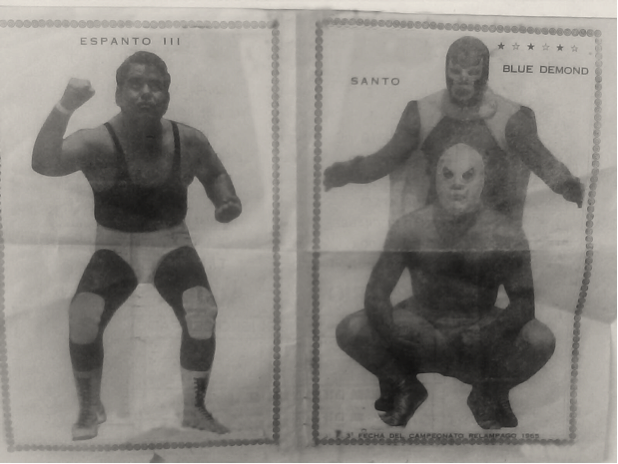

As part of this increased visibility of Mexican wrestling in the 1950s, luchadores began traveling throughout Latin America putting on events. Huracán Ramirez and Rayo de Jalisco were among those who spent time in Bolivia. They also trained new wrestlers in the cities they visited. Some early Bolivian wrestlers included: Mr. Atlas, Principe [The Prince], SI Montes, Medico Loco [Crazy Doctor], and Diablo Rojo [Red Devil].

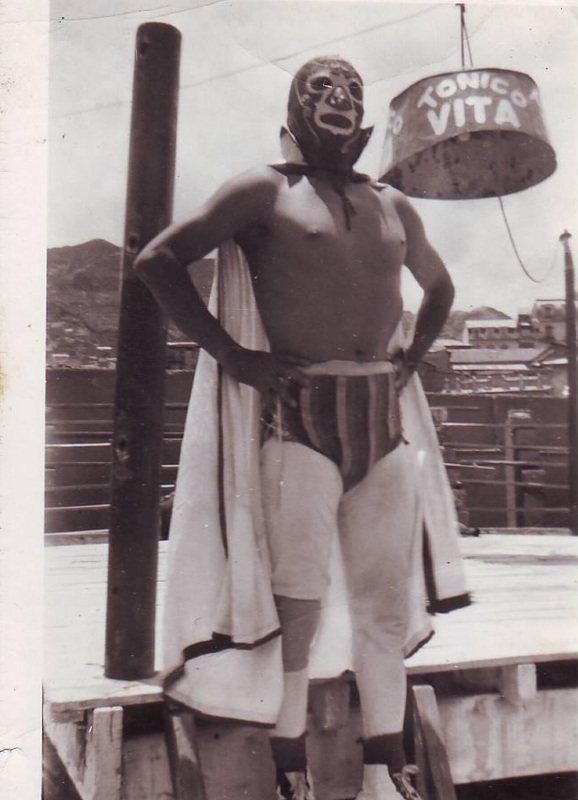

During the 1960s lucha libre events took place in the Perez Velasco, a commercial area just outside of central La Paz, popular among working class and middle class people. Luchadores usually wrestled in a makeshift ring and set up seating in a fútbol field. The costumes during this time were not particularly flashy and almost everything was improvised. But by the mid-1970s, the Coliseo Olimpico [Olympic Coliseum], a 7500 seat sports arena, was built in the central neighborhood of San Pedro, leading to more visibility.

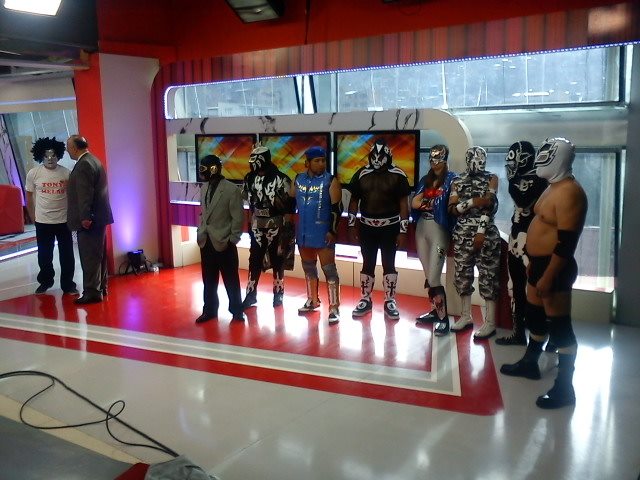

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, interest in lucha libre waned in La Paz. But in the late 1990s, a major shift occurred when Bolivian lucha libre first appeared on television. In 1998, a group of luchadores calling themselves Furia de Titanes [Fury of Titans], who were regularly putting on shows at the Coliseo Olimpico, noticed TV personality Adolfo Paco in the audience. They approached him about beginning a lucha libre program on Asociación Televisión Boliviana (ATB) channel 9, and he agreed. The program was filmed in the Coloseo de Villa Victoria, in a more peripheral neighborhood of La Paz, and was an immediate success. In addition to large television audiences, the group began attracting long lines of people hoping to see the shows taped live. Luchadores gained notoriety and were featured in local newspapers and magazines. With the addition of several corporate sponsors, luchadores earned about $200 per event.

But this success was fleeting, because not all were highly skilled, and Paco was undiscerning. This caused bitter arguments among the wrestlers. By 1999, Furia de Titanes had split in two. Those who kept the name Furia de Titanes remained on ATB, while others adopted the name Lucha de Campeones [Champions’ Wrestling] and began wrestling on the Uno network, channel 11. The rupture ultimately resulted in smaller audiences, in response to which sponsors terminated their support and thus luchadores in both groups took home significantly less pay. Lucha de Campeones, for example, offered free entrance to their live shows to encourage larger audiences, but as a result luchadores made only 250 to 350 Bolivianos ($35-50 US) per event. In the year 2000, several luchadores complained to Paco that they had never received the health insurance he had promised them. Paco ignored their requests and in retaliation, the luchadores refused to put on their event the next Sunday. They never appeared on television again. However, the end of lucha libre on Bolivian television was quickly followed by the beginning of what might be considered the current era of Bolivian lucha libre, which includes a number of groups in La Paz: Titanes del Ring, LIDER, and Super Catch, among them. Each of these groups also include "cholitas luchadoras," otherwise known as "cholitas luchadoras" [fighting cholitas].

RSS Feed

RSS Feed