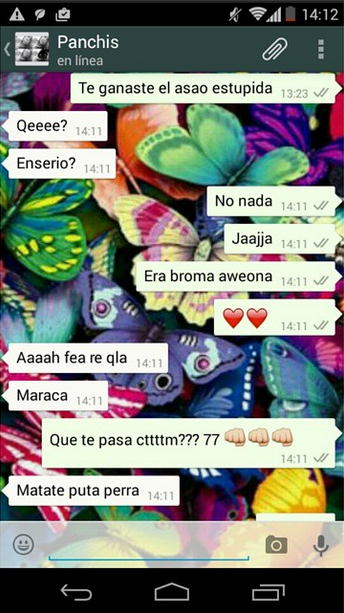

“What are you protesting?” I asked, and he pulled out his cracked Samsung Galaxy to show me. He opened Whatsapp and handed me the phone, where I read a brief manifesto in opposition to the construction of a parking lot for Bolivian trucks in Arica. “They’re going to spend 3.2 million dollars on a parking lot! And not for Chileans. For Bolivians. Do you think Bolivia has parking lots for Chilean vehicles? Or are there parking lots for us in Argentina and Colombia? No! With that money they could build homes, they could feed how many families for a year, they could fix the roads.”

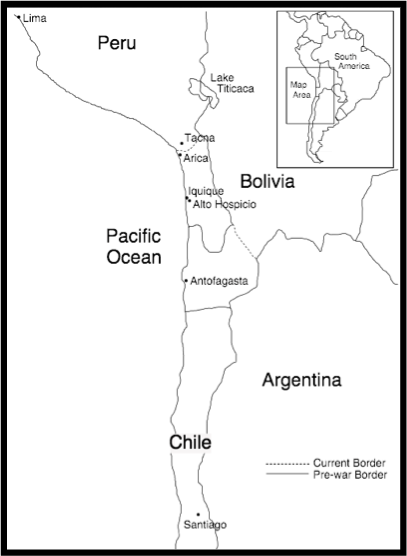

Though a parking lot for Bolivian trucks may seem like a silly issue (and a strange one to those unfamiliar with Bolivian/Chilean politics), it cuts to the heart of much deeper issues of nationalism. The two countries are currently waiting for International Court of Justice at The Hague to decide if they will consider Bolivia’s claim to renegotiate coastal access, which was lost in the War of the Pacific in the late 1800s (see my Primer on the Bolivian-Chilean Maritime Conflict). Bolivia claims that, through they ceded the coastline in a 1904 treaty, Chile is obligated to negotiate coastal access based on Chile’s offers to sea access long after the treaty was enforced (see article in The Economist).

While on the surface this is a dispute about trade and more than a century’s worth of lost GDP (not to mention the copper fields Bolivia lost in the war, which currently make up more than 30% of Chile’s export market). There are deeply nationalistic emotions that arise in these debates as well. Even for lower middle class Bolivians and Chileans—the type of people who would see little to no change in economic terms—are deeply invested in these issues. Many Bolivians see Chileans as arrogant local imperialists, publishing books such as Chile Depredador [Chile, the Predator]. Many Chileans, particularly in the northern region near the border with Bolivia, see Bolivians as backwards and uneducated, looking to get ahead by taking advantage of Chile’s resources, either by immigrating to work or trying to take a coastline that is rightfully Chilean. While for a few, solidarity across borders relies on class (see my blog on The Border: A view from Facebook), the grand majority of these national citizens have internalized their nationalism to the extent that their own lack of benefits from the arrangement and the similarities between lower middle class citizens on both sides of the border are simply overlooked.

This is particularly perplexing, given that northerners’ relationship with nationalism is rarely straightforward. Regional affiliation is usually much more important than national, as many feel disenfranchised from national politics and overlooked by the national government who simply extracts resources and money from the northern region’s copper mines, while leaving the people without social services. Yet there is strong identification with Chileanness when related to cultural forms such as food, sport, and heritage. This may be largly thanks to the process of “Chileanization” enacted in the territory when it was transferred to Chilean control in 1883. To mitigate resentment towards the military and new nation as a whole, the Chilean government launched a projects aimed at incorporating the northern population into the nation-state through religion and education for both children and adults, with mestizaje and modernization at the core of the country’s nationalist discourse.

Even today, discourses of modernity undergird the tensions between Chilean and Bolivian citizens. The conflation of nation, modernity, and race means that for northern Chileans, they represent modern mestizo subjects, while Bolivians are poor, traditional, and indigenous (which is particularly amplified by Bolivia’s recent symbolic valorization of indigeneity under Evo Morales and the MAS government).

The border dispute, for these citizens that stand little chance of material benefit or loss from a renegotiation, is important because it cuts to the root of self-understanding. To cede a border to Bolivia would mean defeat by a country and people who not only are behind in terms of modernization, but use that as an excuse to extract resources that rightfully belong to Chileans (there are certainly parallels here with discourses about Mexican and Central American immigrants to the United States). For Bolivians, Chile’s unwillingness to open negotiations is simply evidence that the nation and its residents remain unrepentant (and at times racist) thieves.

So then, why is a parking lot so important? Not only, as Andres pointed out could that money, taken from Chilean taxes (and thus rightfully belonging to Chileans), be used for something to benefit Chileans, but ceding something to Bolivians admits that perhaps there is a need for negotiation. And those negotiations are not only about access to maritime trade, but are about what it means to be a modern mestizo citizen.

This belonging was closely associated with conceptions of social and economic class, which were almost always highlighted, claiming solidarity with working class and non-cosmopolitan lifestyle. At times this even led to cross-border identifications in which perceptions of common class and proletariat ideals superseded national identification. Similarly, differences in race and particularly indigeneity were often erased in service of highlighting a broader sense of marginality, in which most Hospiceños could claim a part, rather than compartmentalizing or hierarchizing forms of disadvantage.

Further Reading

A Primer on the Bolivian-Chilean Maritime Conflict

The Peruvian-Chilean Maritime Border: A View from Facebook

The Economist - Bolivia's Access to the Sea

The Economist - The Economics of Landlocked Countries

Lessie Jo Frazier, Salt in the Sand: Memory, Violence, and the Nation-State in Chile, 1890 to the Present (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

Cástulo Martínez, Chile Depredador (La Paz: Librería Editorial G.U.M., 2010, 3er ed).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed