He may be right. In fact, I hope he is. But I think this is precisely the reason starting in a new place for a postdoc is doubly hard.

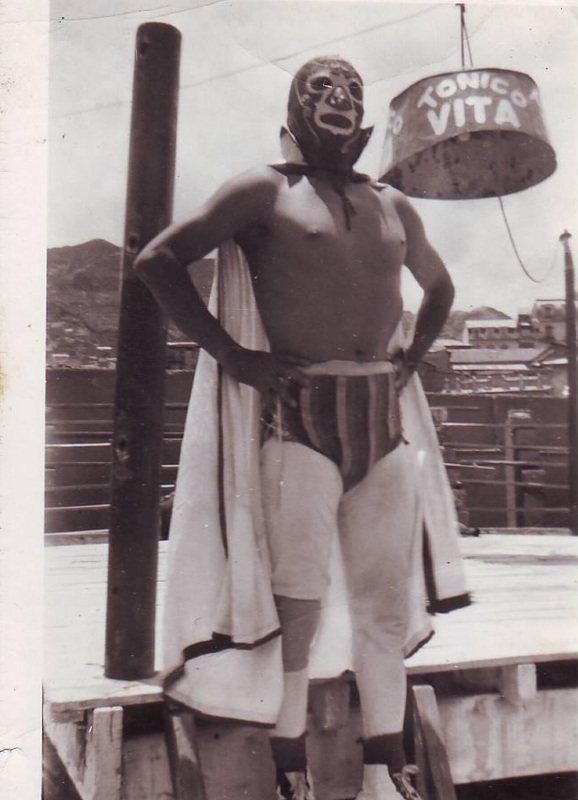

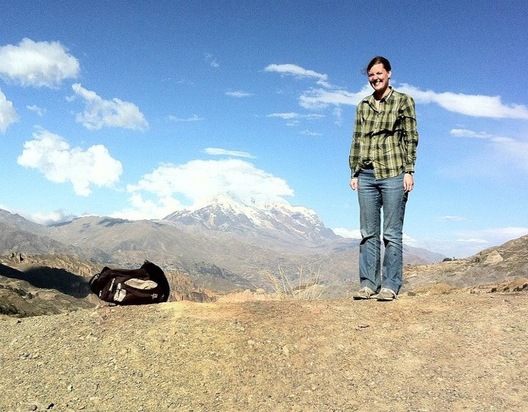

I remember arriving in La Paz the first time. It was the 15th of July, the day before La Paz celebrates their rebellion from the Spanish (not independence, mind you). The streets were empty. I knew no one. I felt lonely. I thought that I would never feel totally comfortable, never quite safe, never out of scrutiny as a gringa. I thought I would never speak Spanish well. I would never understand the bus system. I’d never go out at night alone. I’m not sure if I really believed that or just felt it (probably somewhere in the middle). I didn’t ever take a taxi alone. I would practice what to say before walking into a store or meeting someone new. I took my default research assistant everywhere. I felt like a foreigner.

But my point is not to wax poetic about how much I love Paceños. My point is, I think this makes starting over even harder. When I got to La Paz, I thought, “ok, this is just how it is to be foreign.” But now I know how good it can get. That you don’t always feel like you’re on the outside. That sometimes, you really do feel more like one of them, than those annoying gringoes that just asked directions to the English Pub. And so, I aspire to more now. This is not just a city where I’m doing fieldwork. It is a city where I live. It’s a city where I will do lots of hard work. But it’s also a city where I will have fun. Where I will grow, talk, and watch movies, and eat food, and laugh and cry, and think, and sometimes not think.

So, to be in this initial phase is doubly hard. It is hard, just as any new beginning is, because I am trying to meet people, and develop a routine, and get to know the landscape, and quell fears. But it is also hard because I have higher expectations than ever before. I don’t just want to be here. I want to live here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed