Today, there are four major wrestling organizations currently operating in La Paz: LIDER (Luchadores Independientes de Enorme Riesgo), LFX (Lucha Fuerza Extrema), Super Catch, and Titanes del Ring. LIDER, LFX, and Super Catch are smaller than Titanes del Ring, and only Titanes and LIDER have permanent places of performance. These two groups host foreign tourists in their El Alto performance venues each week, though Titanes del Ring boasts a much larger crowd and much larger group of travelers than LIDER. Super Catch usually produces shows in neighborhoods such as Villa Victoria (nicknamed Villa Balazos because of the frequency of shootings in the area), Villa Copacabana, or Villa Armonía—all working class neighborhoods of La Paz. However their schedule is somewhat sporadic. They have also recently opened a training program for young wrestlers that remains small. LFX is the smallest and least known of the operations with rare performances. Titanes del Ring, conversely, consistently attracts hundreds of audience members each Sunday at their show in the Multifuncional de la Ceja de El Alto (the multifunctional arena located in the Ceja market area of El Alto).

|

I was contacted late last week by a reporter for a well-respected British news outlet. He is writing a story on the cholitas luchadoras (which as I side note I'm intrigued by, because there is definitely an article from this same source for a few years ago I've referenced a few times). He asked questions on several topics, including the history of lucha libre in Bolivia. This is something about which I have found very little authoritative information. After many conflicting interviews and hours of pouring over Bolivian newspapers from the 1950s-1970s both here and in the US Library of Congress, here is what I know. You can find recent history here, and history of Bolivian lucha libre in the 1970s-1980s here. Though almost every veteran luchador in Bolivia tells the story a little differently, it was during the time of nationalism in the decade following the 1952 Revolution that lucha libre made its first appearance in Bolivia. The form of wrestling that developed in Bolivia already had a long history. Charles Wilson (1959) has traced exhibition wrestling to army men in Vermont in the early 19th century. During the civil war organized bouts became popular among Union troops. After the war, saloons in New York City began promoting matches to draw customers. By the end of the 19th century PT Barnum was using wrestling “spectaculars” in his circus. At first, wrestlers would fight untrained “marks” from the audience, but by the 1890s they began to fight trained wrestlers planted in the audience. It was then that it changed from a “contest” to a “representation of a contest.” These spectaculars were very popular and were replicated at county fairs, which eventually resulted in intercity circuits by 1908 (Wilson 1959). By the 1920s, promoters began to add gimmicks to make characters more memorable. In 1933, after character development, rules, and other conventions had been established, a promoter named Salvador Lutteroth brought exhibition wrestling to Mexico. He and his partner Francisco Ahumado set up their first wrestling event in Arena Nacional in Mexico City on September 21, 1933. The next year they began the Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre (Levi 2008:22). In the next few years, innovations in costuming, character, and technique further “Mexicanized” the genre. Levi argues that at this time the audience was likely made up of both popular classes as well as elites (2008:23). By the 1940s, lucha libre spectators were more from the popular classes, but it still retained a sense of urbanism and modernity (2008:23). In the 1950s, it began to attract a middle class audience on television, but it only remained broadcast for a few years. It was also during this time that it became a popular subject for hundreds of Mexican films (2008:23). During this era, exhibition wrestling arrived in Bolivia. Most wrestlers suggest that lucha libre was first performed in Bolivia sometime between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s, as Mexican wrestlers traveled to South America, performing and then training the first generation of Bolivian luchadores. Many of the most veteran Bolivian wrestlers who are still active in lucha libre identify these Mexican luchadores as their childhood inspiration. Rocky Aliaga, a Bolivian who currently wrestles in Spain told reporter Marizela Vazquez, “From my childhood I was fan of wrestling and what excited me most was to attend events…of Mexican characters such as Huracán Ramirez, Rayo de Jalisco, and Lizmark.” In particular, Huracán Ramirez is often mentioned as one of the most important influences. Mr. Atlas, a veteran La Paz wrestler recalls, "I started fighting when I was 13 in 1965, when the greats of Mexican wrestling arrived in La Paz. Particularly I remember Huracán Ramirez, the man who fathered me." An interview with Boliviana Euly Fernandez, the widow Huracán Ramírez Younger wrestlers, like Anarquista from Santa Cruz, also note that the reputation of lucha libre in neighboring Perú was important to the formation and popularity of Bolivian wrestling. Mexican wrestlers toured South America, but it was the periodic visits by Peruvian wrestlers to La Paz that gained a hold in the 1960s. (7-23-2011).

Today, there are four major wrestling organizations currently operating in La Paz: LIDER (Luchadores Independientes de Enorme Riesgo), LFX (Lucha Fuerza Extrema), Super Catch, and Titanes del Ring. LIDER, LFX, and Super Catch are smaller than Titanes del Ring, and only Titanes and LIDER have permanent places of performance. These two groups host foreign tourists in their El Alto performance venues each week, though Titanes del Ring boasts a much larger crowd and much larger group of travelers than LIDER. Super Catch usually produces shows in neighborhoods such as Villa Victoria (nicknamed Villa Balazos because of the frequency of shootings in the area), Villa Copacabana, or Villa Armonía—all working class neighborhoods of La Paz. However their schedule is somewhat sporadic. They have also recently opened a training program for young wrestlers that remains small. LFX is the smallest and least known of the operations with rare performances. Titanes del Ring, conversely, consistently attracts hundreds of audience members each Sunday at their show in the Multifuncional de la Ceja de El Alto (the multifunctional arena located in the Ceja market area of El Alto).

0 Comments

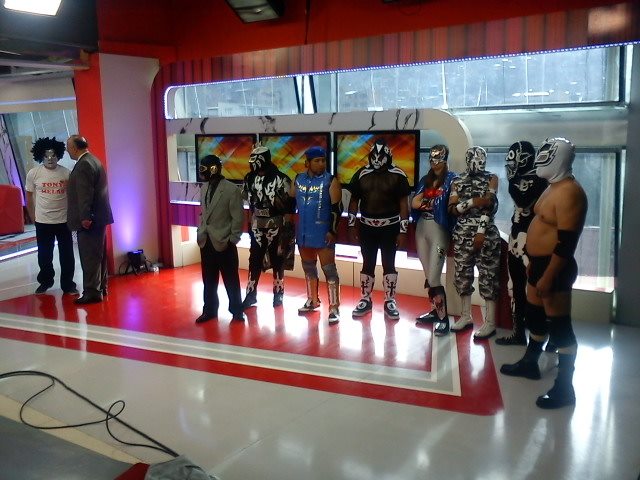

My favorite example of the ironic appreciation of lucha libre, which I saw live on Friday night, is the band Surfin Wagner. I first heard of them because the lead singer was a friend of a friend, but quickly discovered they had quite a following of Paceños. The band’s name is derived from a famous Mexican luchador, Dr. Wagner, otherwise known as Manuel González Rivera. He began wrestling in the 1960s as a rudo, but by the early 1980s—when the members of Surfin Wagner and my friends were young children—he had become a technico. In 1985 he lost his match in a well-publicized event and essentially retired. The band, like my friends who I wrote about here, creates humor using a frame shifting strategy by combining lucha libre aesthetics with surf music. The band members use lucha libre inspired names (Pedro Wagner, Médiko Loko—a misspelling of famous Mexican luchador Médico Loco, Roy Fucker—after a Japanese anime character later used in Mexican wrestling, El Momia, and Comando—both popular characters in Bolivian wrestling), and wear lucha libre head-masks along with their Hawai'ian print shirts. They describe their music as “el Garage, el punk y principalmente el Surf, siempre con un toque de sátira e ironía” [garage rock, punk, and principally surf, always with a touch of satire and irony]. The “biography” of the band on their website suggests that the band members are legitimate luchadores (again with irony), and they point out the incongruity of a surf band in a country without access to the sea. Clearly their use of the lucha libre aesthetic is meant to evoke laughter rather than contribute to a serious musical appreciation. So, over these last three posts, I've tried to give a sense that for many Paceños lucha libre in general, and the cholitas luchadoras’ participation specifically, are a light-hearted representation of Latin American culture. In a sense, lucha libre is positioned as authentically Latin American in a now-globalized world. As they combine cholas with punk culture or classic Mexican luchadores with surf rock, they reterritorialize these “traditional” icons by merging them with global symbols. When Super Catch wrestlers made appearances on morning and evening national talk shows, another kind of irony was present. Granted, Latin American talk show hosts are not known for being subtle, but the overacted excitement, fear, and horror these hosts communicated verged on the clowning Edgar was always so adamantly against. When Super Catch wrestlers made appearances on morning and evening national talk shows, another kind of irony was present. Granted, Latin American talk show hosts are not known for being subtle, but the overacted excitement, fear, and horror these hosts communicated verged on the clowning Edgar was always so adamantly against. In March and April of this year, Super Catch luchadores (including myself) appeared on the Univision morning program, Revista, five times. Though the show has four hosts, it was always Tony Melo who interviewed us, and sometimes even donned a luchador mask acting as a mark for the luchadores. The segment always featured a brawl between wrestlers, and often Tony would be pulled into the grappling. The peleas always ended with Super Catch luchadores ganging up on Tony, as he was flung around the sound stage and mock kicked after being thrown to the floor. He very much acted as the clown figure in these situations, flailing arms, and making exaggerated faces for the camera. He always wore a curly wig, and t-shirt that said “Soy No. 1.” Tony Melo is on the far right with his co-anchor. Super Catch luchadores are: Super Cuate, Big Boy, Desertor, Black Spyder, Lady Blade, Tony Montana, Gran Mortis, and Big Man In contrast, the luchadores seemed more serious. Our costumes were clearly better constructed. Our moves were more practiced and more effective in contrast to Tony’s. But much like Edgar’s worries about the cholitas luchadoras, Tony’s clownish acting gave an air of farce to the wrestling that happened on television. No luchadores ever commented on this except to roll their eyes occasionally when Tony was mentioned in the backstage area. Nor did I have a chance to ask Tony or the program producers what their intentions were with the way they presented lucha libre. But the audience for Revista is much larger and far more varied than the in-person audiences which actually attend events. There were viewers that phoned in to win free entry to the event, often saying they hailed from working class neighborhoods like Villa Armonía in La Paz or Villa Esperanza in El Alto. But this is also a television program which professional Paceños watch as they prepare in the morning for work as managers in banks, universities, and international organizations. Thus, the fact that Tony’s acting on the program reflects the ironic appreciation of lucha libre is not surprising. Though TV interviewers always treated all the luchadores with respect, their over-acted treatment of the segments seemed to stem not only from their television personalities, but from a deeper sense of irony they were communicating to viewers.

One of the peer reviewers for my JLACA article suggested that I include more information about what “elite” Paceños think of lucha libre. I didn’t think this fit well into the article, but I do think the general public’s reactions to lucha libre are something interesting to be considered. This is part one of a short series on middle class interpretations of lucha libre. The luchadoras are “un orgullo Paceño en La Paz y El Alto” [A Paceño pride in La Paz and El Alto] David, a local LGBT activist told me. “Es una pasion de multitudes…la gente burguesa y popular” [It’s a passion of the multitudes. The elite and popular classes]. It was not exactly my experience that they were the “passion” of middle class people, but they were certainly within the realm of popular discussion topic. As I wrote about here, one night at a party I put on a pollera and braided my hair. Gonz was the only one there who knew my secret, so when Luis, shouted “Tienes que luchar! Como las cholitas en la lucha libre” I was caught off guard. Amidst much laughter we all started pretending to wrestle. To my friends at the party, the luchadoras are something of a joke that carries classed inflection. Like a monster truck rally or square dance might be viewed by urban elites in the United States, lucha libre is not disparaged outright, but seen with a certain sense of dismissal or ironic appreciation. Here they express an understanding of the preference for the genres of excess that has often been classed. As Linda Williams explains of film genres, those that have a particularly low cultural status—horror, pornography, and melodrama—are ones in which “the body of the spectator is caught up in an almost involuntary mimicry of the emotion or sensation of the body on the screen” (1991:4). These films, rather than appealing to elite classes as “high art” are seen to be for the less educated, less “cultured” masses. A luchador's son performs as "Chucky" at the 30 March 2012 Super Catch Event And indeed, lucha libre combines aspects of all three of these film types. The enacted violence of the ring reflects the gratuitous violence of horror films. The intimate contact of bodies, and sometimes explicit sexually charged scenarios can be read as pornographic (see Messner, et. al 2003, Rahilly 2005). And several scholars have pointed to the melodramatic nature of the extreme good and evil portrayed in exhibition wrestling (Jenkins 2007, Levi 2008). Thus, for many of my friends lucha libre lies squarely within the bounds of that which is not to be appreciated—at least on an artistic or serious level. However, like North American young people, young Paceños sometimes have ironic appreciation for degraded cultural symbols like lucha libre. Irony often functions as a “frame shifting” mechanism (Coulson 2001) in order to express humor. When I entered the party wearing a pollera, Gonz shouting “cholita punk” shifted the frame from the representation of cholitas as traditional and thoroughly Bolivian icons, to something integrated with the international youth culture of punk rock. Even my own laughter at wearing the pollera and braids played on the disjuncture of a U.S. gringa in clothing with cultural meaning in the Andes. And most certainly, when Luis suggested I wrestle, irony was used to disrupt the usual interpretation of a mujer de pollera. Coulson, Seana

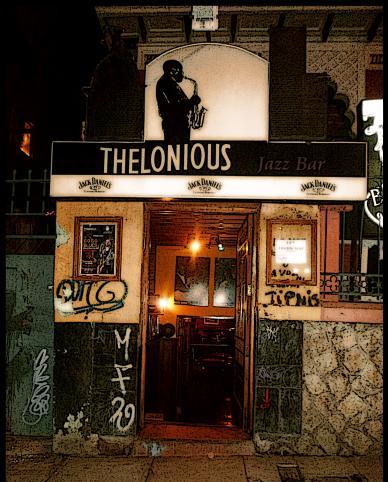

2001 Semantic Leaps: Frame-shifting and Conceptual Blending in Meaning Construction. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Jenkins, Henry 2007 The Wow Climax: Tracing the Emotional Impact of Popular Culture. New York: New York University Press. Levi, Heather 2008 The World of Lucha Libre: Secrets, Revelations, and Mexican National Identity. Durham: Duke University Press. Messner, Michael A,, Margaret Carlisle Duncan, and Cheryl Cooky 2003 Silence, Sports Bras, And Wrestling Porn : Women in Televised Sports News and Highlights Shows. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 27:38-51. Rahilly, Lucia 2005 Is RAW War?: Professional Wrestling as Popular S/M Narrative. In Steel Chair to the Head: The Pleasure and Pain of Professional Wrestling. Nicholas Sammond, ed. Durham: Duke University Press. Williams, Linda 2001 Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess. Film Quarterly 44(4):2-13. In July of 2008, after a long day of dancing to A Hawk and a Hacksaw, Icy Demons, and Animal Collective at the Pitchfork Music Festival, I found myself with some long lost friends at Belmont and Western. I hadn’t seen or talked to Ravi in years. We had dated briefly in college, but more importantly we were student government co-conspirators. He was the director of an umbrella organization for progressive student groups. I was the executive officer for Students Advocating Gender Equality. Together we led protests across campus and Chicago and tried to lobby both student government and the administration to pass resolutions condemning the occupation of Iraq. We never succeeded at that, but the “camp out” we held at the library plaza did eventually get the university to sign onto the Workers’ Rights Consortium Designated Suppliers Program. approximately the last time I had seen Ravi So five years after our graduation we sat across a table at The Hungry Brain catching up (he was about to run for a state representative spot in his home district) and waxing nostalgic (with stories one should never share about a political candidate they support). And the Hungry Brain is a lovely place. Nestled in Roscoe Village, its a cash only dive bar. The type of place I’d normally flock to. And on this particular night there was a jazz trio playing. I’m sure they were playing quite well, but at least in the back corner we occupied our laughter was the overwhelming sound. And the other patrons weren’t so keen on this. We got dirty looks often, and shhhhs a few times, so at the set break we walked around the corner to some 4 am bar that inexplicably had 3 motorcycles parked in the back room. In the intervening years I’d eventually attend summer outdoor jazz in the park type events or find myself gulping wine at Columbia Station in DC. But last night, I finally stopped into the jazz bar I’ve been walking past for 3 years. I’ve always meant to check it out, but never had a reason. When Joaquin told me he knows Pablo, the owner and suggested we go, I jumped at the chance. Thelonious is promoted as the only jazz bar in Bolivia, though I have no idea how accurate that is. In La Paz it is certainly the most well publicized, but as far as I know there could be some hidden in the back lanes of El Alto, or a thriving jazz community in Santa Cruz. Thelonius, like Hungry Brain and pretty much all bars in La Paz, is cash only. But aside from music, cash, and alcohol, my experience there was very different from the Hungry Brain. We arrived around midnight and found Pablo, his girlfriend, and another friend at a table by the door. Having arrived with Joaquin, our Colombian friend Jhon, local electronico DJ Chuck Norris, and his date, we pushed several tables together and joined Pablo and company. The Jack Daniels flowed freely and we discussed race politics in La Paz (in as lighthearted a way as we could). The conversation was filled with that distinctive Paceño laugh-a velar nasal “yaaaaaahhhhhhhh.” the flyer DJ Chuck Norris gave me that night Only at the set break was the music mentioned. Joaquin told me that the bass player (of course) was one of the best in La Paz. He then introduced me to the manager—one of the best jazz drummers in South America. I got plenty of (undeserved) Jazz street credit for being from Chicago. And our table was not unique. The overall feeling of the place was lively. People were laughing, and at times cheered and whistled for solos. The occasional drink was spilled without much notice. People danced on their way to the baño and stopped at other tables to chat on their way back. In essence, it would have been the perfect place for Ravi and I that night after Pitchfork. And perhaps this is just an isolated example, but to me it felt significant. Here in La Paz music is about enjoyment, having fun, creating an atmosphere for smiling and laughing. In Chicago, home of Green Mill, and Old Town School of Folk Music, its about connoisseurship. And this is no moral judgment on either, but to my untrained ear, I’d rather joke with Colombian Jhonny about Paceños’ laughs than quietly get lost in the beat. And to an extent I think this reflects some of the tensions in lucha libre as well. The cholitas luchadoras are there for the laughter, the smiling, the shouts, and raucousness. And luchadores like Edgar understand the importance of the audience, but see their art as something to be appreciated on an elevated level. Again there is no moral judgment here, and I think most artists of whatever sort would prefer to be appreciated for their technical ability and crafting of style—but there are definitely two different approaches to performance at play here.

_ Last week I went to Yapacaní in the Santa Cruz department to meet the godson of one of my oldest and best anthro friends. She was flying back to Denver, and I had a 20 hour bus back to La Paz, so she handed over the book she had just finished, The Glass Castle. It was far from my favorite book ever, but at the end the narrator describes a moment in which she felt as if she had arrived. I started thinking about what it might mean for an anthropologist to arrive. _Yesterday, I read over some reviewer comments on an article I am trying to publish, and felt like I was getting close. Is publishing in a well regarded journal arriving? Is getting a post-doc? Any job? Is it getting a tenure track position? Or when you finally get tenure? In the academic world, what is the moment when you feel legitimate?

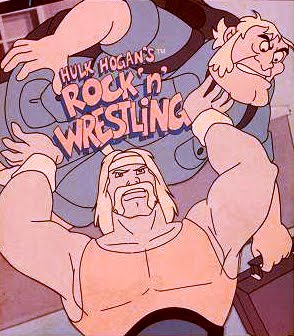

Those specific moments are probably further off for me than I’d like to think, but recently, I’ve had a few that felt like arrivals. In mid-June, I was told several times that my Spanish is “perfect.” Edwin told me for the third time last week that I don’t count as a gringa. But I think a moment that was particularly and personally an arrival for me was after getting back to La Paz last Thursday. The Tito’s guys were having a party, and I came along with some other friends. For some unknown reason, half way through the night we all ended up wearing costumes, composed of random clothing items lying around. Jack ended up wearing a nightgown and a mouse mask. One woman dressed herself as a bride, another as a bumble bee. But the hostess found the real treasure for me: a pollera. I took off my ripped jeans wore it with my plain black t shirt and my converse shoes. As I started dividing my hair into a center part, Andres started telling me I needed trenzas. “Ya estoy intentando hacerlas.” I talked to Edwin about how one attempts to sit in a pollera. I told Gonz it wasn’t poofy enough and he told me that “real” cholas wear five at a time (I think that was a bit of an exaggeration). In the ultimate statement of poetic irony, Luis--who knows nothing about my research--suggested I start wrestling as a cholita luchadora. But my favorite response was Gonz looking up from his drink and shouting “Mira, es cholita punk!” Yes, I had arrived. _ This morning several Super Catch stars went to Palenque TV (canal 48) to record some messages aimed at children. The channel is going to start airing lucha libre, under the name Tigres del Ring, and the promo spots recorded will come at the end of commercial breaks. picture from appearance on Unitel, not Palenque TV _ Palenque TV is a project of Veronica Palenque, daughter of the late Carlos Palenque Avilés. Carlos was a presidential candidate in 1989 and 1993, running for the CONDEPA (Conciencia de Patria or National Conscience) party. In 1993, he received just over 14% of the vote, putting him in second place behind Goni (who garnered about 35.5%). Perhaps more interestingly, Carlos spent his time in the 1960s singing social-protest songs and cultivating long hair. He then became part of Los Caminantes, a pop-folk group that quickly became one of the most popular bands of time in La Paz. He eventually went solo, and the Bolivian National TV station (the only TV station in Bolivia at the time), asked him to do a weekly live music show aimed at indigenous and rural-origin peoples living in La Paz. He solicited Remedios Loza, or Comadre Remedios, to be his cohost on La Tribuna Libre del Pueblo [The Community’s Open Forum]. Remedios identified more closely with indigeneity than Carlos and dressed de pollera. She and Carlos remained close, and after his death, so ran for President in his place in 1997. However, it seems that Remedios had sharp tensions with Veronica, and left the program (for more information see Moore's piece here). Veronica herself then served in the Bolivian National Congress from 1997-2000. She first formed a radio station in 2000, with the objective to continue the line of social welfare, information, education, and training that Compadre Palenque (referring to her father) left behind as his principles, precents, and ideology. “Red Palenque Comunicaciones, fue creada el años 2000, con el objetivo de continuar la línea de ayuda social, información, educación y entretenimiento que el Compadre Palenque dejara bajo sus principios, preceptos e ideología.” In 2011 Veronica began the TV station, in response to the proliferation of pain, suffering, bad news, disasters, catastrophes, and negative news usually available on television. She decided to create a channel that emphasizes fun, entertainment, laughter, joy and positive aspects of life. Veronica explained, “El control remoto tiene que convertirse, a partir de hoy, en una ‘varita mágica’ que transporte al televidente a un oasis de entretenimiento y diversión, porque aquí sólo verá felicidad” [As of today, the remote control has to become a ‘magic wand’ to transport viewers to an oasis of entertainment and fun, because we only see happiness]. _ And, then, enter the luchadores: bastians of fun, entertainment, laughter, joy, and positive aspects of life (?). We started out recording a clip where we (attempted to) say “Hola Amigitos! Somos Tigres del Ring. Pronto por Palenque TV!” in unison. We pretty much failed and ended up just saying “Hola Amigitos” together, with Luis announcing who we were and Edgar promoting the station. After our group recording, we each each recorded a short PSA style message for kids. These messages were not our own of course, but were scripted and handed to us to memorize about half an hour before recording. I am unfortunately left to talk about the scripts in a passive sort of voice, because they arrived to us on little pieces of yellow notepad, handwritten by someone other than the camera guy who passed them off. We did have to wait around for Veronica to arrive, and my previous experiences with her have shown that she is quite involved in most aspects of the station. So I would venture to say she was the source of the scripts, but I can’t say for certain. I would also guess that the handwriting was a woman’s, but I’m no expert on gendering based on script. My little script was written in Spanish as “Practicar deportes, alimentarse sanamente, y alejarse de vicios son las claves de una vida exitosa. Ustedes pueden ser heroes. Es un mensaje de Lady Blade, junta con los Tigres del Ring. Estaremos pronto por Palenque TV.” But of course Omar wanted me to do it in English (I didn’t mind), so I translated it as “Practice sports, eat healthy, and stay away from drugs are the keys to a successful life. You can be a hero! This is a message from Lady Blade and the Tigres del Ring on Palenque TV.” So yes, my little bit was chock full of certain moralizing messages that seem to conflate bodily health with some sort of emotional or social decency. And I suppose this is not surprising given the social welfare, information, education, and training espoused in the radio station’s mission statement. But what was especially interesting were the references to “our country” most of the other luchadores had in their scripts. Luis’s was the most explicit. His went something like: “To support our beautiful country, Bolivia, we need to work hard and stay healthy.” Carlos’s began with “Drugs and alcohol destroy your life! But we can be heroes for our country, Bolivia by staying fit and respecting each other.” Edgar’s concentrated on keeping Bolivia beautiful by recycling, caring for water, and not polluting. Finally SuperCuate’s was short and simple, “The values of respect, education, and consideration make us heroes for Bolivia.” This reminded me quite a bit of the “lessons” of Hulk Hogan’s Rock n’ Wrestling show from the 1980s. Indeed, US wrestling is often fraught with nationalist storylines which help to delineate heels from faces (villains from good characters). And nationalism has certainly had its place in my experiences wrestling in Bolivia. Primarily, I’ve had to walk a fine line promoting the US, but maintaining my status as a technica (good character). I wave at the kids, and they seem to love me, which helps. But when E came to visit and made an appearance as my partner on the program “La Revista," he played the rudo well, telling the Bolivians they had a lot to learn from the US where “real” wrestling takes place. _ But mostly its always struck me as strange that wrestlers, people who enter the ring and seemingly commit acts of violence, are poised as role models. As Nick Sammond writes, “Wrestling is brutal and it is carnal. It is awash in blood, sweat, and spit, and…depends on the match—the violent and sensual meeting of human flesh in the ring” (Sammond 2005:7). Is this really the way to teach values like respect, education, and consideration?”

But I suppose meeting “them” where they’re at is a viable approach. And if luchadores are icons that kids look up to, encouraging them to take care of themselves, each other, their country, and the earth isn’t all bad. Especially given the fair amount of inferiority complex some Paceños I've met have about their country, perhaps encouraging a little nationalism isn’t entirely bad (though still complicated). I was at a La Paz bar around Purim this year, and there happened to be a lot of Israelis there (because there are always a lot of Israelis in La Paz). One young man, whose English was not particularly good, was hitting on me. He told me that he was a dj and occasionally (about every 4th sentence) mentioned “I’m famous in Tel Aviv.” Eventually growing weary of this statement I told him “Well, I’m famous in La Paz.” This is not exactly true. But I find more and more that my “fame” in La Paz resembles the way I felt in the small town where I grew up. I’ve written already how I consistently run into people in the street here. But I think my day yesterday in general was a nice, comforting, and sometimes surprising indication of what I might egotistically (and not without irony) refer to as fame. I woke up and was writing a bit at home. Sharing chocolatey cereal with my roommate Thomas, when our other roommate Jack came into the room. “Anybody want to go repelling today?” Ummm…..maybe? After hearing a meager amount of details, I agreed. “But I have to go pick up my package at the post office first.” So I set off, fully expecting this to be step 1 of 7 or 8 in customs forms and bank deposits before my old jeans and sneakers would fall into my hands. There was no line to pick up international packages, and the pollera clad woman behind the window found my box quickly. She held onto my passport while I went downstairs to customs. And there in the doorway was the man who was actually quite helpful when Alé and I were attempting to get the box of tattoo needles through customs. The man walked over, took one look at me and said, “You look familiar. Have you been here before?” I explained yes, and why, and he asked “There aren’t needles in this one are there?” “No, just some old shoes of mine from the US.” He handed the box back without opening it. So I ran back upstairs, reclaimed my passport, and headed to Hotel Presidente, La Paz’s 5 star establishment. In the lobby I ran into Brian, a Death Road biking guide I’ve met a few times before. This Urban Rush business is his, and he wanted to do a soft opening to practice to asked Jack to invite some people to try it out for free. He led me to the elevator, and we went up to the 15th floor, then up some grand stairs to a restaurant that looks out over La Paz. And then finally up a small spiral staircase to a smallish room on the very top of the building. There was an open window with some scaffolding around it for harnesses. Yep. That’s where I was about to step out of. Eventually, Jack came around with some people from the bar he manages and we were all given awesome orange jumpsuits to wear and went through a little training. I, for some reason, volunteered to go first on the practice wall, and thus was first in line for going down the real thing. And so I did. 17 stories. With about 5 stories of free fall. And then they convinced me to do it face first. And that was even more awesome. So yes, I was the very first person, not employed by the company to try this all out. After my thrilling experience, I had another. Dropping off laundry. Umberto, my laundry man, always strikes up a conversation. This laundry place is nowhere remotely convenient to my new apartment, but Umberto always gives me a discount along with good stories, so I return. This time he decided not to charge me at all. “Why pay? You can pay next time.”

After that I headed over to a café to do some writing, and along the way ran into Jack and Samuel, one of the bar’s owners. Less than a block later I saw Gonz from Tito’s and explained that I had just been repelling to him. “Que Bueno!” He walked off with a “Nos vemos esta fin de semanana” and a kiss to the cheek. The rest of the day was less exciting. A bit of writing, eating dinner, hanging around the house. But its nice to live somewhere that doesn’t feel strange any more. They always warn you transportation is the most dangerous part. Its always in the movement from one place to another that the anthropologist is most vulnerable. Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo was just walking down a footpath when she fell to her death. Even more anthropologists have written on the perils of transportation in their fieldsite. Ellen Moodie writes about an bus crash in El Salvador and points out the ways global inequalities and institutions actually bore quite a bit of responsibility for a seemingly “accidental” incident. And certainly, anthropologists such as Lynn Stephen—who works with undocumented immigrants—can’t ignore the perils of transportation for such a population. But you never think it will be you who is in that crash. I suppose because the academic anthropologist is among the first-world privileged and can choose to use “safer” forms of transportation than the public busses Moodie describes. And are privileged enough to be able to obtain visas rather than illegally crossing borders (aside from Bourgeois’s famous example). And indeed, I was returning from getting my visa to remain in Bolivia. It was an annoying bureaucratic process that took far longer than it should have, but it was not impossible. And the kind (but paternalistic) Consulado kept assuring me they would give me the visa if only I could provide a little more documentation. Obtaining the visa was a vastly different experience than my middle class Bolivian friends have had when trying to get tourist visas for the U.S. And as for transportation, I decided to avoid the 30 hour, somewhat comfortable tourist bus from Lima to La Paz and opted for what I assumed to be a more posh option. Flying to Juliaca would—yes—require me to take some local busses rather than a fancy full cama option. But would also be much faster and presumably safer. Of course, this was not exactly the case. As the taxi from Puno to Desaguadero went spinning off the road and those mortal thoughts when racing through my head, I never once thought “this isn’t supposed to happen.” But I did think that later. As I reflected on the events, I couldn’t help but think of the endless stories you hear in the Andes of busses careening off the sides of cliffs. All the passengers and driver die. And they all remain nameless locals. This doesn’t happen to the tourist or anthropologist because they can afford the safer option. And that comforts us the night before we travel. We have paid our $70 rather than 120 Bs. (about $18) to travel, thus ensuring our safety. We will arrive in (relative) comfort and be happily on our way. But the truth is, there is an element of luck. Sure, it seems the more you pay the better your chances are. But things like blockades, weather, and poorly maintained roads treat us all somewhat equally. Of course, some have the luxury to avoid travel when conditions are less than perfect. Some have the luxury of flying rather than taking any ground transportation at all. But even if I had flown directly to El Alto, I would have still had the blockades on the autopista to deal with. Money and status help, but they don’t take away risk completely. And so, as I sat in the back seat of that recently-demolished taxi, and watched the Peruvian man next to me bow his head and cross himself, in a way I wished for something to thank other than luck for my survival. I had been given enough of a shake to be reminded that wealth and status can’t always protect you. I wanted something else to believe in to keep me safe. But I had nothing. And the truth was, it wasn’t even myself that I was afraid for (except maybe in the moments when I was sure I was going to freeze to death). I have lived a good life. I have done amazing things and been loved by amazing people. And my attitude toward transportation is often: I would rather die in the process of going somewhere than sit idly at home, afraid to take a risk. And I stand by that still. But I was afraid for the people I love. Perhaps I’ve just read the introduction to Culture and Truth by Renato Rosaldo (Michelle’s widower) too many times, but I didn’t want my parents, sister, colleagues, professors, and friends to wish I had never come here. To wish they had stopped me or proposed I do local research. I had no regrets. I don’t want to be the cause of regret for anyone else either. And so, having returned to La Paz, I sit in my cushy SoHocachi house, writing this on a day when all the choferes (taxi drivers, bus drivers, and voceodores) are striking and blockading the streets of La Paz. And I wonder if perhaps they don’t ask for enough. I argue with taxi drivers over the difference between 10 and 12 Bolivianos (about 30 cents) to take me home at 10pm. But that taxi driver could be keeping me out of harm. But that’s just the beginning. Perhaps better roads, more structured public transportation, more accountability. And this is starting to sound like I’m making a bigger government argument, but hell, this country has already nationalized about every industry it can get its hands on, and the Movimiento A Socialismo party is in power, so maybe that’s a moot point. A little more reliability for transportation would go a long way around here. But at least the Cebras are a start. Moodie, Ellen

2005 Microbus Crashes and Coca-Cola Cash: The Value of Death in “Free-Market” El Salvador. American Ethnologist 33(1):63-80. Rosaldo, Renato 1993 Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston: Beacon Press. Stephen, Lynn 2007 Transborder Lives: Indigenous Ozxacans in Mexico, California, and Oregon. Durham: Duke University Press. After much bureaucratic negotiating, I finally got my visa and was ready to be on my way. Rather than taking a 30 hour bus ride back to La Paz, I decided to take Amanda’s advice and fly from Lima to Juliaca (about 2 hours from the border) and then take a variety of busses back to La Paz. The trip should go something like this: 9:15-11:00-flight from Lima to Juliaca 11:15-12:15-bus from Juliaca to Puno bus terminal 1:30-3:30-bus from Puno to Desaguadero 3:30-4:00-pass through the Perú/Bolivia border at Desaguadero 4:00-5:30-minibus from the border to El Alto 5:30-6:00-minibus from El Alto to the Prado Yes, I would be back in time for Tuesday evening festivities I thought. And then there were blockades. Surprisingly, the Peruvian side was worse. This was how it actually went: I exited the plane at the Juliaca airport and stood in line for what seemed like hours to use the restroom. Once that was finally taken care of, I went outside and found a small coach-style bus bound for Puno. I took a seat behind a young Venezuelan guy who had grown up in the United States and studied “Security and Peace” in Tel Aviv. I rarely agreed with the assessments of the world he was making to the British couple in front of him. I was also lucky enough to be sitting beside a man traveling on business who kept insisting I have lunch with him. While showing me pictures of his wife. I told him I’d have to check on a bus to the border first. The bus made it to Puno easily and drove around the small town on Lake Titicaca dropping people off at their hotels. The bus terminal was the last stop and 3 of us got off, only to be told there were road blocks and busses to the border were not running. The three of us: a young Peruvian man, a middle-aged Argentinean woman, and myself, kept giving each other frustrated looks. The woman asked a taxi driver if there was any other way to go to Desaguadero. For 100 soles a piece he said he would drive us “the long way.” We haggled down to 50 each, bought some snacks and hopped in the back of the car. “The long way,” he told us, would take four hours. I ate some of my Ritz crackers and nodded off to sleep. But with the 3 of us stuffed in the back seat (one other man was in the front with the driver, apparently having contracted him earlier), the complete lack of heat in the car (like all Andean cars), and the curvy mountain roads, it was not an ideal sleeping environment. About 2 hours in, we were all awake and chatting a little. And then we rounded a corner as it started snowing. As we drove along, not far below the mountain tops (the road was at 4800 meters at this point) the snow accumulated and was beautiful. The Peruvian guy took out his cell phone and started snapping photos. I grabbed for my camera and got one of the mountain in front of us. I leaned back so the Argentinean woman (who had been stuck in the middle seat) could snap one out the window on my side. And then suddenly we slid. We crashed through 4 barrier posts. We spun in a circle 3 times. I thought to myself “is this how I’m going to die?” We fortunately (and I mean that with all the gravity the word can have) flew off the road right where we did, because there was no steep embankment. About 70% of the road in that section of the drive did have a steep descent off to the side. But we were lucky. The car hadn’t been equipped with seatbelts, but no one flew too far out of their seat. The driver’s-side window shattered, but no on was cut. The driver’s door was dented and wouldn’t open so the man in the front got out to let him climb across. The car was badly dented in several places. Two tires were completely flat. And the engine wouldn’t start. I had been sleeping on and off, but had stayed awake enough to know that it had been at least an hour driving since we passed by the last lonely home along the road. With the engine dead and the window busted, the snow and wind were coming into the car. “No, this is how people die in the Andes, I thought: Stranded, and they freeze to death.” I’ve seen the movies about plane crashes and cannibalism…. Fortunately, not long after a man in a pickup truck came driving by in the opposite direction. The Peruvian man flagged him down, and tried to negotiate some sort of transportation. The man was refusing, but even before he left, a station wagon occupied by a husband and wife drove up. With only minimal convincing they decided they would turn around and take us to Desaguadero. The taxi driver stayed with the car and we promised to send police or a tow truck his way. The four passengers piled into the back seat of the station wagon, with all of our luggage in the back. We were on our way again, much less comfortably, and much more slowly. What added to the lagging time were the several police checkpoints we had to go through. Each time, the man driving would be questioned as to why he had a license and registration for a private vehicle, but appeared to be carrying strangers. Cause let’s face it. Nobody was going to believe this gringa was in anyway related to these kind campesinos. After explaining the story, the police were always kind and let us pass. Four hours after the crash, we stopped at the final checkpoint in which another man convinced the vehicle owners to let him ride in the back end of the car for 60 km. My feet and hands were numb from the cold. My butt and thighs were numb from the position I had been sitting in, unable to move for four hours. And I was nauseous from the curvy roads and probably whiplash from the crash. The Argentinean woman had to ask twice to pull over so she could vomit. Eventually, after 6 hours in that position (making a total of 8 hours in transit) we arrived in Desaguadero. But of course, it was 7:30 pm by this time, and the border had been shut since 6pm. Alas, the 3 of us found a hospedaje with 3 beds in a room for 10 soles each. We watched some futbol, ate some chifa, and went to sleep. At 7am we awoke and went straight to the border. We got our stamps, I used my shiny (not really) new fancy visa de objeto determinado, and we found some minibuses headed for La Paz. The Peruvian man was hesitating as to which bus to take, and ended up getting separated from Luz (I now knew her name) and I. The bus got filled to capacity with the 2 of us, several local Bolivians, and some Colombian university students traveling on holiday. Ninety minutes later we made it to the El Alto bus terminal, and I helped Luz get with her 2 large suitcases to the Ralfbus office to claim her waiting ticket for her home country. I wandered over to Avenida 16 de Julio and looked for a taxi. None were passing so I eventually just hopped on another minibus headed for the Prado. We took to the Autopista and I thought perhaps it would all be smooth from there.

But alas, it was late April in La Paz, and in the build up to May Day, the COB was protesting by blockading the main thoroughfare from El Alto to La Paz. So halfway down, the bus had to back up, turn around, travel the wrong way on the highway, make an illegal U turn to go the other way (but still the “wrong” way for that side of the road), and turn off onto a side street. I eventually did make it to the Prado, and went directly to Paceña Salteña for lunch. I sat down to eat at 12:15, 27 hours after I boarded the flight bound for Juliaca. So I saved 3 hours by not taking the bus. And the cost really wasn’t that much more than the bus. But I think, with all I went through, a nice full cama tourist bus for 30 hours would have been preferable. |

themes

All

archives

August 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed