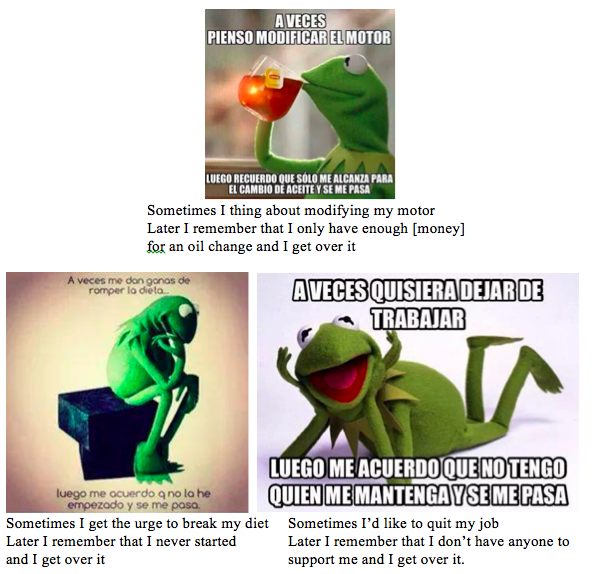

One particularly amusing example of this type of acceptance is especially apparent from a certain style of meme that overwhelmed Facebook in October of 2014. These “Rana René” (Kermit the Frog, in English) memes expressed a sense of abandoned aspirations. In these memes, the frog expresses desire for something—a better physique, nicer material goods, a better family- or love-life—but concludes that it is unlikely to happen, and that “se me pasa,” “I get over it.”

|

As many entries in the blog affirm, local cultural aspects are often reflected or made even more visual on social media. As I have written before of my fieldsite, there is a certain normativity that pervades social life. Material goods such as homes, clothing, electronics, and even food all fall within an “acceptable” range of normality. No one is trying to keep up with Joneses, because there’s no need. Instead the Joneses and the Smiths and the Rodriguezes and the Correas all outwardly exhibit pretty much the same level of consumerism. Work and salary similarly fall within a circumscribed set of opportunities, and because there is little market for advanced degrees, technical education or a 2 year post-secondary degree is usually the highest one will achieve academically. This acceptance of normativity is apparent on social media as well. One particularly amusing example of this type of acceptance is especially apparent from a certain style of meme that overwhelmed Facebook in October of 2014. These “Rana René” (Kermit the Frog, in English) memes expressed a sense of abandoned aspirations. In these memes, the frog expresses desire for something—a better physique, nicer material goods, a better family- or love-life—but concludes that it is unlikely to happen, and that “se me pasa,” “I get over it.” Similarly, during June and July of 2014 a common form of meme contrasted the expected with reality. The example below demonstrates the “expected” man at the beach—one who looks like a model, with a fit body, tan skin, and picturesque background. The “reality” shows a man who is out of shape, lighter skinned, and on a beach populated by other people and structures. It does not portray the sort of serene, dreamlike setting of the “expected.” In others, the “expected” would portray equally “ideal” settings, people, clothing, parties, architecture, or romantic situations. The reality would always humorously demonstrate something more mundane, or even disastrous. These memes became so ubiquitous that they were even used as inspiration for advertising, as for the dessert brand below. For me, these correspondences between social media and social life reinforce the assertion by the Global Social Media Impact Study that this type of research must combine online work with grounded ethnography in the fieldsite. These posts could have caught my eye had I never set foot in northern Chile, but knowing what I know about what the place and people look like, how they act, and what the desires and aspirations are for individuals, I understand the importance of these posts as expressing the normativity that is so important to the social fabric of the community.

0 Comments

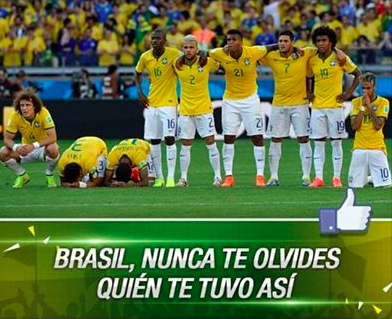

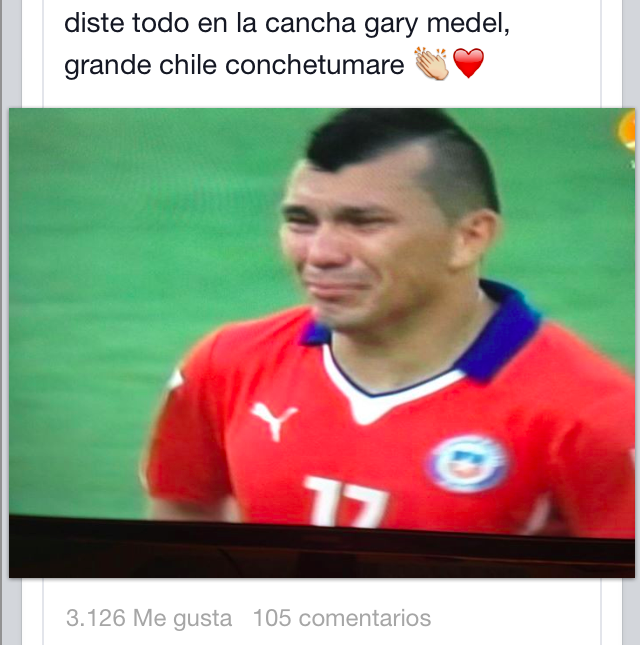

A lot of my friends in North America were rooting for Brazil in the World Cup. As a newly adopted Chilena, it annoyed me a bit. But I also never had anything against Brazil, except that they are far from an underdog, and I generally root for teams like Ghana and Costa Rica. I think for anthropologists in particular Brazil is the land of Nancy Scheper-Hughes’s Death Without Weeping, and Donna Goldstein’s “Interracial” Sex and Racial Democracy: Twin Concepts? Though we know a true post-racial state doesn’t exist, Brazil captures our imaginations: beautiful beaches, beautiful people who at least marginally have attempted to overcome the institutionalized forms of racism we in the northern half of America are still struggling with. It is developed enough to be enticing, yet still retains a sense of chaotic charms that makes it seem like a place that is ethnographically enticing. For non-anthropologists from North America, it’s all about beaches, brothels, carnival, samba, and futball*. An anthropologist friend commented on the Brazil v The Netherlands game for third place via Facebook: “Why is everybody hating on Brazil so bad? A colonizing nation kicked a neo-colonized nation's ass. And got most of Latin America, aka the neo-colonized neighbors, to cheer about this. Helloooo, false consciousness????” This confusion I think is reasonable and common for people in North America. And I am no expert on futball fandom in South America, but I’ve now seen two separate World Cup cycles from this half of America (one from Lima, Peru and one from here in Northern Chile) Being an anthropologist, I’ve noted certain things. Also, I’m going on three years around these parts and I know some things about international relations. So here goes… Brazilian futball jerseys were not a hot commodity in Chile. That empty space is where the red Chilean jerseys had been First, at least in the Andes, Brazil retains it’s “far away paradise” image. People with money go to Rio for vacation, spend their time on the beach, eating tasty things, staring at hot people, dancing Samba, possibly partying at Carnival, and maybe even going to a brothel. For others who are not as well off, it is a mystical land that is close enough to dream about but not quite reach (at least for now). Yet, part of that partially obtainable dream is Brazil’s economy. Brazil’s economy ranks seventh in the world by both Gross Domestic Product and by Purchasing Power Parity. They fall behind the United States, China, Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. The next Latin American country on the (GDP) list is Mexico, which ranks 14th, and the next South American country is Argentina which ranks 26 (and then Chile at 36). In essence, for my friends in Northen Chile, Brazil might as well be Miami—in fact Chileans don’t even need a visa to enter the US). For others, like Bolivians, Brazil may technically be far easier to enter than the United States, but exchange rates are so unfavorable to the boliviano that it would be difficult for a middle class family to afford vacationing there. Essentially, Brazil is closer, but their economic position is much closer to North America and Europe than their South American neighbors. But even if we believe Lukács that all relations are structured by the condition of capitalism (and I’ll leave that up to you to decide), these relations run much deeper than simple exchange rates. Brazil for reasons economic and otherwise often has an excellent national team. This is partially why North Americans even notice that they exist. When’s the last time any North American tuned into a Bolivian game? Or can even find Bolivia on a map for that matter? But the fact that Brazil consistently fields a good team means they get international attention. These economic and futball success factors are indeed a large part of why Brazil was chosen to host the World Cup. But this futball success also means that they usually beat their neighbors at the game that is most important to most fans. Chile, in particular, has been eliminated from the World Cup by Brazil in 2014, 2010, 1998, and 1962. That is every single time they have ever made it out of the group stage. Just (literally) bringing the Brazilian team to it’s knees this time around was a source of national pride. Brazil has also won 4 of the last 6 Copa America championships. In high school sports, they would be the fancy private school that hires university coaches and always makes it to the State Final. I think it’s also worth mentioning that this phenomenon extends to Argentina as well. Though unstable, their economy (currently ranked 26th in GDP) is still above Chile’s and Peru’s, and certainly Bolivia’s. Two Chilean friends who recently traveled to Buenos Aires for vacation recounted to me how their expectations of destitution and poverty were entirely blown away. “The people are still partying. And the drinks weren’t that cheap!” they told me. Again, similar to Brazil, Argentina is a futball powerhouse. They have qualified in every World Cup for the last 40 years, and only once have not made it out of the group stage. They have played in the final game in four of the last 10 Copa America tournaments. They are also home to the most visible and recognizable South American futball club, the Boca Jrs. And they have Messi (who is often considered arrogant and dismissive of fans). In fact, one Bolivian fan told me “The Argentinos are individualistic. They don’t work as a team, but try to be the star like Messi, the worst arrogant one.” Again, we’re talking private school here. But possibly more importantly, Argentina is a “natural rival” of Chile (and Brazil too). They have had territory disputes. And according to at least one Chilean, “they laughed at our loss [to Brazil].” A Bolivian woman reflected general South American stereotypes of the country: “Argentines are snooty. They think they’re gods. Go ahead and cry Argentinos!” These feelings are obviously not homogenous. One miner who watched the game while at work told me that bets among coworkers were even for Germany and for Argentina. And there are plenty of fans who think that “If you’re from South America you should always support our neighboring country, just as Europeans support Germany. It’s a shame.” But the point here is that while people may have personal reasons to support Argentina or Brazil, or may feel a sense of South American unity, there are also many structural reasons South Americans do not support these teams. Chilean miners calmly watch the World Cup final. Photo by Jair Correa. In relation to my friend’s Facebook question, I think it’s important to realize that while colonialism certainly shaped the form of today’s nation-states and alliances to a great extent, this is not the full story. Just as assumptions that South Americans were less civilized than their European colonizers, it would be incredibly Eurocentric to believe that some sense of historical unity against Europe would trump the present day tensions between South American citizens. History is important to them, but so are their present relationships to their material conditions of existence. From a global perspective, South America might not be the most sought after school district, but there are still a few kids who always have the latest Air Jordans. *Yes, I know this is more commonly spelled football, fútbol, or soccer. But a Spanish-speaking friend recently misspelled the word this way, and I think it's useful for North American Spanglish speakers like myself, who need to avoid confusion with "American Football" and not alienate non-North-Americans (or Aussies or Kiwis) who might not be keen on the word soccer. So there you have it. Spread the word! See my other blogs on the World Cup: The World Cup on Social Media Worldwide Seeing Red: Watching the World Cup in Northern Chile Part of the Red Sea: Watching the World Cup in Northern Chile Tears for the Red Sea: Watching Chile Lose in the World Cup Goldstein, Donna 1999 “Interracial” Sex and Racial Democracy in Brazil: Twin Concepts? American Anthropologist 101(3):563-578. Scheper-Hughes, Nancy1992 Death Without Weeping : the Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil. Berkeley: University of California Press. I wrote recently about the ways Chileans were watching and reacting to their team in the World Cup (both here and here). Essentially I described the way their behaviors, both on the street and on social networking sites violated the norms I have observed for nine months. While people are often ambivalent about citizenship—including both politics and belonging (see various definitions of “citizenship” including Goldberg 2002:271, Hansen and Stepputat 2006:296, Moodie 2006, Ong 2004, Richardson 1998, Stychin 1998)—when it comes to the national fútbol team, people very visually support them, decorating their homes, donning red clothing or Chilean flags, and posting wildly on Facebook, even the people who usually post very little content online. Yet, a winning national team can easily produce such a response. The 2014 Olympics, in which the Chileans fielded only two athletes—both skiers—provide an excellent counter example. Coverage of the games was hard to find, even on the nightly news, and I didn’t know a single person who knew when the Olympic games were scheduled, let alone planned to watch. On the other hand, the national fútbol team was impossible to ignore. The supermarkets and home improvement store were covered in promotional products. Corner tiendas were suddenly filled with flag themed hats, banners, and noisemakers, and on game day, at least half of the people I passed on the street were clad in red, after the team’s uniforms. Facebook was filled with funny memes relating to the team before the game, during play with nervous statements and goal celebrations, and after with photos of people celebrating in the street. There was clearly excitement about the team’s chances. Excitement over the World Cup was not at all about being part of a world event, but was an expression of national pride and focused on the Marea Roja’s potential to come out on top. So, then, I wondered what would happen when the team lost. I hoped, of course, that wouldn’t actually happen. That they would fulfill that potential and defeat every opponent they encountered. Unfortunately, last Saturday in a nail-biting game against Brazil, in which the home team was literally brought to their knees, the Chilean team lost. As the game ended with Gary Medel crying on screen, I expected complaints from fans. Perhaps they would blame the referees. Perhaps particular Brazilian players would be singled out for exaggerated trips or other unfair play. Maybe the coach, Jorge Sampaoli would be chastised. Or possibly, even, certain Chilean players would be blamed for mistakes. "Brazil, never forget who had you like this" But what I found was a great outpouring of pride. “They left everything on the field,” countless memes proclaimed. Other variations included “Proud to be Chilean” “They gave everything. Thank you men. Chile is grand!” “Thanks Chilean [team] for leaving Chileans with a proud name.” “We lost but I’m happy about the last match. Chile gave everything that they could. They beat Australia, the put the fear in Holland, they put Spain on the airplane home, and they had Brazil on their knees. I love you Chile. Conchatumareeeeee” Gary Medel, who cried, was hailed as a “great great warrior.” Though I expected the typically machista northern Chileans would poke fun at his emotional outpouring, I saw no joking about him crying. Plenty of memes included pictures of his face distorted and moist with tears, but the accompanying texts were ones of pride. He posted one such picture on his own Facebook page with the text “The tears are for all of you.” This photo was shared without negative comment by six of my Facebook friends. One popular meme even depicted him with the presidential sash. Another photo shared by a neighbor depicted the whole team walking off the field with Medel shedding tears in the center. “Seeing this photo gives me great pain. Chile is grand!” Drawing on Bernett (1966) and Riordan (1977), Joseph Alter observes that athletes are often “made into a symbol who unambiguously stands for his or her country” (1994:557) in a way that is divorced from Politics with a capital P and works at the popular political level (Rowe 1999). Athletes easily become national icons because they occupy the position of fantasy figures and are divorced from the economic infrastructure (Alter 1994). Sports can ideologically reach communities in ways that politicians and government agencies cannot (Levermore 2008:184). Cho calls the “nationalist sentiment or ideology” created and perpetuated through sport, “sporting nationalism,” and suggests that unlike hegemonic forms of nationalism such as government propaganda, this form fosters “an emotional, expressive attachment…[which] often elicits voluntary patriotism” (2009:349). Gary Medel indeed is an excellent example of the ways an athlete may become even more iconic in their moments of defeat, when their emotions both reflect those of their fans, and are reproduced on television and social media in a way that I would describe as simulacramous (see Deleuze and Guattari 1987—and yes, I did just invent the world “simulacra-mous”). Northern Chileans still maintain that they are forgotten by national politics and leaders. Their “national pride” is not one of blind adherence to national logics, agendas, or belonging. Rather the underdog status of the Marea Roja worked in parallel with Hospiceños underdog status within the nation. Just as they proclaimed during the recent earthquake that “Hospicio is Chile too,” with the national team’s successes and even close loss, it was as if they claimed “Chile is a formidable fútbol nation too!” "[Brazil] won the game. [Chile] won the respect of the world." See my other blogs on the World Cup:

The World Cup on Social Media Worldwide Seeing Red: Watching the World Cup in Northern Chile Part of the Red Sea: Watching the World Cup in Northern Chile Where is the South American Futball Unity? Alter, Joseph 1994 Somatic Nationalism: Indian Wrestling and Militant Hinduism. Modern Asian Studies 28(3):557-588. Bernett, H. 1966 Nationalsozalistische Leibserziehung Schorndorf bei Stuttgart: Verlag Karl Hofmann. Cho, Younghan 2009 Unfolding Sporting Nationalism in South Korean Media Representations of the 1968, 1984 and 2000 Olympics. Media, Culture, and Society 31(3): 347–364. Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari 1987 A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Brian Massumi, trans. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.Dibbits 1986 Goldberg, David Theo 2002 The Racial State. Malden: Blackwell Publishers. Hansen, Thomas Blom and Finn Stepputat 2006 Sovereignty Revisited. Annual Review of Anthropology 35:295-315. Levermore, R. 2004 Sport’s Role in Constructing the “Inter-state” Worldview. In Sport and International Relations: An Emerging Relationship. R. Levermore and A. Budd, eds. pp. 16–30 London and New York: Routledge. Moodie, Ellen 2005 Microbus Crashes and Coca-Cola Cash: The Value of Death in “Free-Market” El Salvador. American Ethnologist 33(1):63-80. Ong, Aihwa 2004 Cultural Citizenship as Subject Making: Immigrants Negotiate Racial and Cultural Boundaries in the United States. In Life in America: Identity and Everyday Experience. Lee D. Baker, ed. Pp.156-178. Malden, CT:Blackwell. Richardson, Diane 1998 Sexuality and Citizenship. Sociology 32:83-100. Riordan, J. 1977 Sport and Soviet Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Rowe, David 1999 Sport, Culture, and the Media: The Unruly Trinity. Buckingham: Open Univeristy Press. Stychin, Carl Frederick 1998 A Nation By Rights: National Cultures, Sexual Identity Politics, and the Discourse of Rights. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. This weekend I presented a paper at the Royal Anthropological Institute's conference on Anthropology and Photography, titled #Instaterremoto: Tracing Crisis through Instagram Photography. As part of the conference I was given the opportunity to showcase my own photography, and exhibited twelve photos under the same title. Here I reproduce that exhibit, which can also be found at the RAI's Flickr feed here. On the night of 1 April 2014, Alto Hospicio suffered an 8.2 earthquake. The city was without power and water for several days and many were left homeless. Because I am researching social media usage in the city, I have paid particular attention to the photos that (usually young) residents have uploaded to Facebook and Instagram. I began adding my own images to these websites with similar hashtags to contribute to the body of imagery by residents who were were many times calling for more attention and help from the Chilean national government. In many ways, the people of Alto Hospicio felt forgotten, and were using social media to speak to whoever would listen. I took these photographs, featured here, in solidarity with others who were using their smartphone cameras to claim visibility and call for attention to the disaster. The text of my paper presentation at RAI will be posted soon. Until then, here is the narrative of my experience of the earthquake. part one part two part three part four part five On April 3rd, I was awoken by the heat of direct sunlight in my tent. For the second night I had barely slept, with tremors reminding me that the earth was still moving it's plates every few hours. Though it certainly felt less scary to be close to the ground and with nothing but a thin layer of fabric capable of falling on me, the tremors were still startling enough to cause momentary heart racing. I opened up the tent door, hoping to let in some cooler air, and was greeted by Nicole's father. A few others were already up and about, and Nicole's mother had just returned to the camp with all the bread she could find. She handed out pieces and started the camp stove to make coffee. As I was sipping some black coffee for which I desperately wanted sugar, Alex stumbled out of his tent, also expelled by the heat. As he ate bread and drank coffee he spoke to his mother on the phone, who was urging him to come to her house in Arica, where less destruction had occurred. But radio reports the day before had declared the road between Arica and Alto Hospicio closed. Alex called his uncle to find out more. His uncle informed him that the roads had been reopened for non-commercial traffic. Alex was convinced. However, there was still the question of getting enough gas to make the four hour drive. The Copec station along route 16 in Alto Hospicio was only dispensing gas by 1 liter increments to people on foot. So we drove further up the road to the edge of the city where another Copec station was closed to all but emergency vehicles. Alex decided he would try the station on the other side of town, but it was closed completely. Another call to Alex's uncle, and his report was that the gas station in Pozo Almonte, 40 miles to the East, was open as normal. How the uncle was an expert on transportation, I didn't know, but when Alex decided he was at least going to drive to Pozo to see the situation, and invited me along, I realized there wasn't much reason to stay in a precarious apartment in a city with no electricity or water. So I packed a bag quickly, getting out of the apartment before another aftershock and we set off. Indeed, gas was being sold normally in Pozo Almonte, and we filled up the tank, then took a 6 hour drive to Arica. It is normally much quicker, but there was indeed quite a bit of fallen rock along the road. For much of the drive, the road is bordered on the East with high hills. During the earthquake, much of the rock that makes up these hills had come loose and fallen, in both big bolder sized pieces and smaller, but equally as unnavigatable basketball sized pieces. lights shone as we drove into Arica As the sun was setting at 8pm, we finally arrived to Arica, a town flickering with light, and people living normally. We went to a pizza place and ordered a pie, then to a botilleria where we bought a 6 pack of beer. Alex paid for both using his debit card, which had been impossible in Alto Hospicio for the last two days. His mother's house did not have electricity restored yet, nor water, but it was nice enough just being able to buy takeout dinner as if things were normal. Indeed, the people of Arica didn't seem phased at all. The chaos of Alto Hospicio never ensued, and they were practically living life as if the earthquake had been a minor hiccup.

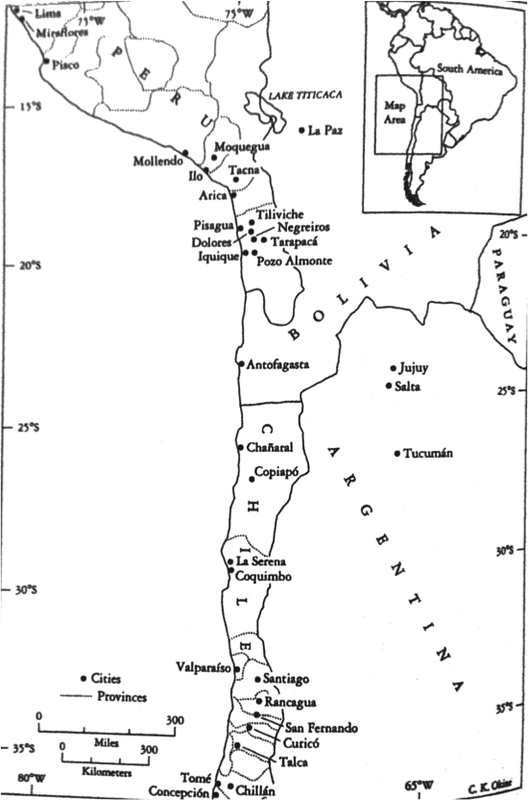

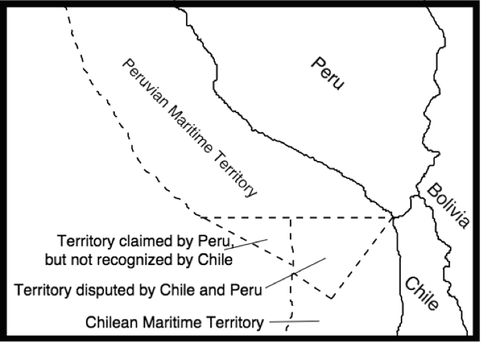

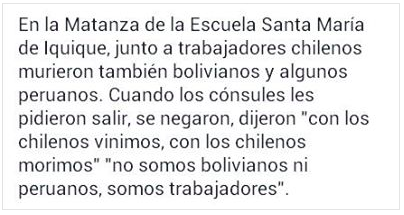

Chile gained independence from Spain in 1810, and it's northern border was defined near the city of Taltal. When Peru gained independence 1821 it's southern border was near the present city of Tocopilla (meaning that Arica and Iquique were also within Peru's boundaries). Further to the South, the territory of Antofagasta gained independence with Bolivia in 1825. map from A History of Chile, 1808-2002 by Simon Collier and Willaim F. Slater (p 130) The border between Bolivia and Chile ran through the Atacama Desert, and was somewhat undefined, because neither country had much vested interest there. However, the natural fertilizer, sodium nitrate (salitre), was discovered in the desert in the 1830s, and attracted many foreign investors to the area. Nearby, Iquique-still a part of Peru-grew as a cultural and financial center because of increased mining business. The city was one of the first in the region to have electricity in homes and businesses. The Teatro Municiapal (Municipal Theater) of Iquique was built to showcase plays and musical acts. A railway station was built by John Thomas North, and Englishman known as the “King of Nitrate." But this attention and growth caused some diplomatic tensions. With the nitrate boom, both Chile and Bolivia took an interest in the wealth they could acquire from this area and attempted to re-negotiate the border. In 1874 President Tomás Frías Ametller of Bolivia and Frederico Errázuriz Zañartu of Chile agreed that the border would be set at 24° S. Bolivia would retain the area around Antofagasta, but would not tax the Chilean company that was already operating in the area. This arrangement worked for a short time, but when the Hilarión Daza became president of Bolivia in 1876, he began heavily taxing the Chilean company. Angry over the breached agreement, the media and popular sectors called for the newly elected Chilean president Aníbal Pinto to take the territory. He ordered the army to seize Antofagasta in February 1879. Bolivians suggest this was successful because most of their armed forces were celebrating Carnaval at the time. After two weeks of Chilean occupation of Antofagasta, Bolivia declared war. Because of a “secret” treaty signed in 1873 (meaning it was not publicized, but most politicians in the region knew of it), Peru was obligated to come to Bolivia’s aid. At first, Peruvian president Manuel Prado tried to mediate, but the general population of Chile protested, calling for further action and persuaded the president to declare was on both Bolivia and Peru in April 1879. Hoping to create a buffer zone so that Bolivia would not be able to inch into Chilean territory again, the Chilean Navy set out to control maritime access further north. They blockaded Iquique then continued further North to Callao. By 1880, Chilean forces were trying to capture Arica, another strategic port north of Iquique and eventually were successful. Eventually, the Chilean Navy made it all the way north to Lima in January 1881, where they demanded the cession of the Peruvian regions Tarapacá, Arica, and Tacna, but Peruvian president Nicolás Piérola did not cede. Peru was still occupied in July 1882 when they won the battle of La Concepción, causing public sentiment in Chile to change. Finally, Chilean government proposed to occupy Tacna and Arica for ten years and retain Tarapacá indefinitely. In 1884 Chile signed an “indefinite truce” with Bolivia, granting them only temporary occupation of the Bolivian coastline. Yet, this area still remains under Chilean control, as do Arica, and Iquique (despite current Bolivian president Evo Morales’s appeals to the United Nations). Further Reading The Peruvian-Chilean Maritime Border: A View from Facebook They Paved (Nationalist) Paradise to put up a Parking Lot: Cultural Dimensions of the Bolivian-Chilean Maritime Conflict this fieldnote has also been posted on the WHY WE POST blog at University College London When Daniel Miller came to visit my fieldsite in Northern Chile a few weeks ago, I took him on a walking tour of the city. He had just arrived from his own fieldsite in Trinidad, and as we walked he kept remarked that two places are quite different. They share certain aspects: warmth, nearby beaches, revealing clothing, and gated homes. Yet, he told me that compared to the razor wire or broken glass-topped fences in Trinidad, these just didn’t seem as intimidating. Similarly, we discussed the ubiquity of car alarms as the continuously sounded that evening as we sat in my apartment. “Are they really protecting anything if one goes off every three minutes?” I asked. read the rest of this entry on the WHY WE POST blog for a primer on the maritime conflicts between Bolivia, Chile, and Peru that exist as a legacy of The War of the Pacific at the end of the 19th century, see my post here. I often get the sense here in Northern Chile that politically people are very polarized. Not in the sense that they are either quite liberal or quite conservative, but rather in the sense that they are either very politically active, or have entirely written off politics as something that doesn’t not pertain to their lives. One night while gathering to hang up posters for Raquel’s Regional Representative campaign, Juan told me that Chile has a “lost generation” when it comes to politics. Those that came of age during the Pinochet regime were often too afraid or too disorganized to see themselves as a political force in any way. “We are still rebuilding” he told me. Juan, Raquel, and some of their other friends are certainly making an effort to rebuild political participation among Chile’s young adults. They run for city office, they organize protests, art exhibits, performances, and observances to promote things like indigenous rights, and stand in opposition to things like neoliberal multinational capitalism. But then there are the others like my neighbor Sarita who told me before the recent election that she wouldn’t vote because it doesn’t really matter who wins. “No one pay attention to us in the North, anyway.” Similarly, when I asked my friend Alex if he’d like to watch the movie NO with me, he declined. The film is the tale of a 1988 referendum to decide Pinochet’s permanence in power. It follows the opposition—the “No” vote, and their advertising campaign that wins the election. Alex said he had no interest because he didn’t really understand politics. “People of my parents’ and grandparents’ age, they lived through it. But I don’t really know the history, so movies like this…well, I’d rather watch The Walking Dead or something.” And yet, today, people from both sides of this (a)political divide seemed to have something in common. At least they did as viewed from Facebook activity. Today was historic for maritime relations between Chile and Peru (and to an extent, Bolivia). The area in which Alto Hospicio lies was Peruvian at the time of independence. However, during the War of the Pacific between 1879 and 1884, Peru lost the land to Chile. The final borders drawn during the peace accords at the end of the war are still somewhat disputed, particularly by Bolivia which lost all of their coastline. Today, the Hague decided upon a dispute between Chile and Peru, not over coastline or cities, but over sea territory. Granting Peru more sea territory, but keeping rich fishing areas in Chilean control, the international court redrew the maritime border (BBC's coverage). I am not one to assess or even speculate on the consequences of this decision politically or in terms of economics and trade. However, as an ethnographer, when I got on the bus from Alto Hospicio to Iquique this morning there was no doubt everyone was listening to the radio report live from the Netherlands that played over the vehicle’s sound system. Facebook was also abuzz with references to the trial. Both politically active and somewhat apolitical Chilean users asserted a similar view, but in different ways. Both groups seemed to be communicating that though perhaps the Chilean and Peruvian governments were in a dispute, the people were not. Some friends did admit to me that they felt the decision to cede some water area to Peru was unfair. But they also felt that avoiding conflict was important. Many said that the decision was irrelevant because economic gain from the sea territory only ends up in the hands of seven families of the oligarchy. But these nuanced opinions were not published on Facebook either through original writing or links to online sources. Instead, solidarity between Peruvians and Chileans overwhelming dominated the Facebook posts from my friends. On the political side, Raquel and her friend Marcelo both shared a piece of text essentially thanking Peruvians and Bolivians for standing with Chileans during the Santa Maria School Massacre in Iquique in 1907. In the Santa Maria School Massacre of Iquique, together with Chilean workers, Bolivians and some Peruvians also died. When the consuls asked them to leave, they denied saying “We came with the Chileans and we will die with the Chileans. We are not Bolivians or Peruvians, we are workers. A band known for promoting indigenous rights and political content in their songs posted a long piece of text from which I will draw out some relevant parts: Patriots, fellow Chileans…Why do we not go to war against Monsanto? Why not fight to recover copper from your country? Why do you not wage war on Spanish companies that rob us when we pay for light and water? Why were you not in solidarity with artisanal fishermen when the Chilean government perpetually delivered the sea to the seven richest families?...Chileans and Peruvians stop being so easily swayed by media sensationalism of the bourgeois press. We should continue fighting together against those that make our lives impossible! Most people who usually stay away from political discussion stuck to humor. Many memes declared something along the lines of “The sea is neither Chilean nor Peruvian, it belongs to the fish!” Tell me, are we Chilean or Peruvian now? I don't know [with typical Chilean filler word], I don't know [with typical Peruvian filler word]!!! My friend Jaime asserts, “It’s so hipster to say that people shouldn’t complain about the decision of the Hague. I bet if you take the issue of sushi those assholes will start a revolution.” About those who feel an end to conflict is more important than specific borders, he implicitly suggests they stand in a privileged position (‘hipster’ being aligned with the northern hemisphere, urban culture, and detachment from the material consequences of everyday life), yet continues to make light of the situation sarcastically suggesting that what they would really care about is sushi. Peruvian friends shared the link to an article in the online magazine The Clinic, which listed "Ten Things That Perú Has Won That Hurt More Than the Decision of The Hague." Among the 10 were #2 Rich Chilean chicks prefer to summer in Mancora [Peru], and #8 Pisco-In 2013 the European Union recognized Peru's rights over the marvellous liquor." Even the Bolivians had their say through sarcasm and parody: illustration from la mala palabra revista So much bullshit with this. The half to the right for Chile. The half to the left for Peru. And the path in the middle for Bolivia!!!

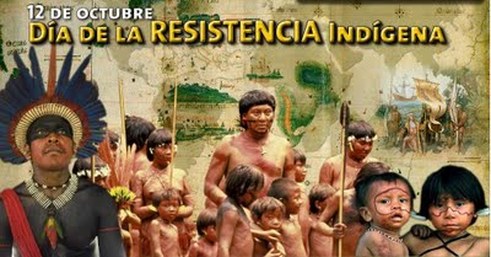

So if my friends are representative of Northern Chileans, or at least those between the ages of 20 and 40, it seems that though everyone was paying attention, no one really cared. Perhaps because this border only affects the oligarchy, or perhaps because they believe an end to dispute is more important than the ways the sea area is divided, these people express their interest by enthusiastically posting and commenting. Yet what they assert is that the outcome does not really matter. I am curious to see if in coming days more serious, nuanced, and critical discussions will take place on Facebook or on the street. But for now, people seem to be avowing “Yes, I am paying attention!” without taking sides on a matter that to most is “supposed” to be important, but in their daily lives simply doesn’t matter. Further Reading A Primer on the Bolivian-Chilean Maritime Conflict They Paved (Nationalist) Paradise: Cultural Dimensions of the Bolivian-Chilean Maritime Conflict As the AAA (American Anthropological Association) annual conference descended upon Chicago a few weeks ago, the blogosphere and twittersphere (are those words?) were abuzz with everything even remotely anthropological. My favorite post of all, not surprisingly came from Savage Minds, and was titled “Conference Chic, or, How to Dress Like an Anthropologist.” anthropologists buzzing around the hotel lobby at AAA Now, this is not the first time I’ve scooped Savage Minds (the post in question)...But back in February 2012, I wrote a fieldnote titled “How to Dress like a Tattoo Artist.” Therein, I analyzed, discussed, and lightheartedly critiqued the ways my tattoo artist friends in La Paz dress. I concluded that “their bodies, in some ways more than other [people’s bodies], are obviously constructed…but though the specifics might differ, their bodies are constructed through the same processes as everyone else’s.” These processes include, as outlined by Donald Lowe (2005), the work we do, the commodities we consume, and the politics of gender and sexuality [and I would add religion, race, class, etc, etc] to which we ascribe or aspire. In other words, these bodies (all bodies) flexibly accumulate markers through consumption, production and processes of identification. And though obviously much of this works through commodified symbols, most anthropologists are aware of, if not actively critiquing, the contradictions of the capitalist system and the social problems associated with consumptive practices of the late modern era. In short, many of us would not be caught dead in the middle of an anthro conference wearing something that everyone knows was made under unfair labor conditions, mass-marketed, cost more than a day’s salary, or looks too ‘mainstream.’ Thus, the non-commodified symbols carry perhaps more weight with anthropologists than with many other groups (though even with both tattoo artists and backpackers in South America, these are incredibly important). Savage minds lists six categories of anthropological fashion/fashion concern: “anthropological” fieldsite flair, professional-but-not-too-professional balance, critique of capitalism and consumerism, career-stage, subdisciplinary distinctions, and scarves. Yes, scarves get their own category, as they well should. a colleague’s facebook post about her flight from DC to Chicago for AAAs For me, the two that most reflect what I wrote about tatuadores are fieldsite flair and the critique of consumptive practices (though I think professional balance could be a subset of this). Both are in the service of authentification, but work in different ways. Firstly, to keep in mind the problems that arise from the ubiquitous consumptive practices of late-modern capitalism is not only about acknowledging global inequalities and all of the exploitation (of people, non-human animals, and natural resources) that is necessary to produce and sustain such a system of production and consumption (and that obviously is a very important part of it), but is also about performing as a person who is concerned about these things. Because as anthropologists, at least in this century, we are concerned with issues of social justice, to be ignorant or dismissive of these problems would mark one as uncritical, and thus something of a not so great anthropologist. Thus, to dress smartly, thoughtfully, but not entirely professionally, and certainly not in a way that overtly supports unjust productive and consumptive conditions, is to perform authentication (Bucholtz and Hall 2005:500) as an anthropologist. The flair component of dress performs authentication of another requirement of anthropology: fieldwork. Because anthropology prides itself on use of ethnography, long-term engagement with a fieldsite, and integration into communities in which we study, to wear things that come from or reflect the places we work becomes an important performance as well. Of course at times these things remind us of those to whose kindness and help we owe our information and lifework. But they also are something of a symbol to show to others not only where we work, but it’s importance to us, and that yes, we actually spent enough time in the field to find a beautiful stone necklace, to acquire a beautifully embroidered blouse, or even to be given a tshirt promoting a local business. And so, in the ways we dress, anthropologists often reflect the twin pillars of anthropology: theory and practice. Savage Minds quotes Carla Jones: “I suppose it is unsurprising that anthropologists are invested in what we wear at AAA, after all this is our social community. Who better than we understand that social meaning is generated through symbols?” Like the very tattoos that tatuadores wear, some symbols are important because of the social capital they connote, rather than their economic worth (use value rather than exchange value to put things in Marx’s terms). And scarves are just important because they are awesome. I show off fieldsite flair with my bolivian necklace, and of course, it’s paired with a scarf And now, as a nod to perhaps my only consistent blog reader, I shall end with a question. What do you wear (at academic conferences or otherwise) that involves some sort of symbol? Is it conscious or ingrained that you do so? And what do you definitely not wear because of what it symbolizes? References: Bucholtz, Mary and Kira Hall 2005 Identity and Interaction: A Sociocultural Linguistic Approach. Discourse Studies 7(4-5):585-614. Lowe, Donald M. 1995 The Body in Late-Capitalist USA. Durham: Duke University Press. Further reading: Adkins, Lisa and Celia Lury 1999 The Labour of Identity: Performing Identities, Performing Economies. Economy and Society 28(4):598-614. Atluri, Tara 2009 Lighten Up?! Humour, Race, and Da Off Colour Joke of Ali G. Media, Culture, & Society 31(2):197-214 Halberstam, J. 1998 Female Masculinity. Durham: Duke University Press. Mort, Frank 1998 Cityscapes: Consumption, Masculinities and the Mapping of London since 1950. Urban Studies 35(5-6):889-907. 1995 Archaeologies of City Life: Commerical Culture, Masculinity, and Spatial Relations in 1980s London. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 13:573-590. Today is 12 of October. In the Midwest, where I went to elementary school, this is known as Columbus Day. Later, as I gained a bit more worldly perspective I came to call it Indigenous People’s Day or Genocide Day under my breath. A few days ago, I got upset when my mother, who is a second grade teacher, mentioned she had Columbus Day off—partly because it is still institutionalized and partly because she called it Columbus Day without a hint of critique. But I’ll cut her some slack. When I’m in central Illinois she usually lets me come talk to her class about colonization. And the amazing thing is, when you explain that colonization was simply a bunch of Europeans who wanted to take the resources on another continent and felt it was necessary to murder, enslave, rape, and destroy the residents of that place in the process, even 8 year olds are pretty quick to realize that this is not something to be celebrated. I arrived at the Preuniversitario where it was held around noon and was immediately asked where I’m from. I felt a little defensive and said that Raquel had invited me and hoped it would be ok if I could just stand in the back and watch. And then I realized the woman had asked me because all of the other audience members had pin on badges that announced what country they are from. Chile and Peru dominated the group of 50, but there were a few small nametag-sized Bolivian, Ecuadorian, and Colombian flags pinned to shirts as well. Unfortunately there were no United States pins on hand, but they were happy to have me. The chairs were all full, so I stood along the back and watched a slide projection on the front wall. There were pictures of Alto Hospicio and various local groups interspersed with graphical slogans such as “12 de octubre, 2013: 521 años de resistencia” [521 years of resistance] and “Por la dignidad de los pueblos americanos, 12 de octubre nada que celebrar” [For the dignity of american peoples, 12 October is nothing to celebrate]. The program began with a Chilean Cueca dance performed by two pairs adolescent boys and girls. Then the Ecuadorian woman who had greeted me earlier performed a pop song from her country. Representatives from the Colombian and Ecuadorian immigrant associations in Iquique spoke. An Afro-Peruvian woman sang two more songs, and several community figures and political candidates spoke briefly. Scattered throughout all of these various performances were discourses about the unity of the Americas against Europeans and Gringos (“that’s me!” I thought…). The Peruvian singer shouted several times over the boombox that accompanied her “America Latina es una sola!” As the last local leader was speaking, Raquel came and stood next to me at the back. She asked if I could stay for the reception afterwards because she’d like to introduce me to a few people. I accepted and met several of the people she works with at the Preuniversitario along with being coerced into eating plenty of bocadillos, ceviche, and grilled shrimp. As the reception was ending, Raquel’s friend Juan called everyone to the back room to take a photo. I lingered in the front room, but he singled me out saying “You too, Nell. You’re from the Americas. We need our representative from the United States present.” So I followed the crowd to the back, where we rearranged ourselves a number of times against a backdrop of handpainted paper flags, and finally got a decent shot (well, you can be the judge). There is certainly some multicultural pride here in Alto Hospicio, at least when it comes to public presentation. And the mix of anti-colonial and multi-cultural discourses was interesting, but not surprising given what I’ve seen here so far. But what I find most interesting is the memorialization that occurs through such events. Though the focus is on celebration and community, it is framed by this discourse of resistance to colonization and a memorialization of a past that continues to influence present events. One of the SocNet themes of focus is on the way memorialization occurs through social networks (see Shriram Venkatrama's account from India here). I’ve been keeping my eye out for Facebook pages dedicated to individuals who have died, but perhaps more important are these ways of memorializing political events and figures, not only online but in real life events, and the naming of institutions (more on that in the next post!).

|

themes

All

archives

August 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed