Hace un mes, di una charla en la facultad de antropología en mi universidad Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile en el tema de normatividad y la estetica en las redes sociales de Alto Hospicio. Hice la charla en español, pero por supuesto organicé mis ideas primero en inglés porque la charla era basada en un capítulo de mi libro, se llama Social Media in Northern Chile, que aparecerá en 2016 con University College London Press. Después de la charla, creé pdfs de la información que presenté, con los imagines, ahora en este sitio, en español aquí y en English here.

|

I recently gave a talk in the department of anthropology at my home university Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile about normativity and aesthetics as they appear on social media in Alto Hospicio. The talk was in Spanish, but I of course organized my thoughts in English first, particularly since it was based in party by a chapter of my forthcoming book, Social Media in Northern Chile (with University College London Press). After the presentation I created some pdfs of the talk, complete with all the images that accompany it, which can now be found in English here and in español aquí.

Hace un mes, di una charla en la facultad de antropología en mi universidad Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile en el tema de normatividad y la estetica en las redes sociales de Alto Hospicio. Hice la charla en español, pero por supuesto organicé mis ideas primero en inglés porque la charla era basada en un capítulo de mi libro, se llama Social Media in Northern Chile, que aparecerá en 2016 con University College London Press. Después de la charla, creé pdfs de la información que presenté, con los imagines, ahora en este sitio, en español aquí y en English here.

0 Comments

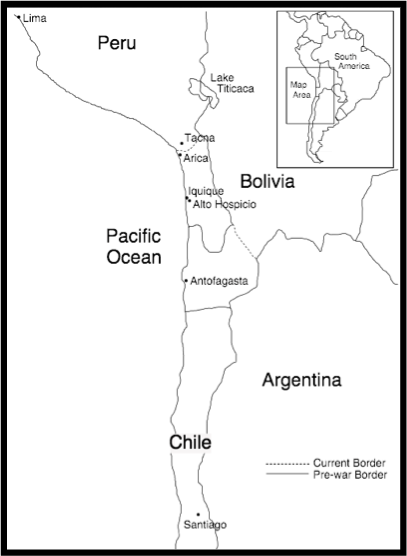

“I joined a protest group!” Andres proclaimed proudly, knowing that I tend to be a loud proponent of the right of individuals to shake things up with collective action. “What are you protesting?” I asked, and he pulled out his cracked Samsung Galaxy to show me. He opened Whatsapp and handed me the phone, where I read a brief manifesto in opposition to the construction of a parking lot for Bolivian trucks in Arica. “They’re going to spend 3.2 million dollars on a parking lot! And not for Chileans. For Bolivians. Do you think Bolivia has parking lots for Chilean vehicles? Or are there parking lots for us in Argentina and Colombia? No! With that money they could build homes, they could feed how many families for a year, they could fix the roads.” Though a parking lot for Bolivian trucks may seem like a silly issue (and a strange one to those unfamiliar with Bolivian/Chilean politics), it cuts to the heart of much deeper issues of nationalism. The two countries are currently waiting for International Court of Justice at The Hague to decide if they will consider Bolivia’s claim to renegotiate coastal access, which was lost in the War of the Pacific in the late 1800s (see my Primer on the Bolivian-Chilean Maritime Conflict). Bolivia claims that, through they ceded the coastline in a 1904 treaty, Chile is obligated to negotiate coastal access based on Chile’s offers to sea access long after the treaty was enforced (see article in The Economist). While on the surface this is a dispute about trade and more than a century’s worth of lost GDP (not to mention the copper fields Bolivia lost in the war, which currently make up more than 30% of Chile’s export market). There are deeply nationalistic emotions that arise in these debates as well. Even for lower middle class Bolivians and Chileans—the type of people who would see little to no change in economic terms—are deeply invested in these issues. Many Bolivians see Chileans as arrogant local imperialists, publishing books such as Chile Depredador [Chile, the Predator]. Many Chileans, particularly in the northern region near the border with Bolivia, see Bolivians as backwards and uneducated, looking to get ahead by taking advantage of Chile’s resources, either by immigrating to work or trying to take a coastline that is rightfully Chilean. While for a few, solidarity across borders relies on class (see my blog on The Border: A view from Facebook), the grand majority of these national citizens have internalized their nationalism to the extent that their own lack of benefits from the arrangement and the similarities between lower middle class citizens on both sides of the border are simply overlooked. This is particularly perplexing, given that northerners’ relationship with nationalism is rarely straightforward. Regional affiliation is usually much more important than national, as many feel disenfranchised from national politics and overlooked by the national government who simply extracts resources and money from the northern region’s copper mines, while leaving the people without social services. Yet there is strong identification with Chileanness when related to cultural forms such as food, sport, and heritage. This may be largly thanks to the process of “Chileanization” enacted in the territory when it was transferred to Chilean control in 1883. To mitigate resentment towards the military and new nation as a whole, the Chilean government launched a projects aimed at incorporating the northern population into the nation-state through religion and education for both children and adults, with mestizaje and modernization at the core of the country’s nationalist discourse. Even today, discourses of modernity undergird the tensions between Chilean and Bolivian citizens. The conflation of nation, modernity, and race means that for northern Chileans, they represent modern mestizo subjects, while Bolivians are poor, traditional, and indigenous (which is particularly amplified by Bolivia’s recent symbolic valorization of indigeneity under Evo Morales and the MAS government). The border dispute, for these citizens that stand little chance of material benefit or loss from a renegotiation, is important because it cuts to the root of self-understanding. To cede a border to Bolivia would mean defeat by a country and people who not only are behind in terms of modernization, but use that as an excuse to extract resources that rightfully belong to Chileans (there are certainly parallels here with discourses about Mexican and Central American immigrants to the United States). For Bolivians, Chile’s unwillingness to open negotiations is simply evidence that the nation and its residents remain unrepentant (and at times racist) thieves. So then, why is a parking lot so important? Not only, as Andres pointed out could that money, taken from Chilean taxes (and thus rightfully belonging to Chileans), be used for something to benefit Chileans, but ceding something to Bolivians admits that perhaps there is a need for negotiation. And those negotiations are not only about access to maritime trade, but are about what it means to be a modern mestizo citizen. This belonging was closely associated with conceptions of social and economic class, which were almost always highlighted, claiming solidarity with working class and non-cosmopolitan lifestyle. At times this even led to cross-border identifications in which perceptions of common class and proletariat ideals superseded national identification. Similarly, differences in race and particularly indigeneity were often erased in service of highlighting a broader sense of marginality, in which most Hospiceños could claim a part, rather than compartmentalizing or hierarchizing forms of disadvantage. Further Reading A Primer on the Bolivian-Chilean Maritime Conflict The Peruvian-Chilean Maritime Border: A View from Facebook The Economist - Bolivia's Access to the Sea The Economist - The Economics of Landlocked Countries Lessie Jo Frazier, Salt in the Sand: Memory, Violence, and the Nation-State in Chile, 1890 to the Present (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007). Cástulo Martínez, Chile Depredador (La Paz: Librería Editorial G.U.M., 2010, 3er ed). I recently wrote about the ways that northern Chileans express normativity on social media, using Kermit the Frog and contrasts between “Expected” and “Reality” memes as examples. But perhaps what demonstrates a desire for normativity even further is the way many individuals in Alto Hospicio express self-deprecation.

read the rest of this entry on the WHY WE POST blog This fieldnote has also been posted on the WHY WE POST blog at University College London For the first year of my fieldwork, I lived in Alto Hospicio, Chile, a city considered marginal and home to the working poor (as the US class system would call them). I spent the year chatting with neighbors in my large apartment building, kicking balls back to children playing in the street, shopping at the local markets and grocery stores, buying completo hot dogs from food vendors, walking along the dusty streets, and taking the public bus to and from Iquique. Now, for my last few months of fieldwork, I am living in Iquique, the larger port city, just 10 km down the 600 m high hill that creates a barrier between the two cities.

read the rest of this entry on the WHY WE POST blog As I recover from my latest South America induced “stomach thing” I’m reminded how caught up the body becomes in ethnographic research. Research on the Body This was explicit in my research on lucha libre. The final chapter of my PhD dissertation carries the subtitle, Embodied Autoethnography. My body was a key form of data collection in that research. Following scholars such as Paul Stoller (1997), Heather Levi (2008), and Loic Wacquant (2004), using the body in research, often in painful and trying ways, gives insight into the corporeal understandings of the individuals with whom we do research. Indeed, incorporating my own body, and merging the “intelligible and the sensible” (Stoller 1997:xv), seemed especially important in wrestling, given Barthes’s contention that it is “in the body of the wrestler that we find the first key to the contest” (2000:17). I write in my methods chapter At times I felt alienated from a body that just would not cooperate…My body felt fragmented during these moments... Rather than my body feeling like a unified whole, I experienced it as fragmented; hands and legs working independently, rather than together in a fluid motion. My mind became slightly detached from my body parts, and only upon being able to do the llaves without thinking did I finally feel my mind and all the body parts were completely reunited. When I quickly and easily executed a llave correctly, it just felt “natural.” I was not overly aware of where my hands and legs were placed or at what moment I twisted my back. Both my feelings of inadequacy and conversely authenticity were connected to my body. When my body “functioned,” I barely noticed it. When it did not naturally move the way I wished, whether in training, performances, or standing in the background in television promotions, I was aware of it as a fragmented entity. As Wacquant writes of boxing, “To say that pugilism is a body-centered universe is an understatement” (1995:66). A boxer or wrestler “is” their body (Oates 1987:5). And because wrestlers are portraying characters and telling stories through their bodies, this is even more true. It is the body that can either betray or grant authenticity to the wrestler. Body and (Environmental) Health But even in less explicitly body-centered research, the body is always a tool through which ethnographic research is conducted. The body is by definition (within currently paradigmatic constraints of time and space) where the researcher is. Usually in ethnographic research, this is in “the field.” Though this field may be close or far from home, things like the sickness I was experiencing until yesterday, undoubtedly affect research. Every time I’ve had a “stomach thing” in South America, I’ve learned a bit more about myself and about my research. From parasites, to what I swear must have been Typhoid, to this more recent “regular old diarrhea” one learns about public restrooms (which countries generally have toilet paper and which don’t, which ones you have to pay for and which you don’t) and where to find them (you’d think the giant fancy department stores would, but at least the supermarkets, malls, and movie theaters usually do). One learns about the way one is treated when they feel sick. Some places people are sympathetic. Some they are not. Some insist that you should see a doctor and take medicine. Others believe a bit of soup or tea should make everything better. Some charge you for everything. Others do not. Some places require prescriptions. Others do not. I remember during a particularly long and bad bout of something in Bolivia, almost exactly 3 years ago (I remember because it was during Oruro’s carnaval), I had a persistent flu-like sickness. I remember complaining to a friend in New York via google chat. “Just take a nice hot bath” she told me. I didn’t respond because that suggestion annoyed me. There were so many levels of my life that she just wasn’t understanding. My “shower” at the time was an electric shower head positioned over a drain in the center of the bathroom floor. A bath was not going to happen. Hot was also not so likely to happen. Electric showerheads come in a variety of qualities. The good ones are good. Nice hot water comes out and lasts at least 5 minutes so you can actually wash everything you’d like to. But even these never seem to be powerful enough to heat the whole bathroom, so you’re still left shivering. And then there are the bad ones—ones like that which occupied my bathroom at this time. They electrocute you when you turn them off. Or sometimes start spewing sparks. Sometimes they only get luke-warm. Sometimes they just decide not to produce any warm water at all. And that might actually be preferable to the ones that purposefully trick you with about twenty seconds of warm water—just enough time to lather the shampoo in your hair—before they go cold for good. And others tease you with two-second alterations between pleasantly hot and scream-inducing cold. All this in a place that’s average annual temperature is 46 F. Temperature itself perhaps deserves it’s own section, but I’ll be brief. One learns what it is to never stop shivering. One learns from cold showers in some places, and endlessly sweaty nights in others. One forgets what rain feels like on the face, and gets excited for the once or twice yearly sprinkle in the middle of the Atacama. Other anthropologists learn to arrange alternative transportation in case of cloud burst. Sunscreen before I walk out the door has become a way of life. I could go on, but I’ll leave it at that. Health and bodily comfort are often the subjects of anthropological research, but I’m not sure we as often consider the health and comfort of the anthropologist in a serious way. Perhaps anthropologists fear this will be misconstrued as complaining. Most anthropologists experience such bodily discomfort, and to make too big a deal of it might put them off by downplaying their own experiences. But I think paying attention to these issues actually tells us quite a bit about our research. You Are What You Eat Art from Hawk Krall Embarrassingly, food is probably the thing that for me has the biggest emotional impact. On one hand because we as humans (at least in almost every place I’ve ever visited) associate so much comfort, nostalgia, and pleasure with food. Most people in the world eat every day. And those with the resources to do so, usually try to make this into a pleasureful event. Sometimes it works out and you really love the food in the field site (ie salteñas). Other times it’s not go great, but you are in a cosmopolitan place with restaurants or supermarkets that provide sufficient options when you miss something special. Other times this isn’t the case (what I would give for sour cream or soft goat cheese…). But moreso than the availability of “special food treats,” the daily routine of eating can be a slow form of torture. Chilean food is such a case. For various reasons, I have spent most of my time here living with families, and this allows me less freedom in terms of my eating habits than I would like. Most days I’m somewhat obligated to eat a breakfast of bread, a lunch of some sort of refined grain (pasta or rice, and of course bread on the side) and some sort of fried meat (chicken, fish, pork, or beef). A few sliced tomatoes on the side is about as much vegetable as one gets. Most sauces come with chopped up hot dogs. Dinner also consists of bread with cheese and processed sandwich meat. Snacks are usually fried potatoes covered with meat, onions and fried eggs. I’d much prefer a nice salad with a bit of couscous. If given the choice, I’d go for never eating bread again over eating it at every meal. But for me, the frustration is not just about the taste. It’s about the way my body feels. I am bloated and lethargic constantly. After lunch, I can barely stay awake. More often than not I take a nap in the hot afternoon. And this is the really embarrassing part—I hate what it does to my appearance. As much as I try to exercise (something deserving of it’s own post), it is difficult, and that combined with the near impossibility of finding ways to eat healthy things (I mean, most restaurants don’t even serve water. Choices are artificially flavored juices or soft drinks), I develop a bit of a body issue. After a few weeks, my clothes fit tighter. I notice my cheeks being puffier. And yes, it’s vain, but I think to myself at times, “is fieldwork worth the weight gain?” Of course, this tells me something about the field—a place where calling someone “gordito” is much more a term of endearment than anything else. I’m constantly told I’m anorexic (and believe me, by most US health standards, I’m slightly overweight). Perceptions of health are different here, as are perceptions of taste (if it’s not overly salty or sugary to my palate, it’s ‘tasteless,’ if it’s got a bit of kick to me, it’s unfathomably spicy). And at the worst of times, these incongruences of food ideology affect my mentality to the point of feeling trapped and depressed. Conclusion: Why Even Internet Research is Never Disembodied

I am not the first to suggest that these issues are important to ethnography. More than 20 years ago, Lock described the body as a mediator between the self and the world, suggesting this should be central to anthropology (1993:133). But now doing research on “online” activity one might think the body has less of an impact. Yet I argue that what makes this research truly ethnographic is precisely the way that the body comes to bear on it. Knowing what I know, eating northern Chilean food day in and out, I understand a bit more the ways that body image and naming practices like “gordo” and “flaca” function. Thus the particular styles of selfies and Facebook nicknames make more sense to me. I find deeper meaning in Instagram pictures of food. And representations of normativity make more sense. In the end, most days, it is worth it. All the sunburns, dog bites, rabies shots, altitude sickness, hangovers, earthquakes…and the $15 hour long massages, beach trips, and delicious salteñas and completos. But ethnographic research is always a balance. One has to remember who they are, because often (at least for me), losing myself in the field results in pretty seriously negative emotional states. And sometimes, a girl just wants a freaking arugula salad! For more on embodied research, see my archives on the Body. References Levi, Heather 2008 The World of Lucha Libre: Secrets, Revelations, and Mexican National Identity. Durham: Duke University Press. Lock, Margaret 1993 Cultivating the Body: Anthropology and Epistemologies of Bodily Practice and Knoweldge. Annual Review of Anthropology 22:133-155. Stoller, Paul 1997 Sensuous Scholarship. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press. Wacquant, Loïc 1995 Pugs at Work: Bodily Capital and Bodily Labour Among Professional Boxers. Body and Society 1(1):65-93. A lot of what has been in these fieldnotes lately has come from drafts of chapters that will eventually (in January 2016) become my book about social media in Alto Hospicio. I've been out of the field for 5 months and writing profusely. But tomorrow, I return. I'll still be writing chapters, and then editing the complete draft while in the field, but in a lot of ways, returning to the field represents a complete shift of mindset. Suddenly writing doesn't feel like my job. I don't "go to work." Rather, I go to the kitchen table and open my laptop. Or who knows if I will even have a table. It may be sit on the bed or on the floor and open my laptop. Fortunately, I decided some time ago, that finishing any major work shall be rewarded with a massage at Hotel Europa in La Paz.

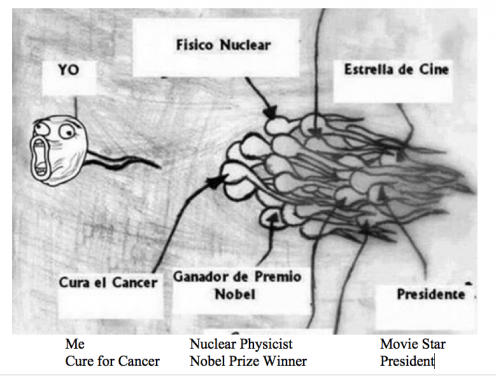

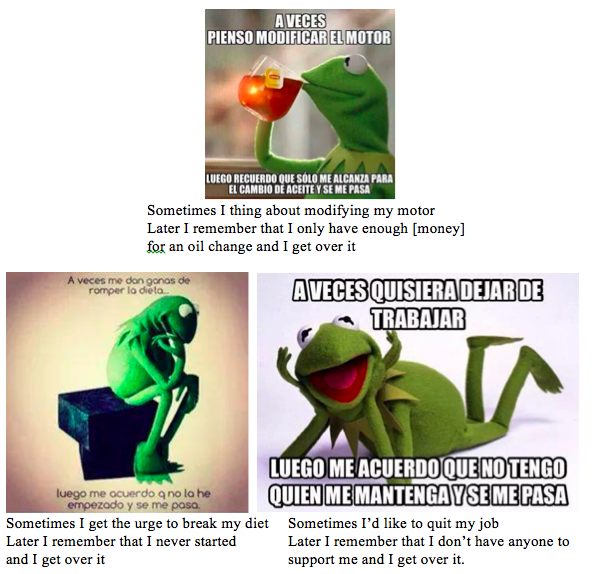

It's not standard practice, but both this project and the research that led to my PhD have happened in this way. I've been in and out of the field, and end up writing significant portions of the ethnography while in the field. For me this has been helpful. When you need to check a fact, you text or visit a friend. When you need a little more information, it only takes a few hours to set up a short interview. While it might be harder to get into the headspace of writing while in the field, it has its advantages. So, I'm not sure what will end up in these fieldnotes for the next few months (until I move to Santiago in June for the rest of my postdoc residency), but it will certainly reflect, in its own way, the actual space in which I'm writing. And I suppose that's one thing I appreciate about anthropology. That's not something to be overcome but something to learn from. As many entries in the blog affirm, local cultural aspects are often reflected or made even more visual on social media. As I have written before of my fieldsite, there is a certain normativity that pervades social life. Material goods such as homes, clothing, electronics, and even food all fall within an “acceptable” range of normality. No one is trying to keep up with Joneses, because there’s no need. Instead the Joneses and the Smiths and the Rodriguezes and the Correas all outwardly exhibit pretty much the same level of consumerism. Work and salary similarly fall within a circumscribed set of opportunities, and because there is little market for advanced degrees, technical education or a 2 year post-secondary degree is usually the highest one will achieve academically. This acceptance of normativity is apparent on social media as well. One particularly amusing example of this type of acceptance is especially apparent from a certain style of meme that overwhelmed Facebook in October of 2014. These “Rana René” (Kermit the Frog, in English) memes expressed a sense of abandoned aspirations. In these memes, the frog expresses desire for something—a better physique, nicer material goods, a better family- or love-life—but concludes that it is unlikely to happen, and that “se me pasa,” “I get over it.” Similarly, during June and July of 2014 a common form of meme contrasted the expected with reality. The example below demonstrates the “expected” man at the beach—one who looks like a model, with a fit body, tan skin, and picturesque background. The “reality” shows a man who is out of shape, lighter skinned, and on a beach populated by other people and structures. It does not portray the sort of serene, dreamlike setting of the “expected.” In others, the “expected” would portray equally “ideal” settings, people, clothing, parties, architecture, or romantic situations. The reality would always humorously demonstrate something more mundane, or even disastrous. These memes became so ubiquitous that they were even used as inspiration for advertising, as for the dessert brand below. For me, these correspondences between social media and social life reinforce the assertion by the Global Social Media Impact Study that this type of research must combine online work with grounded ethnography in the fieldsite. These posts could have caught my eye had I never set foot in northern Chile, but knowing what I know about what the place and people look like, how they act, and what the desires and aspirations are for individuals, I understand the importance of these posts as expressing the normativity that is so important to the social fabric of the community.

this fieldnote has also been posted on the WHY WE POST blog at University College London As I begin to write my book about social media in Northern Chile, it’s great to see little insights emerge. One of the first of these insights is that interaction is essential to the ways people in my fieldsite use social networking sites. Facebook and Twitter are the most widely used, with 95% of people using Facebook (82% daily), and 77% using Whatsapp with frequency. But with other sites or applications, use falls off drastically. The next two most popular forms of social media are Twitter and Instagram which are used by 30% and 22% of those surveyed respectively.

So what makes Facebook so popular but not Twitter? My first reaction was that Twitter doesn’t have the visual component that Facebook does. This was partially based on the fact that many of my informants told me that they find Twitter boring. Yet Instagram is even less well-used than Twitter. And as I began looking more closely at the specific ways people use Facebook and Twitter, I began to see why they feel this way. read the rest of this entry on the WHY WE POST blog I am something of a suspicious character in Alto Hospicio. First, I visibly stand out. As a very light skinned person of Polish, German, and English ancestry, I simply look very different from most of the residents of Alto Hospicio who are some combination of Spanish, Indigenous Aymara, Quechua, or Mapuche, Afrocaribbean, and/or Chinese ancestry. I am catcalled quite often, even while walking to the supermarket midday. These yells usually reference the fact that I am visibly different. “Gringa,” “blanca,” [whitey] and even “extranjera” [foreigner] are the most usual shouts. I hear. Even in less harassing ways, I’ve been pointed out on the street, as happened my first week in Alto Hospicio, walking along the commercial center a woman stopped in front of me simply to tell me “You look North American!” scurrying away before I could respond. maybe I look too much like her? Beyond the striking impression of my physical appearance, I was untrustworthy as a single woman. Having no family in the area, not to mention a male partner or children was often a red flag for people. Even though many people I met had left family behind in other countries or regions of Chile when migrating to the area, they usually moved with a least one family member or friend. In a lot of ways, my solitariness kept me solitary.

As I got to know people, at times I felt I was being given a test. A colleague at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile had connected me with some politically active students in Alto Hospicio, and they invited me to help put up posters for a candidate for local representative before the elections in November 2013. I met Juan in the evening, outside one of the local schools where we made small talk before they others arrived. He asked me about my opinions on the Occupy Movement in the United States, and I spoke frankly, though keeping in mind his connections to Chilean Student movements. We continued talking about US politics and he asked if I had been very involved during my time in graduate school in Washington, DC. He asked about my support for President Barak Obama. And he asked very detailed questions about who I worked for, where funding for the research came from, and to what institutions the results would be reported. Eventually the other poster hangers arrived and we walked a few blocks to the home of his friend, where we were to mix up the paste for the hangings. As he introduced me to the group, he explained that I was “a trusted friend.” So I had passed the test. Other tests of my trustworthiness took much longer. The first person I got to know outside of my apartment complex was Miguel, the administrator for the Alto Hospicio group I first joined on Facebook. Yet, it took over two months of online conversations before we met in person. Our chats at first were about the project, then about anthropology in general, while I asked him about his job at a mine in the altiplano and about his family. Later we conversed about television shows, movies, sports, and other hobbies. Eventually he told me funny stories about what his friends had done while drunk. I tried to reciprocate and realized my friends were far less rambunctious than his. Eventually, he invited me out with a group of friends to a dance bar in Iquique, and later I became friendly with his sister Lucia and her husband, often being invited to eat lunch in their home. Eventually one afternoon, sipping strawberry-flavored soda and finishing the noodles and tuna on my plate, Lucia asked Miguel how we met. He launched into a long story of seeing my post on the Facebook group site and being suspicious of it. He clicked on my Facebook profile and thought “What is a gringa like this doing in Alto Hospicio?” But his curiosity prevailed and he engaged me in conversation. As he recounted the story to his sister he eventually arrived at the night we had gone to the dance bar. “I was nervous standing outside the apartment, because I didn’t know what to expect. We had talked enough that I was pretty sure she was a real person, but I was still nervous. I thought maybe she wasn’t real. Maybe it was a fake profile. But then I saw her walking toward me and I just remember being really relieved.” In Northern Chile, most families have the radio on in the home at least 12 hours a day. The radio plays on public transportation busses, private cars, taxis, restaurants, and in service businesses like copy shops and food stores. Older residents report that music has been ever-present this way as long as they can remember. When a song they dislike begins to play they may change the radio station, but they quickly find something more to their taste. Younger people, however, are pickier. They like many genres and bands that are not played on the radio. They usually dislike Cumbia music (local to the Andes) and Reggaeton (a global form of club music that mixes dance and reggae rhythms), which are the primary songs featured on the radio. For that reason, many younger people prefer to play music with their mobile phone and computer. In fact, this is one of the only ways to select music as the only other place to get music is from vendors at the local market which sell illegally copied cds (called "piratas"-pirates). These radios are becoming less prevalent in homes in Alto Hospicio as computers and smartphones are more often the devices used to play music. Using these devices, they usually simply search for a song on Youtube. They turn up the speakers as high as possible and and enjoy this self selected music. They rarely pay attention to the video, because to them it is simply a byproduct of the important part--music. Though a few young people report having Soundcloud accounts, on my survey of 100 residents in the city, only 1 mentioned any music-related social media activity other than using Youtube. Not only do these people use Youtube to listen to music, they also post the links on their Facebook page in order to share the songs with their friends, but also send audio files recorded on their phones through Whatsapp and even use Youtube to capture songs in order to set them as the background music to their Tumblr blogs. In essence, what the radio once was--an omnipresent passive form of listening to music has been transformed into an active, yet still omnipresent, form of music listening using Youtube in combination with different devices and social media forms. |

themes

All

archives

August 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed