won a championship.

This use of social media was a departure from the sorts of usual posts northerners shared. It reminded me of post-earthquake posts in the ways they attempted to address a global audience in order to bring an issue of injustice to attention. These posts differed from the somewhat apolitical posts after the earthquake. The social media content of northerners in the last few days has been highly political, often accompanied by hashtags calling for the president to resign.

Thus, it is clear that northerners see these calls as legitimate and possible. They are not apt to share such sentiments as a pipe dream, but rather save their political calls to action for moments in which they believe they are justified, possible, and aided by international attention. Essentially these posts demonstrate that northerners sense a real possibility of change.

We are united

On October 20, President Piñera, flanked by almost 2 dozen military leaders, declared on national television, “We are at war against a powerful enemy, unrelenting, that doesn’t respect anything or anyone, and that is apt to use violence and delinquency without limit, that is apt to burn our hospitals, the metro, the supermarkets, with the only purpose to produce as much damage as possible.”

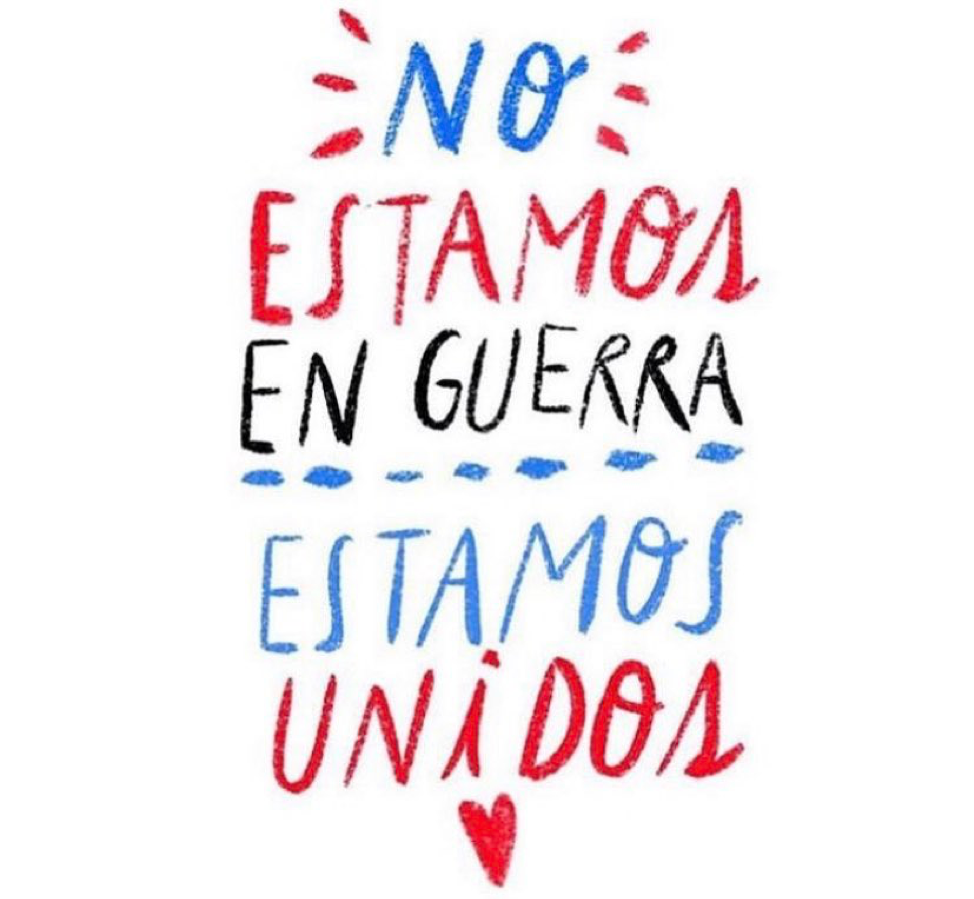

In response, Chileans throughout the country took to social media, asserting “We are not at war, we are united.”

While nationalist discourses in Chile are common, they are usually colored by equally powerful senses of regional belonging, that may just as easily highlight difference among Chileans as call for unity. Yet, social media is now showing this slogan to be quite true. For a moment, Chileans throughout the country are seeing “the people” of different regions, including those of Santiago, as united against politicians, corruption, and inequality. If tweets demanding that Piñera resign or that Chile has awoken are any indication, Chileans from all over the 2600 mile long coastline are coming together with a common message, that they are united against the inequalities they have faced for the last 30 years.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed